This story contains detailed descriptions of the death of a child.

Detective Eric Matthews decided Jessica Logan probably killed her baby before he talked to a single eyewitness or collected almost any evidence. At that point, on Oct. 9, 2019, the coroner hadn’t yet announced a cause of death. What Matthews did have was a recording of Logan’s 911 call from two days earlier.

The detective scribbled notes as he listened.

“Jessica,” the 911 dispatcher said at one point, “take a deep breath for me, OK?”

“I can’t,” Logan replied, inhaling sharply to force the words out. “That’s my baby.”

“I know. I know.”

“I need my baby.”

The call had come in just after 3 a.m. from a duplex in the heart of Decatur, Illinois. On the tape, Logan struggled to gain her composure as the dispatcher asked what had happened.

“I came in my son room to try to give him a breathing treatment because he needs breathing treatments,” Logan said as she sobbed. “And he’s not breathing.”

She had found her 19-month-old son Jayden tangled up in his bed sheets, face down and stiff, one arm bent above his head and white foam spilling out of his mouth.

“He’s so cold and hard,” Logan said.

“What?”

“He’s so cold and hard.”

Rigor mortis had already begun to set in by the time Jayden’s grandmother and her husband rushed into the apartment. For the final two minutes of the call, Logan could no longer speak. There were only screams.

All of this, the detective concluded after the recording stopped, was an act: The 25-year-old mother of two had likely staged the scene to cover up a murder. He had the evidence right there on tape, and now he was going to build his case against her. Matthews, a veteran on the Decatur police force with buzzed hair and an even temperament, didn’t reach this revelation by applying some tried-and-true police method or proven science.

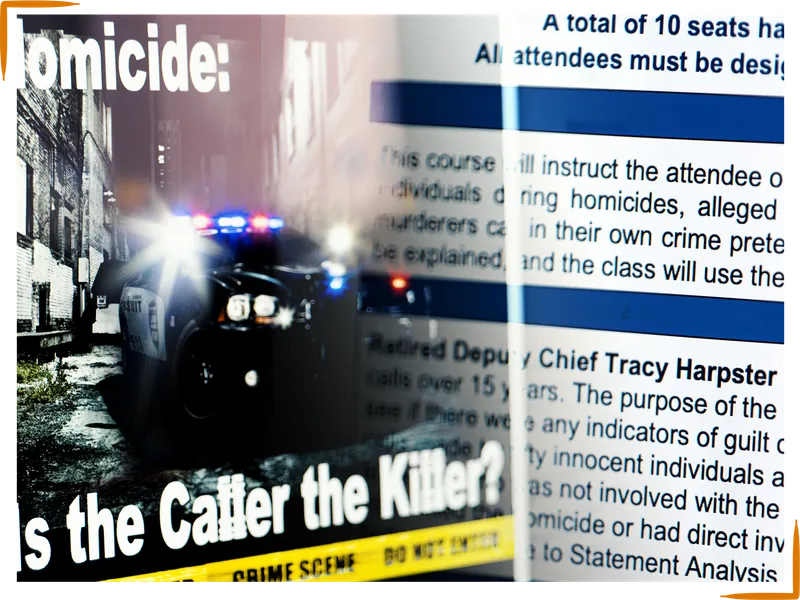

Five months earlier, he had taken a two-day law enforcement training course called “911 homicide: Is the caller the killer?” that was held at a nearby community college. The instructor, who is the chief architect of the discipline, promises those who attend his classes they’ll leave with the power to solve murders by listening to a 911 call.

For more than a decade, the training program and its methods have spread across the country and burrowed deep into the justice system, largely without notice. Pitched exclusively to law enforcement, others in the justice system, including defense lawyers and judges, often learn police have used the technique for the first time in the courtroom.

Today there are hundreds of police officers, prosecutors, coroners and dispatchers nationwide who have taken the course and could now present themselves as experts, able to divine truth and deception — and guilt and innocence — from the word choice, cadence and even grammar of people reporting emergencies.

For Matthews, Logan presented a textbook case on which to apply his newly minted skills. She did not explain precisely what had happened until almost a minute into the 911 call, and she never explicitly asked for an ambulance for Jayden. These, the detective noted in a report, are “indicators of guilt.”

She gave information in an inappropriate order. Some answers were too short. She equivocated. She repeated herself several times with “attempts to convince” the dispatcher of Jayden’s breathing problems. She was more focused on herself than her son: I need my baby instead of I need help for my baby. And when asked if Jayden was beyond any help, Logan said, “I think he’s gone.” She had “already accepted that Jayden was deceased,” Matthews noted in his report.

According to the detective, almost everything Logan said — and didn’t say — was evidence of her guilt.

He documented his findings and then got to work sharing them. His interpretation of her 911 call that day would come to play a profound role at almost every turn of the case that followed, while Logan’s family, already shattered by one unspeakable loss, reckoned with the possibility of another.

Matthews did not respond to multiple interview requests, and the chief of the Decatur Police Department declined to comment or make any of his staff available for an interview. Neither replied to a list of detailed questions.

In the coming weeks, ProPublica will reveal the origins of 911 call analysis and the local, state and federal agencies that foster it, despite a consensus among experts that its application is scientifically baseless. Police and prosecutors continue to leverage this method against unwitting defendants across the country, ProPublica found, in some cases slipping it past judges to present it to jurors.

The case against Jessica Logan — reconstructed here from dozens of interviews, videos and audio recordings, as well as more than 1,000 pages of internal emails, text messages, police reports, court filings and other records — illustrates the fragility of long-established legal protections meant to guard against junk science and its impact on families.

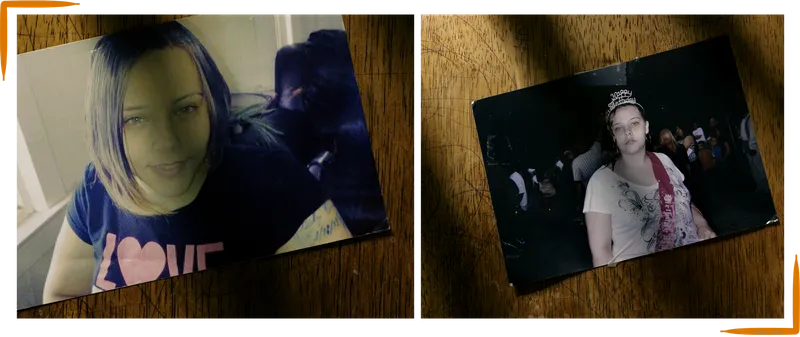

Hope Bradford, a mother of three with eyes that smile before her mouth can catch up, took in Logan, her son’s then-girlfriend, when she was 17. It was an unofficial adoption after Logan’s biological mother died of cancer. She’s called Bradford “Mom” ever since. To Bradford, Logan is “Butterball.” Only Jessica if she’s in trouble: Jessica when she cut class; Jessica when she was arrested for shoplifting as a teenager; Jessica when she got caught joyriding her father's Chevy and showed up at Bradford’s doorstep.

