Nearly four years after a woman ended an unwanted pregnancy with abortion pills obtained at a Phoenix clinic, she finds herself mired in an ongoing lawsuit over that decision.

A judge allowed the woman’s ex-husband to establish an estate for the embryo, which had been aborted in its seventh week of development. The ex-husband filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the clinic and its doctors in 2020, alleging that physicians failed to obtain proper informed consent from the woman as required by Arizona law.

Across the U.S., people have sued for negligence in the death of a fetus or embryo in cases where a pregnant person has been killed in a car crash or a pregnancy was lost because of alleged wrongdoing by a physician. But a court action claiming the wrongful death of an aborted embryo or fetus is a more novel strategy, legal experts said.

The experts said this rare tactic could become more common, as anti-abortion groups have signaled their desire to further limit reproductive rights following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade. The Arizona lawsuit and others that may follow could also be an attempt to discourage and intimidate providers and harass plaintiffs’ former romantic partners, experts said.

Lucinda Finley, a law professor at the University at Buffalo who specializes in tort law and reproductive rights, said the Arizona case is a “harbinger of things to come” and called it “troubling for the future.”

Finley said she expects state lawmakers and anti-abortion groups to use “unprecedented strategies” to try to prevent people from traveling to obtain abortions or block them from obtaining information on where to seek one.

Perhaps the most extreme example is in Texas, where the Texas Heartbeat Act, signed into law in May 2021 and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in December, allows private citizens to sue a person who performs or aids in an abortion.

“It’s much bigger than these wrongful death suits,” Finley said.

Civia Tamarkin, president of the National Council of Jewish Women Arizona, which advocates for reproductive rights, said the Arizona lawsuit is part of a larger agenda that anti-abortion advocates are working toward.

“It’s a lawsuit that appears to be a trial balloon to see how far the attorney and the plaintiff can push the limits of the law, the limits of reason, the limits of science and medicine,” Tamarkin said.

In July 2018, the ex-husband, Mario Villegas, accompanied his then-wife to three medical appointments — a consultation, the abortion and a follow-up. The woman, who ProPublica is not identifying for privacy reasons, said in a deposition in the wrongful death suit that at the time of the procedure the two were already talking about obtaining a divorce, which was finalized later that year.

“We were not happy together at all,” she said.

Villegas, a former Marine from Globe, Arizona, a mining town east of Phoenix, had been married twice before and has other children. He has since moved out of state.

In a form his then-wife filled out at the clinic, she said she was seeking an abortion because she was not ready to be a parent and her relationship with Villegas was unstable, according to court records. She also checked a box affirming that “I am comfortable with my decision to terminate this pregnancy.” The woman declined to speak on the record with ProPublica out of fear for her safety.

The following year, in 2019, Villegas learned about an Alabama man who hadn’t wanted his ex-girlfriend to have an abortion and sued the Alabama Women’s Center for Reproductive Alternatives in Huntsville on behalf of an embryo that was aborted at six weeks.

To sue on behalf of the embryo, the would-be father, Ryan Magers, went to probate court where he asked a judge to appoint him as the personal representative of the estate. In probate court, a judge may appoint someone to represent the estate of a person who has died without a will. That representative then has the authority to distribute the estate’s assets to beneficiaries.

When Magers filed to open an estate for the embryo, his attorney cited various Alabama court rulings involving pregnant people and a 2018 amendment to the Alabama Constitution recognizing the “sanctity of unborn life and the rights of unborn children.”

A probate judge appointed Magers representative of the estate, giving him legal standing to sue for damages in the wrongful death claim. The case, believed to be the first instance in which an aborted embryo was given legal rights, made national headlines.

It’s unclear how many states allow an estate to be opened on behalf of an embryo or fetus. Some states, like Arizona, don’t explicitly define what counts as a deceased person in their probate code, leaving it to a judge to decide. In a handful of states, laws define embryos and fetuses as a person at conception, which could allow for an estate, but it’s rare.

An Alabama circuit court judge eventually dismissed Magers’ wrongful death lawsuit, stating that the claims were “precluded by State and Federal laws.”

Villegas contacted Magers’ attorney, Brent Helms, about pursuing a similar action in Arizona and was referred to J. Stanley Martineau, an Arizona attorney who had flown to Alabama to talk to Helms about Magers’ case.

