Arise Virtual Solutions violates the rights of customer service agents around the country, a lawsuit filed last week in federal court asserts. The company, the suit claims, gets away with “flagrant legal violations” by keeping “its workers in the dark about their rights.”

The suit is attempting to turn one of Arise’s biggest legal advantages — that its workers agree to individual arbitration, which prevents them from taking coordinated legal action — against the company. Shannon Liss-Riordan, the plaintiffs’ lawyer bringing the suit, has asked the court to order Arise to provide her the names and contact information of the company’s customer service agents. (Its CEO said last year that Arise has about 70,000 agents.) That could allow Liss-Riordan, who has tangled with Arise for years in court and private arbitration, to notify those workers of their potential legal claims. If she signs up enough agents as clients, she could unleash a wave of arbitration filings against Arise in what could become a war of attrition.

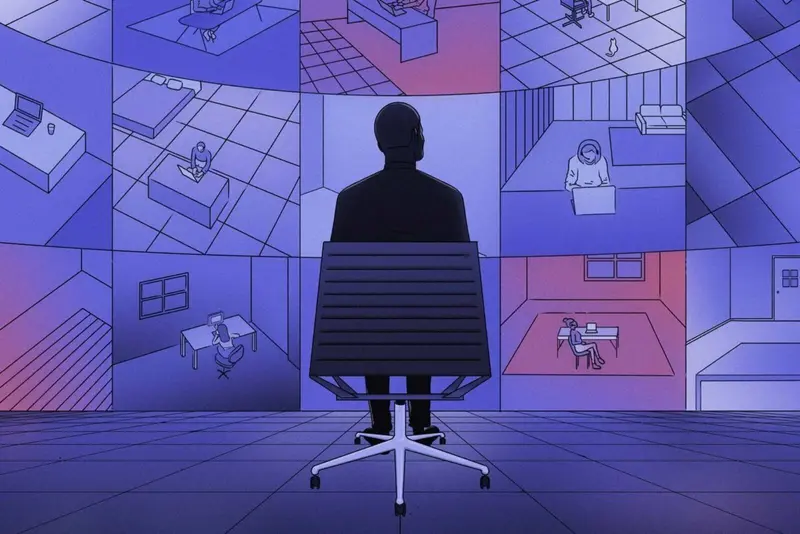

ProPublica investigated Arise last year, and that reporting is cited throughout the lawsuit. (ProPublica also partnered with NPR’s Planet Money on a podcast episode that featured Liss-Riordan’s attempts to hold Arise accountable.) Drawing on arbitration hearing transcripts, internal financial slides, corporate contracts and other records, our reporting showed how Arise has helped shape an underground industry that allows major corporations to shed labor costs by outsourcing customer service to a vast network of agents who work from home. The outsourcing is meant to be discreet: Agents are even forbidden from disclosing publicly the brand-name companies whose customers’ calls they take.

Arise, a private company headquartered in Florida, sells the services of its customer service representatives to such well-known brands as Disney and Airbnb. Arise says its agents are independent contractors; agents sign forms saying as much. But Liss-Riordan claims they are in effect Arise employees who are being deprived by the company of overtime, minimum wage and other protections provided by federal law.

Her suit alleges that Arise violates the U.S. Fair Labor Standards Act by misclassifying agents as freelancers while exercising such extensive control over them through training dictates, mandatory equipment expenditures and other work requirements that they are actually employees and should be paid accordingly. Liss-Riordan has made this argument before and prevailed — before at least two arbitrators and before an administrative law judge with the National Labor Relations Board. (ProPublica reported this year that a Department of Labor investigator reached the same conclusion and estimated Arise owed workers $14.2 million; Arise’s lawyers, however, “politely disagreed,” and the Labor Department let the matter drop.)

Arise has not yet filed a response to the new suit, and it declined to comment for this story. In previous suits the company has said its practices are lawful and transparent. In a statement provided to ProPublica last year, Arise said its business model is based on “freedom of choice” and that “the opportunities it provides have overwhelmingly shown positive outcomes” for agents who sign up.

Liss-Riordan has been stymied in her effort to mount a class action on behalf of Arise’s agents. That’s because Arise, like many other companies, requires workers to pursue claims through individual arbitration. At least three times before, Arise has gotten class actions bounced out of court based on those mandatory arbitration agreements. Arise could well request the same result in this latest lawsuit. Arise, the recent lawsuit contends, has succeeded “in using its mandatory arbitration agreements to shield itself from the law,” and it is “still engaging in the same illegal conduct,” even after arbitrators have ruled against the company and its business model.