Bradford’s tone, normally buoyant, drops low and icy when she’s meting out discipline to her kids and grandkids. “You’ve got to get your shit together,” she told Logan one time after her new daughter backslid. Like most do when Bradford gives orders, Logan obeyed.

Bradford’s son, Shawneen Comage — father to Logan’s two boys — did not. In October 2018, he was arrested for punching Logan in the face six or seven times, just feet from where Jayden slept, child services records show. He was convicted of domestic battery. Comage had abused her before over the years, his fits of rage memorialized by holes pockmarked in the drywall around his bedroom. In an interview, he said he regrets that part of his past and that he’s come a long way since.

After the episode in 2018, a state child services investigator noted that Logan seemed “somewhat complacent” about Comage’s violence. It’s not far from how friends and family describe her: gentle and guileless, with a placid affect that can be difficult to read. Her narrow green eyes often stare vacantly. As a child, she was diagnosed with a learning disability so severe that she qualified for government benefits after graduating high school. She needed the questions on her final exams read to her.

When Logan speaks, she takes long pauses to think over an answer, and the words fall out of her mouth slowly. She drags vowels. She repeats herself often. “It’s like she’d be in a daze about certain things,” one relative observed. “I don’t want to say Jess is slow,” another said affectionately before trailing off.

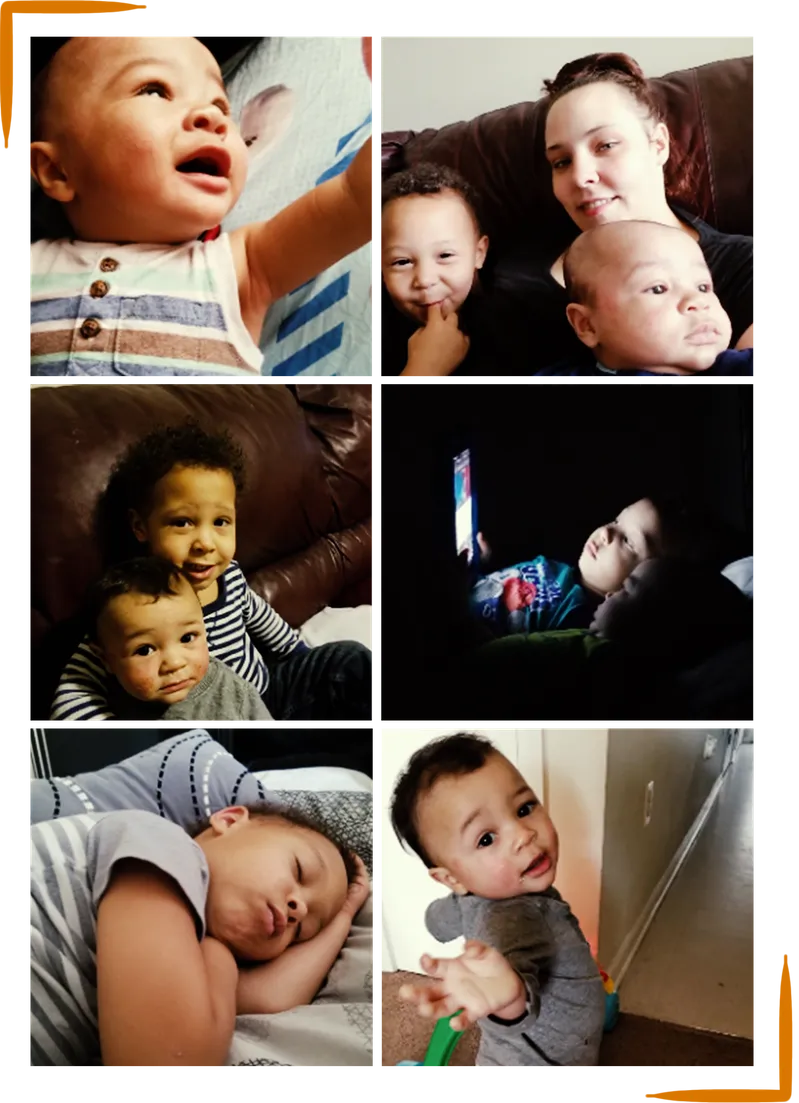

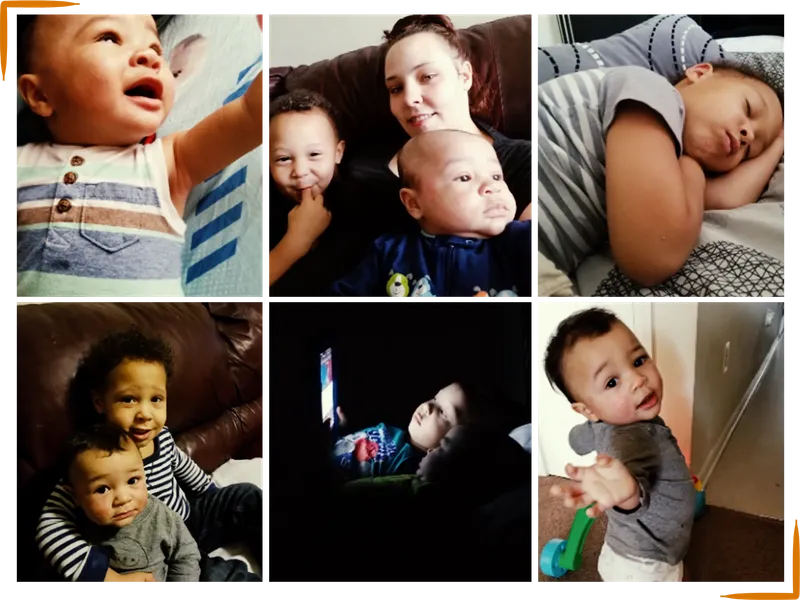

Logan turned 22 and moved into her own apartment, the first that felt like a real home after brief stints in two other places. It was a Section 8 duplex with white vinyl siding minutes away from Bradford. Logan loved the clean carpets and playground right outside where she could snap pictures of Jayden and her older son Je’Shawn playing together. She recorded hundreds of such moments — the mundane and the milestones: first steps, spaghetti dinners, birthday parties, even trips to the doctor.

Logan felt independent. She started to plan a future for her family, maybe somewhere down south. She researched U-Haul prices and affordable housing options. “My goal,” she said later, “was to have three kids and own my own house before the age of 30.”

But the bills piled up quickly. She tried to keep her head above water with odd jobs and babysitting gigs, relying largely on food stamps and whatever she could borrow from family and payday loan companies. More than once, she overdrafted her checking account to buy gas and diapers. Bradford, a certified nursing assistant, eventually helped her land a full-time job in the kitchen at a nearby long-term care facility.

On the afternoon of Oct. 6, 2019, Bradford picked up Logan and the boys and drove to Walmart. Jayden — who had grown thickset, with curly black hair and a pigeon-toed waddle — needed new socks and sippy cups. Just socks for Je’Shawn. Logan had $20 in her pocket and nothing in the bank as she pushed Jayden in the shopping cart.