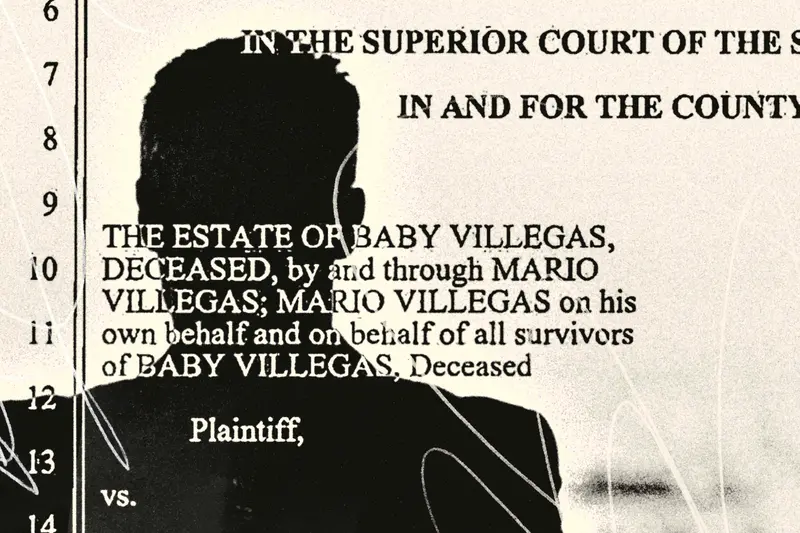

In August 2020, Villegas filed a petition to be appointed personal representative of the estate of “Baby Villegas.” His ex-wife opposed the action and contacted a legal advocacy organization focused on reproductive justice, which helped her obtain a lawyer.

In court filings, Villegas said he prefers to think of “Baby Villegas” as a girl, although the sex of the embryo was never determined, and his lawyer argued that there isn’t an Arizona case that explicitly defines a deceased person, “so the issue appears to be an open one in Arizona.”

In a 2021 motion arguing for dismissal, the ex-wife’s attorney, Louis Silverman, argued that Arizona’s probate code doesn’t authorize the appointment of a personal representative for an embryo, and that granting Villegas’ request would violate a woman’s constitutional right to decide whether to carry a pregnancy to term.

“U.S. Supreme Court precedent has long protected the constitutional right of a woman to obtain an abortion, including that the decision whether to do so belongs to the woman alone — even where her partner, spouse, or ex-spouse disagrees with that decision,” Silverman said last year.

Gila County Superior Court Judge Bryan B. Chambers said in an order denying the motion that his decision allows Villegas to make the argument that the embryo is a person in a wrongful death lawsuit, but that he has not reached that conclusion at this stage. Villegas was later appointed the personal representative of the estate.

As states determine what is legal in the wake of Dobbs and legislators propose new abortion laws, anti-abortion groups such as the National Right to Life Committee see civil suits as a way to enforce abortion bans and have released model legislation they hope sympathetic legislators will duplicate in statehouses nationwide.

“In addition to criminal penalties and medical license revocation, civil remedies will be critical to ensure that unborn lives are protected from illegal abortions,” the group wrote in a June 15 letter to its state affiliates that included the model legislation.

James Bopp Jr.,general counsel for the committee, said in an interview with ProPublica that such actions will be necessary because some “radical Democrat” prosecutors have signaled they won’t enforce criminal abortion bans. Last month, 90 prosecutors from across the country indicated that they would not prosecute those who seek abortions.

“The civil remedies follow what the criminal law makes unlawful,” he said. “And that’s what we’re doing.”

The National Right to Life Committee’s model legislation, which advocates prohibiting abortion except to prevent the death of the pregnant person, recommends that states permit civil actions against people or entities that violate abortion laws “to prevent future violations.” It also suggests that people who have had or have sought to have an illegal abortion, as well as the expectant father and the parents of a pregnant minor, be allowed to pursue wrongful death actions.

Under the legislation, an action for wrongful death of an “unborn child” would be treated like that of a child who died after being born.

In one regard, Arizona has already implemented a piece of this model legislation as the state’s lawmakers have chipped away at access to abortion and enacted a myriad of regulations on doctors who provide the procedure.

The state’s “informed consent” statute for abortion, first signed into law by then-Gov. Jan Brewer in 2009, mandated an in-person counseling session and a 24-hour waiting period before an abortion. It allows a pregnant person, their husband or a maternal grandparent of a minor to sue if a physician does not properly obtain the pregnant person’s informed consent, and to receive damages for psychological, emotional and physical injuries, statutory damages and attorney fees.