This time, Liss-Riordan is preparing a possible workaround, or at least a new way to gain leverage against Arise: her motion asking the U.S. District Court to order Arise to turn over a list of all of its agents’ names in the past three years, along with their contact information. Armed with that list, Liss-Riordan could reach out to those agents to let them know they may have a legal claim against the company — in court or, if need be, in arbitration.

That could open the possibility of forcing Arise to defend hundreds or thousands of individual arbitration claims, a legal strategy that has caught hold in recent years with plaintiffs’ lawyers against corporations such as DoorDash, Comcast and AT&T. Last year, a federal judge in California ordered DoorDash to pay an arbitration filing fee for each claim filed by delivery drivers. Each fee was $1,900. There were 5,010 drivers. For DoorDash that meant a tab, just for filing fees, of $9.5 million. “The only thing they’ve got left is the right to arbitrate,” the judge said of the drivers, according to a transcript of the hearing. Referring to the millions in filing fees, the judge told DoorDash’s legal counsel, “That’s what you bargained to do, and you’re going to do it.”

Without a court-ordered list, finding and contacting Arise’s network of customer service agents would present significant challenges. The agents work at home. They’re isolated from one another. There’s no water cooler to gather around, no break-room message board to help spread the word. Allowing Arise to keep its list of agents confidential “would allow Arise to not only avoid being held accountable in court, but in arbitration too,” Liss-Riordan wrote in her motion.

For lawyers representing a class of workers, taking claims, one by one, to arbitration is not efficient. The process burns up lots of time in exchange for payouts that can be small. Corporations have long banked on that inefficiency to dissuade litigation. But if lawyers representing workers go ahead and take on the task, that inefficiency can turn against the company, which could be forced to pay a host of arbitration and attorney fees in a long succession of cases.

In 2014, Liss-Riordan represented a Houston woman in an arbitration case against Arise. The arbitration hearing lasted two days. Arise was represented by three lawyers. An Arise executive who lived in Florida traveled to Texas to testify. Liss-Riordan’s client won, with the arbitrator ruling that the agent had functioned as an employee, no matter Arise’s insistence that she was an independent contractor. The arbitrator ordered Arise to pay the woman $5,841.82 for unpaid minimum wage, training time and equipment expenses. Then the arbitrator doubled the damages, finding that Arise had no sound legal basis for believing it had been in the right. So Arise paid $11,683.64 in damages, on top of whatever it spent in fees, attorney costs and assorted other expenses.

One case with costs like that might be negligible for a company like Arise. But now imagine thousands of such cases — a grinding war that could sap the company’s attention and finances. To Liss-Riordan, that’s what getting the list of Arise’s reps could mean. “We’re prepared to file hundreds or thousands of arbitration claims if we need to,” she told ProPublica.

Liss-Riordan, who’s based in Boston, has a long history of going after major corporations. She has taken on Uber, FedEx, Amazon and others, accusing them of cheating employees by misclassifying them as independent contractors. She recently made a bid for the U.S. Senate but dropped out last year before the Democratic primary in Massachusetts.

In the lawsuit filed last week, Liss-Riordan attached declarations from four women who previously worked as agents in the Arise network. Their accounts detailed the kinds of costs that agents typically absorb as independent contractors. In addition to paying $10 to $40 a month for landline phones, the four women described buying all kinds of office equipment, including computers, monitors, headsets, Ethernet cords, keyboards, webcams, printers and upgraded Wi-Fi. One former agent estimated her equipment costs to be $3,800.

Liss-Riordan filed the lawsuit in Missouri, one of seven states that fall under the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit. That was by design. Two federal appeals courts, in the 5th and 7th circuits, have refused the kind of request she’s making, for a list of potential claimants in a collective lawsuit where the case could well be bounced to arbitration.

But within the 8th Circuit, a number of U.S. District Courts have gone the opposite way and ordered companies to produce such lists. “So we tried to pick a circuit where we might get a better outcome,” Liss-Riordan said. A recent example occurred in Iowa, where, in April, a federal judge ordered a strip club to provide a list of exotic dancers it had classified as independent contractors rather than employees.

Justin Elliott contributed reporting.