Bradford told Logan, “You need to get some new underwear, Butterball,” something she had discovered after finding tattered panties in the laundry. But the $20 was just enough to cover the boys. At checkout, Bradford paid for the underwear and then dropped all three back home.

Hours later, just after 3 a.m., Bradford’s phone rang. On the other end, Logan wailed. Jayden or Je’Shawn — Bradford couldn’t make out which one — wasn’t breathing. She told Logan to hang up and call 911.

Bradford and her then-husband, Clint Taylor, sped to the duplex, through red lights, in less than two minutes. Taylor jumped out before the car stopped rolling and bolted inside, where he found Logan talking to the 911 dispatcher and cradling Jayden’s body.

When Bradford came into the living room, both women began to scream. Taylor scooped Je’Shawn up and carried him outside toward the flashing lights that had arrived on the scene. Firefighters rushed in, but it was too late.

When the coroner took Jayden’s body away, “I observed Jessica to be very upset and crying,” a patrol officer wrote in his report. “After giving her time to calm down, I conducted an interview.”

When a child dies, families are tormented by what they don’t know. Sometimes babies and toddlers just stop breathing in their sleep, from accidental asphyxiation, illness or a maddeningly unclear combination. In 2019, at least 125 children Jayden’s age died of “undetermined causes” in the U.S., according to government estimates, a phenomenon known as Sudden Unexplained Death in Childhood. More than 200 were killed in homicides.

There often appears to be little way of distinguishing between the two explanations. Absent definitive physical evidence, police may try to fill the gap with circumstantial clues, assigning meaning to how family members behaved before and after. The grieving parent becomes a suspect.

Once they decide a death is a homicide, detectives have an array of tools at their disposal. For decades, law enforcement has repeatedly embraced the latest evidence to fall under the banner of “forensics.” Bite marks, hair follicles, roadside drug tests, written statements, polygraphs and blood spatter have all been analyzed with techniques that were later called into question.

Still, some prosecutors have accepted this evidence as fact before they leverage it in plea deals or judges allow them to present it to juries. At least 416 people nationwide have been exonerated since 2012 after they were convicted with faulty forensics or misleading expert testimony, according to data from the National Registry of Exonerations, a project from three universities.

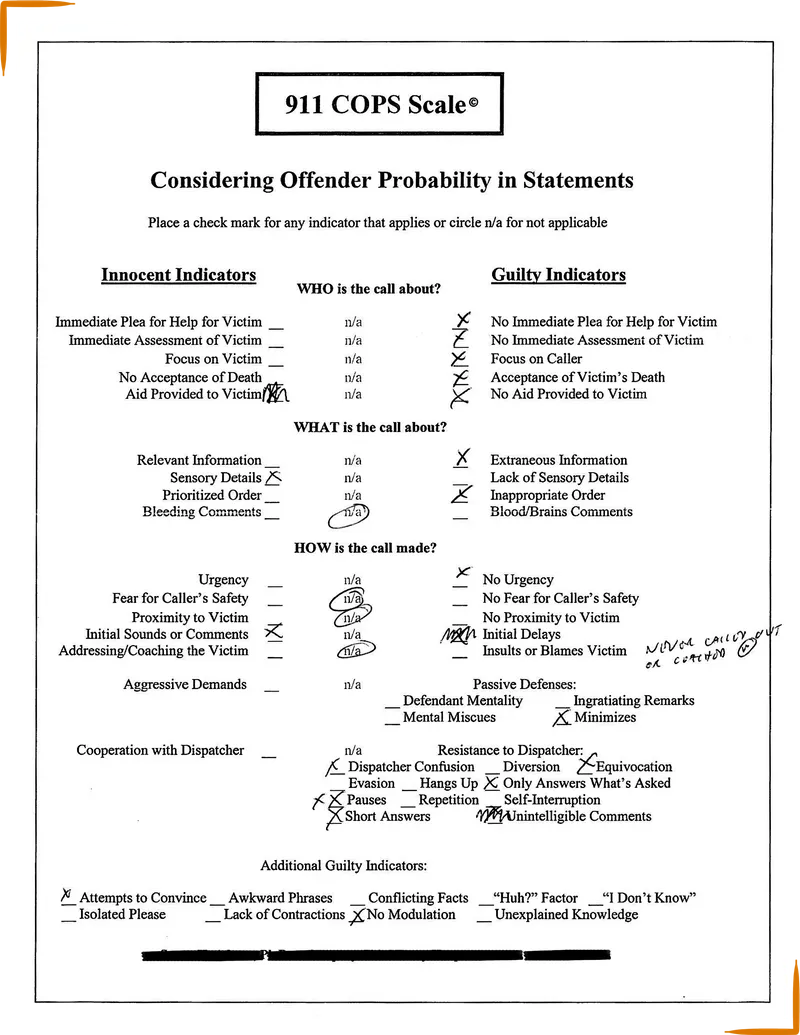

Similarly, 911 call analysis is a measure of law enforcement’s credulity, favored in cases with few witnesses or other evidence to differentiate an accident from a murder. Use of this method is still a well-kept secret among police and prosecutors, who almost never share their analyses publicly. In emails with one another, however, they extol its value in solving murders and frequently consult with the program’s chief architect, a retired deputy police chief from suburban Ohio named Tracy Harpster.

Emergency 911 calls are, without doubt, critical pieces of information for investigators. They often establish a raw first-hand account and timeline that can later be checked against other evidence. But Harpster preaches they are also much more: The recordings are ciphers that can be decoded to help solve murders, if, and only if, you take his training course. He gets paid up to $3,500 to teach an eight-hour class.

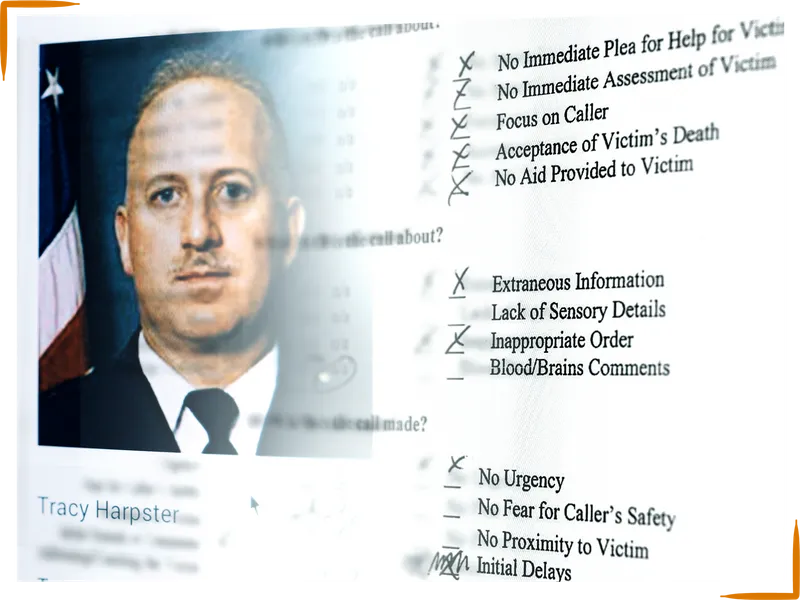

One in three callers reporting a death, Harpster claims, betray their true involvement with unconscious word choices, omissions and patterns of speech — what the program calls “indicators of guilt.” For instance, “Huh?” in response to a dispatcher’s question is a guilty indicator. So is an isolated “please.” Other indicators are more subtle and subjective: Did the caller provide “extraneous information”? Was there too little urgency in their tone? Too many Freudian slips or other “mental miscues”?