The informed consent laws, which have changed over time, mandate that the patient be told about the “probable anatomical and physiological characteristics” of the embryo or fetus and the “immediate and long-term medical risks” associated with abortion, as well as alternatives to the procedure. Some abortion-rights groups and medical professionals have criticized informed consent processes, arguing the materials can be misleading and personify the embryo or fetus. A 2018 review of numerous studies concluded that having an abortion does not increase a person’s risk of infertility in their next pregnancy, nor is it linked to a higher risk of breast cancer or preterm birth, among other issues.

The wrongful death suit comes at a time of extraordinary confusion over abortion law in Arizona.

Until Roe v. Wade was handed down in 1973, establishing a constitutional right to abortion, a law dating to before statehood had banned the procedure. In March, Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican who has called Arizona “the most pro-life state in the country,” signed into law a bill outlawing abortions after 15 weeks, and said that law would supersede the pre-statehood ban if Roe were overturned. But now that Roe has been overturned, Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich, another Republican, said he intends to enforce the pre-statehood ban, which outlawed abortion except to preserve the life of the person seeking the procedure. On Thursday, he filed a motion to lift an injunction on the law, which would make it enforceable.

Adding to the muddle, a U.S. district court judge on Monday blocked part of a 2021 Arizona law that would classify fertilized eggs, embryos and fetuses as people starting at conception, ruling that the attorney general cannot use the so-called personhood law against abortion providers. Following the Supreme Court decision in Dobbs, eight of the state’s nine abortion providers — all located in three Arizona counties — halted abortion services, but following the emergency injunction some are again offering them.

In the wrongful death claim, Martineau argued that the woman’s consent was invalidated because the doctors didn’t follow the informed consent statute. Although the woman signed four consent documents, the suit claims that “evidence shows that in her rush to maximize profits,” the clinic’s owner, Dr. Gabrielle Goodrick, “cut corners.” Martineau alleged that Goodrick and another doctor didn’t inform the woman of the loss of “maternal-fetal” attachment, about the alternatives to abortion or that if not for the abortion, the embryo would likely have been “delivered to term,” among other violations.

Tom Slutes, Goodrick’s lawyer, called the lawsuit “ridiculous.”

“They didn’t cut any corners,” he said, adding that the woman “clearly knew what was going to happen and definitely, strongly” wanted the abortion. Regardless of the information the woman received, she wouldn’t have changed her mind, Slutes said. Slutes referenced the deposition, where the woman said she “felt completely informed.”

Martineau said in an interview that Villegas isn’t motivated by collecting money from the lawsuit.

“He has no desire to harass” his ex-wife, Martineau said. “All he wants to do is make sure it doesn’t happen to another father.”

In a deposition, Villegas’ ex-wife said that he was emotionally abusive during their marriage, which lasted nearly five years. At first, she said, Villegas seemed like the “greatest guy I’ve ever met in my life,” taking her to California for a week as a birthday gift. But as the marriage progressed, she said, there were times he wouldn’t allow her to get a job or leave the house unless she was with him.

The woman alleged that Villegas made fake social media profiles, hacked into her social media accounts and threatened to “blackmail” her if she left him during his failed campaign to be a justice of the peace in Gila County, outside of Phoenix.

Villegas denied the allegations about his relationship but declined to comment further for this story, Martineau said.

Carliss Chatman, an associate law professor at Washington and Lee University in Virginia, said certain civil remedies can also be a mechanism for men to continue to abuse their former partners through the court system.

“What happens if the father who is suing on behalf of the fetus is your rapist or your abuser? It’s another way to torture a woman,” Chatman said.

Chatman added that these legal actions can be a deterrent for physicians in states where abortion is banned after a certain gestational period, because the threat of civil suits makes it harder for doctors to get insurance.

The lawsuit has added to the stresses on Goodrick, who has been performing abortions in Arizona since the mid-1990s, and her practice. She said that since the lawsuit was filed, the annual cost of her medical malpractice insurance has risen from $32,000 to $67,000.

Before providers in Arizona halted abortions following the Supreme Court decision, people would begin lining up outside Goodrick’s clinic at 6 a.m., sometimes with lawn chairs in hand, like “a concert line,” Goodrick said.

“Every year there’s something and we never know what it’s going to be,” Goodrick said recently at her Phoenix clinic. “I’m kind of desensitized to it all.”