Those who take the training are given a simple checklist to track how many of these errors a caller commits. Harpster first began developing the list as a criminal justice graduate student. For his master's thesis in 2006, he listened to 100 recordings and claimed that certain indicators correlate with a caller's guilt, and others with innocence.

Today, Harpster tells students they can use the model — which he and two coauthors later expanded on in a peer-reviewed exploratory study — to predict a 911 caller’s role and help solve murders. If there are enough guilty indicators, he often says, then the call is “dirty."

Twenty researchers from seven federal government agencies, universities and advocacy groups have tested Harpster’s model against other samples of 911 calls to see if the guilty indicators he had identified did, in fact, correlate with guilt. They’ve consistently found no such relationship for most of the indicators. In two separate studies, experts at the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit warned law enforcement officials to exercise caution when using 911 call analysis because their results contradicted so many of Harpster’s claims.

Given the popularity of the training course, one researcher told ProPublica, “we had to make sure it could be replicated — and it couldn’t.”

Patrick Markey, a psychologist at Villanova University who has been studying 911 calls, added that he’d find it “very disturbing” if Harpster’s method were being used to help convict people. “We don’t know if it’s valid or not,” Markey said.

In an interview last summer, Harpster defended his program and noted that he has also helped defense attorneys argue for suspects’ innocence. He maintained that critics don’t understand the research or how to appropriately use it, a position he has repeated in correspondence with law enforcement officials for years. “The research is designed to find the truth wherever it goes,” Harpster said. “I’m pro-police but I’m not pro-bullshit.”

He would not allow ProPublica to sit in on one of his training sessions and declined subsequent interview requests. He also did not respond to a detailed list of questions about his method’s role in Logan’s case.

Susan Adams, a retired FBI agent and one of Harpster’s coauthors, said in an email that they analyzed 300 calls for their study and a book on the subject. They’ve also volunteered their time to help police and prosecutors on many other cases. (Harpster claims he has directly assisted in more than 1,000 homicide investigations.) No single indicator can be used to determine the likelihood of innocence or guilt, Adams said. “Instead, our study examined indicators in combination, just as 911 call analysis should be used in combination with case facts to uncover the truth.”

Psychologists and criminal justice experts say applying the model in the real world is dangerous because those indicators can indicate very little; that such judgments often amount to reading tea leaves; that it’s extremely difficult to decide what someone should or shouldn’t say in an emergency because everyone reacts differently; and that parents holding their dead children may very well speak irrationally.

“You might as well flip a coin,” said Maria Hartwig, a psychologist and professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice with expertise in deception detection. Hartwig and others said that a commercial operation selling 911 call analysis should be met with skepticism instead of credence.

This did not happen when Matthews took the course in Decatur. Records show that local and state officials readily certified and funded Harpster’s program with taxpayer dollars.

Matthews’ class was held at Richland Community College, a low brick complex on the far side of Decatur, an agroindustrial city in the center of Illinois. Decatur is scarred by train tracks and surrounded by corn and soybean fields. On a typical day, student drivers in a tractor-trailer navigate orange cones in the school’s parking lot.

Over the years, the Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board has approved Harpster’s program for credits toward a lead homicide investigator’s certificate, often funding the class with state grants. As the name suggests, the board is supposed to set statewide training standards.

When approached by ProPublica, the board could provide no record that it had scrutinized the research behind the curriculum. John Keigher, the board’s chief legal counsel, said he was unsure how the previous training manager had vetted Harpster’s application. “Maybe he did his own research and Googled stuff,” Keigher said.

Keigher had no misgivings about the program and said that local training agencies, which are partly funded by the board, get to choose who they host.

In Decatur, that entity is called the Law Enforcement Training Advisory Commission, which also provided no record of evaluating the validity of the course before offering it to local police and prosecutors.

Approval from these outside agencies lent Harpster’s class unqualified legitimacy. To small departments that may be less equipped to judge new techniques on their own, the method appears groundbreaking. Or, as one former attendee wrote in the commission’s course evaluation form: “One of the best if not the best course I’ve taken in 21 years of law enforcement.”

Five months after he took the 911 call analysis training, Matthews put his new skills to the test on Logan’s call the day he was assigned the case. Emails indicate that he asked Harpster for a consultation on the case. It was at that moment that Logan became a suspect.

After he analyzed the call, Matthews spoke with the patrol officer who had first interviewed Logan at the scene. That officer then filed a new report “in light of recent discoveries.”

In the second report, he wrote that Logan’s emotions were insincere; there were no actual tears in her eyes; and she was silent sometimes but hysterical at others. “I originally believed this was possibly due to the shocking and traumatic experience,” the officer said, “but the crying somehow did not seem genuine and felt forced.” (He later explained in court that he normally chooses to report only facts to preserve the integrity of the investigation, but after learning the new information from Matthews, the officer wanted to put his opinion about Logan’s demeanor into the record as well.)

Matthews also testified at the coroner’s inquest — a hearing separate from criminal proceedings where the coroner presents an autopsy report and other evidence to a panel of jurors, who then determine the official manner of death. Matthews told the jurors he was trained in basic and advanced 911 call analysis and said he found “mostly all guilty indicators” in Logan’s recording.

At one point early in the investigation, Matthews told a child services investigator that he had identified red flags in the case, according to meeting notes of the conversation. The detective explained that Logan “had failed the 911 stress test,” citing the fact that she repeated several times that Jayden suffered from breathing problems, as if to establish an alibi.

Jayden did have a history of respiratory illness. Medical records show his mother took him to the hospital or doctor’s office more than two dozen times after he was born, the final time a month before he died, when he had a fever, cough and rash. “I just be so paranoid and scared,” Logan told Matthews once. Jayden had been diagnosed with respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, and treated for bronchiolitis and viral pneumonia at different points in 2018. He was admitted at least four times. Doctors prescribed him breathing medication to be administered through a nebulizer. He was sick, it seemed, more than he wasn’t.

At Jayden’s funeral, Je’Shawn, who turned 4 that same week, looked inside the casket, touched his little brother’s face and asked his mother to fill Jayden’s sippy cup. Jayden was buried next to three cousins, each of whom had been born months premature before dying in the hospital. All four names are tattooed on Bradford’s wrists.

For days, condolence messages poured in from friends and relatives checking on Logan. She deactivated her Facebook profile and ignored many of the texts, replying only in quick bursts to others:

Trying to keep it together

Can’t stop crying

I haven't slept or really ate in 2 days

Just trying stay strong for Je’Shawn

He keep asking for his brother.

The coroner hired Dr. Scott Denton, a forensic pathologist, to perform the autopsy and determine a cause of death. After his preliminary review, Denton asked Matthews to enlist Logan for a video reenactment of the night Jayden died. Logan said she didn’t feel like she had a choice and returned to the duplex with Bradford, but without a lawyer, on Oct. 17. Matthews told Bradford to wait outside.

With the camera rolling, Logan stood in Jayden’s bedroom and held a Jayden-sized mannequin. She placed it on top of the Paw Patrol bed sheets, which were still where she’d left them weeks earlier, and gave her account of the crucial hours between Walmart and the 911 call.

Logan said she had followed the nightly routine: baths at 7:30, playtime and television for an hour and then off to bed. She put Jayden down in the bottom bunk. “I gave him a kiss good night and told him I loved him,” she said. Je’Shawn slept in her bed.

Before she climbed in next to Je’Shawn around 10:30, she peeked at Jayden, who had been fighting a cold, and then set two phone alarms, one for midnight and one for 3 a.m., to administer the breathing medication. She slept through the first alarm. (Days before, she had Googled “what does it mean when you sleep really heavy and can’t hear nothing,” according to her search history.) Then, she said, she woke at 3 a.m. before padding across the hall into Jayden’s room.

Logan found him face down with the fitted sheet wrapped around his head. His bare back was cold and his arms stiff. Just like her biological mother had felt to her on her deathbed 10 years earlier. “I knew,” Logan told Matthews, “that he was already gone.”

In his report, Matthews echoed several of his observations from the 911 call analysis: “Jessica did not appear to be upset or troubled when manipulating the mannequin and illustrating how she discovered her deceased son in his bed.” Before leaving the house, the detective asked for Logan’s cell phone. She handed it over.

A week later, Matthews invited Logan to the police station to talk again. A relative drove her downtown. Je’Shawn, his cousin and another friend rode in the back seat. “I’ll be right back,” Logan told them. The detective led her into a small, white room, where a white chair was waiting for each of them.

Matthews pushed his chair back from a desk and turned to face Logan, their knees inches apart. “I’m running into a lot of problems with this, your account of what happened,” he said. “I’m finding problems from the moment you called 911 until today.”

Matthews, who has been a juvenile detective for years, spoke obliquely at first. Her story didn’t add up, he said, and the professionals agreed with him; she wasn’t a monster, but a young, desperate mother at the end of her rope. As his words rushed at her, Logan hardly moved. Matthews alluded to something incriminating on her phone but didn’t elaborate. (Records show police had discovered evidence of a Google search, apparently from the day before Jayden died, for the phrase “How do you suffocate.”)

“There’s irrefutable proof that something happened to this kid and that you did something to him. OK?” Matthews said. “You killed Jayden.” At that, she shook her head back and forth: “No, I did not. No, I did not.”

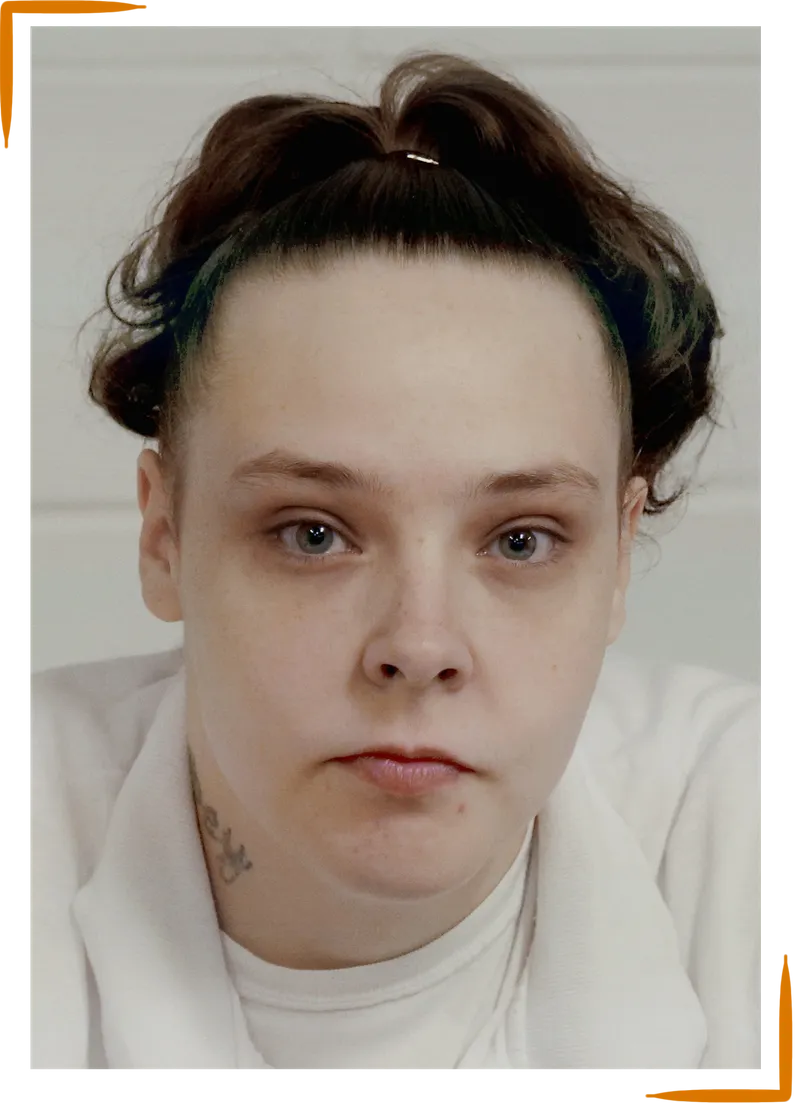

“I’m going to be able to prove it,” the detective said. He told her that during one of their earlier interactions she “had no emotion at all.” In his report later, Matthews wrote that Logan remained “generally emotionless,” with her hands in her pockets and little visible reaction. That inscrutable countenance again.

“Everybody shows their emotions different,” she told him.

When Logan asked for a lawyer, the detective said she was going to be arrested for murdering Jayden and stood to leave. For almost an hour, she waited in the white room alone, hardly moving except for a tapping right foot. She was so still, the motion-sensitive lights turned off. She sat in darkness.

In the parking lot outside, Je’Shawn played in the back seat of the car. His entire immediate family had now vanished — both parents behind bars and his only brother dead.

Almost two weeks later, Je’Shawn climbed on top of a large leather chair in a child services center in downtown Decatur. He sat across from a female staffer. Between them was an easel. She said she wanted to ask him some questions about his family while they drew pictures together.

“Who all do you live with?” the woman, cross-legged on the floor, asked gently. Je’Shawn fidgeted with toys and explored the room. He said he lived with his grandma now. She drew a house with two smiley faces inside.

“My brother not there,” Je’Shawn offered.

“How come your brother’s not there?”

“Because he’s in heaven.”

The staffer tried to get details about the night Jayden died and what Je’Shawn may have seen. He mentioned a cover over his brother’s face but little else that tracked. (“I farted,” he confessed at one point.)

After a few more rounds, she left Je’Shawn in the room by himself for a moment. He picked up a toy cellphone and flipped it open. “Hi, Mama,” he whispered into the receiver. “I’ll draw you a picture.”

He pressed the marker against a new sheet of paper and drew his brother.

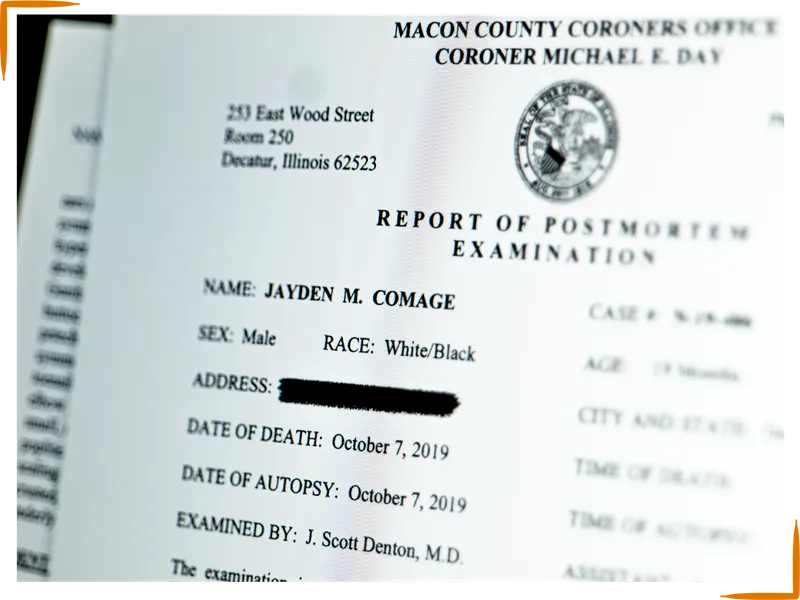

After Logan was arrested, Denton submitted his final report. Cause of death, the pathologist wrote, was asphyxia by “smothering and compression of the neck.” The coroner’s inquest made it official: homicide.

ProPublica consulted with three forensic pathologists who had no prior knowledge of Jayden’s case to review the coroner’s files, including the autopsy report, photographs, medical records and reenactment video. None of them accepted Denton’s conclusion of smothering, which, they said, is tantamount to declaring homicide. They noted that deaths by asphyxia are often accidents or due to illness. (Denton did not respond to multiple interview requests, and the coroner who had hired him declined to comment for this article. Neither replied to a detailed list of questions.)

Dr. Shaku Teas, a forensic pathologist who performed more than 600 autopsies on children during her nearly two decades at medical examiners’ and coroners’ offices across Illinois, said she could see no trauma to Jayden’s body. “There’s going to be some trauma when you suffocate a 19-month-old,” she said, because of their size coupled with an instinct to resist. “I don’t know where he came up with a homicide.”

In the autopsy report, Denton identified light blanching on the tip of Jayden’s nose and tiny dots on his eyelids, cheeks and elsewhere — burst blood vessels called petechiae. Teas and the other pathologists said Denton’s interpretation of the dots was overstated. Much of it looked like it could be a rash, they said.

Two preeminent pathology experts wrote in a 2000 paper that petechiae dots around the face and eyes, by themselves, “point to no particular cause of death” because they can also appear during moments of physical exertion like coughing, sneezing or respiratory distress. Misattributing these dots, the authors wrote, can lay “false grounds for conviction.”

Dr. Jane Turner, a private consultant and former medical examiner in St. Louis, told ProPublica the petechiae and blanching on Jayden could be explained by accidentally suffocating face down or a seizure. She said Denton didn't seem to test for respiratory viruses or test Jayden’s cerebral spinal fluid — grave errors given his medical history. “The cause of death and manner of death should have been undetermined,” Turner said. “There were gaps in the investigation with respect to the autopsy and some questionable conclusions.”

After Bradford attended the inquest and learned the results of Denton’s autopsy report, she realized Logan’s case would likely go to trial. Logan called her that day from jail. They cried as they spoke. “I’m sick to my stomach right now,” Bradford said. “I just cannot believe this.” Je’Shawn played in the background.

Logan told Bradford she was feeling so depressed that she planned to see a mental health counselor. “J.J. was a sweet innocent boy,” she said, using Jayden’s nickname.

“I would never,” Logan added, her voice catching.

“I know you wouldn’t,” Bradford said before it was time to hang up. “I love you, Butterball."

Logan’s trial took three days in June 2021. Nineteen months had passed since she was arrested. She sat in court, hands laced together, next to Christopher Amero, a local lawyer and military veteran with a thick, red beard. Logan’s family pooled their money to pay him $10,000.

The state’s lead prosecutor laid out his narrative to the jury several times: Logan was drowning in debt, so she murdered Jayden to cash out his $25,000 life insurance policy. Police found no vials of the breathing treatments, he said, evidence that she never intended to give them to Jayden. The jury heard a barrage of voicemails from debt collectors and prison phone conversations. In some of the recordings, Logan snapped at Je’Shawn for misbehaving. In others, she told her children's father how far behind she’d fallen on the bills.

Logan’s plan, the prosecutor said during his opening statement, was to smother Jayden in the middle of the night and call 911 a few hours later with a manufactured story about breathing problems. “That plan betrayed her,” he added. “Forensic science betrayed her.”

He played the six-minute 911 recording before calling Matthews to testify. The prosecutors had been wary of introducing Matthews as an expert in 911 call analysis, emails indicate, and resolved to instead incorporate the guilty indicators subtly during closing arguments. It’s a common legal tactic to circumvent courts’ standards for expert testimony.

“She’s 45 seconds into the 911 phone call before she even says, ‘My child’s not breathing, and I need help,’” the prosecutor told the jury. “A mother telling you that there was no reason to try to see if her 18-month-old could be saved. Does that sound right to you?” The Macon County prosecutors who tried the case did not respond to interview requests or a list of questions about how they used 911 call analysis.

But Amero served the prosecution an unexpected boon during cross examination: He asked Matthews specifically about the “multiple indicators of guilt,” which the detective had detailed in a sworn statement, along with other observations about Logan’s suspicious demeanor. Matthews seized on the moment, explaining the research and how he had first determined that Logan was a suspect.

“In this training,” he said, “we use a chart that will allow you to determine whether the person was being honest on the call or not.” Matthews testified that Logan never once explicitly asked for help during the 911 call and a full minute had elapsed before she explained what was going on.

Amero later told ProPublica he thought that the combination of the 911 recording and Matthews’ analysis was a turning point in the trial.

The prosecution’s most important piece of evidence against Logan was Denton’s testimony about his autopsy. Amero did not call another pathologist to puncture Denton’s conclusions. The jury was left to believe that the only way Jayden could have the tiny marks and light blanching on his face was if he’d been smothered.

Another critical piece of evidence was an item that police had discovered on Logan’s phone: a Google search for the phrase How do you suffocate. The police report is unclear, and an officer wrote that he found the search in some of the phone records but not others. In court, that officer testified the search took place 19 hours before Jayden died, which he had verified with a subpoena to Google. This, prosecutors said, was proof she had planned to kill Jayden. ProPublica reviewed a search history file from Google but was unable to independently verify the police department’s analysis of the data extraction.

The family disputes the timeline. After Jayden died, relatives gathered at Bradford’s house to grieve. Bradford’s biological daughter asked if Jayden could have suffocated. According to Logan and Bradford, that’s when Logan searched for How do you suffocate. (Bradford’s daughter and Taylor said they saw Logan on her phone at that moment but did not see what she typed.)

Then there was the life insurance agent who said Logan had called the day after Jayden died to inquire about his policy. The agent found the call suspicious enough to tell police. The family maintains this is also a misunderstanding. The morning after Jayden died, those at Bradford’s house discussed paying for the funeral and travel for Jayden’s father to attend.

A family friend came over with sandwiches. She overheard the conversation and suggested calling the insurance company to ask about Jayden’s policy. Then Logan made the call, according to Bradford, Logan and Taylor. “That was my fault,” the family friend told ProPublica. “That was all me.” Logan never cashed out the policy. The package the insurance company sent sat unopened atop her dresser until after she was arrested.

Police never interviewed the family friend, and Amero didn’t call her to testify. He didn’t call any character witnesses besides Bradford — a decision that incensed the family as the trial wore on. Logan’s father, Joey Logan, and her sister Brittany Phipps sat next to one another in the gallery. Phipps said the judge threw her out of the courtroom for groaning and glowering. Bradford didn’t trust herself not to do much the same and sat alone in an anteroom for most of the trial.

After an initial interview with ProPublica, Amero did not respond to requests for comment or questions about his strategy at trial.

Joey Logan, a sandblaster with a bum eye who keeps a pack of Marlboro menthols stationed in his front shirt pocket, never got the chance to tell the jury how much his daughter doted over her sons.

“Jess would do anything for them boys,” Logan said in a recent interview. “She did everything for them boys.”

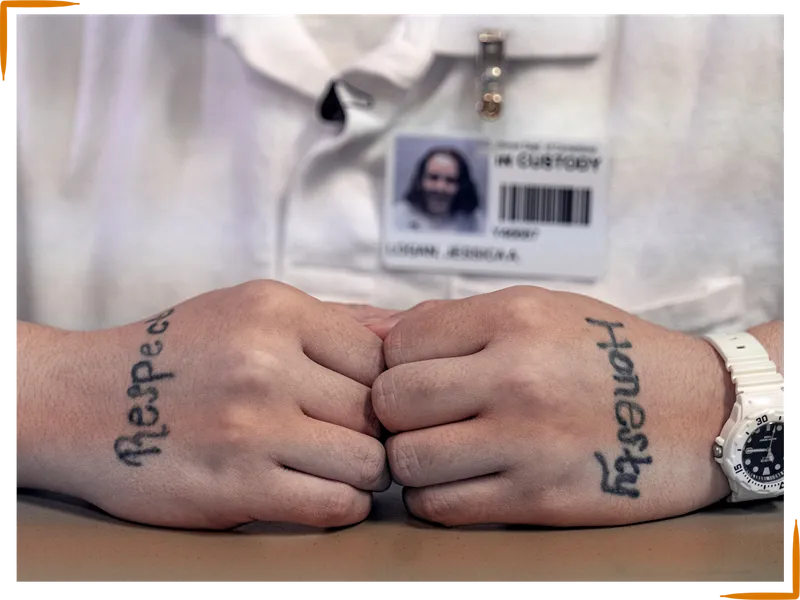

On the last day of the trial, Jessica Logan took the stand. Tattooed on her left hand, in bold letters, was the word “honesty.” She described her relationship with her boys’ father; her earlier miscarriages; the learning disabilities that slowed her down in school; her unsuccessful attempt to earn a degree from the community college; one of her jobs, at a takeout chicken restaurant in town; the two dozen doctors’ visits for Jayden. And she told her version of what happened the night he died.

Logan said she was proud of the fact that she was paying for Jayden’s life insurance and seemed confused when asked why she never cashed out the policy. “It wasn’t going to bring my son back,” she said.

In his closing arguments, the lead prosecutor warned the jury not to infantilize Logan or excuse what she’d done because she’s “not very bright.” The trial, he said, was about Jayden, “a boy who wasn’t able to protect himself from the world.” He said that was Logan’s job, “and she was the person who killed him.”

Amero pointed out that Matthews never tested the bedding for Jayden’s lung fluid. “Why was it never done? Because Detective Matthews listened to the 911 call, on the same day that he got assigned the case,” Amero said. “Because she wasn’t being emotional enough.”

In a breathless rebuttal, Amero pleaded with the jury to reconcile the 911 recording they heard, the analysis offered by Matthews and their own common sense. “It almost took a minute before she was able to get anything out to the dispatcher,” he said. “Why did it take her almost a minute? Because she couldn’t gather herself. Okay. That’s why it took a minute.”

“Every one of you heard the 911 call,” Amero continued. “If that call was not a plea for help, then I cannot explain to you what is. That entire call was a plea for help. But because she didn’t, specifically, say, ‘Please come help me,’ we’re going to use that as an indicator of her guilt. Is that justice? Is that logical? It’s not.”

The jurors deliberated for less than two hours before announcing their decision: guilty of first-degree murder. Logan’s chest got heavy, as she put it later, and the dam burst. She sobbed. A local television news reporter covering the trial criticized her for being conspicuously impassive throughout the trial. “But when that guilty verdict came down,” the reporter said, “tears started to stream down her face.”

At the sentencing in July, Logan asked the judge for leniency. “It hurt me to know people think I — think I did this based off of my emotions,” she told him. “Everyone grieve different.” The judge sentenced her to 33 years.

Connie Moon, a retired schoolteacher with lightning white hair, was one of the jurors at the trial. In a recent interview, she said she was persuaded by the financial motive laid out by the prosecutors. “It’s one of those sad stories about poor, desperate people,” Moon said. “But I do stand by my verdict.”

A second juror, who asked to remain anonymous so she could speak freely, told ProPublica she found Logan’s 911 call odd, an opinion validated by Matthews’ testimony at trial. But, more than anything, she was convinced by the autopsy report and Denton’s description of the findings. Because that testimony went unchallenged, the juror was under the mistaken impression that those small dots and blanching were proof positive of smothering. ProPublica shared with her the conclusions from the outside pathologists.

“I’m part of the group that put her away for 33 years. And that’s a heavy weight. I don’t take that lightly,” the juror said, in tears. “I don’t want her to suffer because we didn’t have the right information. And, I don’t know, maybe we made a mistake in our judgment. I don’t know. I felt at peace at the time. I can’t say I do right now.”

Another juror, who also requested anonymity, went much further. She put little stock into the 911 call analysis because, she said, there are too many differences in the way people speak for anyone to claim an expertise. But she believes now and she believed then: Jayden’s death was an accident, perhaps because Logan tried to settle him in too tightly in the bed.

“They kept saying it was intentional,” the juror told ProPublica, “but I honestly don’t think it was intentional.” The judge explicitly instructed the jurors that they should only vote to convict if they believed that the state proved both that Logan killed Jayden and she had intended to do it or, at the least, meant to cause him great bodily harm.

Still, the juror voted to convict Logan of first-degree murder, which is a deliberate act. She seemed to misunderstand the judge’s instructions. “She didn't murder him. That's the wrong word,” the juror said. “But what do I know?”

The night the jury’s guilty verdict was read, Matthews finished the case where it had started. He wrote an email to Harpster, the chief architect of 911 call analysis. “Just wanted to reach out to you and thank you for your help in my 2019 murder case,” he wrote, including a link to the television news story. Matthews said that he noticed the jury seemed compelled by his testimony and stared intently while nodding their heads. “I strongly believe,” Matthews finished, “that the 911 call analysis was a tremendous benefit to both my investigation and the trial.”

It was just before 6 a.m. on a Wednesday in late August when Bradford walked out of a retirement community center in navy scrubs after her shift ended. The sky over Decatur went from black to blue as she drove across town to the babysitter’s house to pick up her grandson. On Bradford’s mind was a court hearing slated for the afternoon. After more than a year, Logan’s appeal had entered its final stage, and lawyers for both sides would make arguments in front of a panel of judges.

For weeks, Bradford, a devout Baptist, had been anxious about the date and prayed on it nightly. But, as she drove, she felt at peace with whatever the outcome: an immediate ruling from the judges or more months of uncertainty. “I’m leaving it up to God,” she said, turning into the sitter’s driveway.

Two honks of the horn and Je’Shawn bounded outside, a Jurassic World backpack strapped around his shoulders and some loose jelly beans in his pocket. Bradford is in the process of formally adopting Je’Shawn, who has been in her custody as a foster son since his mother was arrested. “He knows that I’m still grandma and he knows who his mom is,” Bradford said once. “He’s never going to forget that.”

Back at the house, as his grandmother clipped his fingernails, Je’Shawn pointed out some of her gray hairs and asked where they came from. “You gave them to me,” Bradford responded with a smile. In the years since Je’Shawn’s brother died, doctors diagnosed him with an anxiety disorder and ADHD. He sees a counselor weekly. He chews his T-shirt collars until they fall apart. He frequently grimaces and blinks with his whole face. He likes Bradford to hold his hand until he falls asleep.

At 7 a.m., after breakfast, Je’Shawn boarded the school bus. Next came Bradford’s daily ritual, an hour of near silence she steals each morning. She sat in a lawn chair on the front porch, next to Je’Shawn’s bike, while the sun rose over the train tracks, through the trees, and splashed her face.

Later that same morning, 45 minutes away past miles of farmland, Logan shuffled into a recreation room at the state’s largest women’s prison. She carried with her sketches of Je’Shawn and Jayden, artwork gifted by another inmate.

It would be Je’Shawn’s seventh birthday soon, and she would get to choose a gift from a prison catalog to mail him. They would eat ice cream and play board games together in the prison’s visitation room.

That also meant it was the anniversary of Jayden’s death. The family would visit his grave without her. Logan has been diagnosed with depression, and she’s been in and out of protective custody because of issues with other inmates, including being the target of frequent bullying. Some call her “baby killer.”

In the rec room, she talked about her case, the appeal hearing later that afternoon and her two sons. She twice retold the story of the night Jayden died. Her eyes welled up, and her voice broke. She blamed herself for not waking up for the first alarm at midnight to administer Jayden’s breathing treatment. That, she said, could have saved him.

Logan has been inconsistent about whether she had preloaded the nebulizer before she went to bed or if she planned to load it after waking up Jayden. There is no mention in the police or court record of any officers checking the actual machine for the medicine, and they didn’t find full or empty vials elsewhere in the house. Logan has also waffled on whether she gave Jayden CPR the night he died.

As she spoke, Logan often stammered and took several beats to connect thoughts. “I have a learning disability,” she explained. “So I can’t really, I don’t really understand a lot of things.” Unlike Bradford, who keeps her frustration close to the surface, Logan said she tends to bury painful emotions. She’s more like her father that way.

“You shouldn’t feel like somebody’s guilty just because the way their emotions is. Everybody react and have emotions different than everybody else,” she said, a refrain she’s repeated since she was first arrested. “I mean there really nothing I could have said differently or did differently. I shouldn't had to reword stuff to make it, I guess, to make Detective Matthews — I feel like I did nothing wrong on the 911 call.”

An hour later, Bradford settled in front of her computer to watch the appeal hearing on a video conference — the fate of her family decided by strangers on the screen. She hunched forward, looking over the top of her glasses to text updates to family. As usual, most of the curtains were drawn, and the house dim. Bradford likes privacy.

Logan’s state-appointed appeals lawyer told the panel of judges that his client deserved a new trial because the first one was unfair for a number of crucial reasons. First, he argued, the reenactment video should never have been admitted into evidence because Logan was not read her rights before she took part in it; and the video inappropriately influenced the pathologist who prepared the autopsy report. An appellate prosecutor responded that the reenactment’s significance was being overblown.

Logan’s appellate attorney said another critical problem with the trial was that Amero had chosen to elicit testimony about the 911 call analysis from Matthews. It was a “grossly unreasonable” gambit, the attorney said, one that allowed the detective to interpret Logan’s credibility. “And that’s the province of the jury.”

Then the hearing ended without ceremony. Everyone’s screens went black, and Bradford stared for a moment. She thought prosecutors continued to dismiss crucial facts in their portrait of Logan, treatment she considered especially glib given the circumstances. “They don’t realize it’s this girl’s life they’re playing with,” Bradford said.

A month later, Bradford got word while waiting in the hallway during one of Je’Shawn’s therapy appointments: Logan lost the appeal. Her attorney has asked the Supreme Court of Illinois to take the case. If the court agrees, it could take another year or longer of briefs and arguments. In the meantime, Bradford plans to move to Texas to be closer to her biological daughter and grandchildren. Je’Shawn will go with her.

After the appointment, Bradford drove back to the house in the heart of Decatur, still her family’s home for now. Inside, on almost every flat surface, are candles, more than 200 of them. She collects the classic fresh linen and vanilla scents, along with the more exotic: names like pumpkin pecan waffles and clementine sherbet. At least one is always burning, giving the house a different sweet smell every day.

In the corner of the living room, propping up a card of inscriptions and prayers from the staff at Jayden’s daycare, is a memorial candle for Jayden, encased in plastic with his picture on all four sides.

Je’Shawn often asks Bradford to light it.

No, she tells him, not this one. “I don’t want it to melt away.”

Kirsten Berg, Nadia Sussman and Mauricio Rodríguez Pons contributed reporting. Additional design and development by Lena V. Groeger.