As the U.S. rushes to vaccinate its population against the coronavirus, most counties with the sickest residents are lagging behind and making only incremental progress reaching their most vulnerable populations.

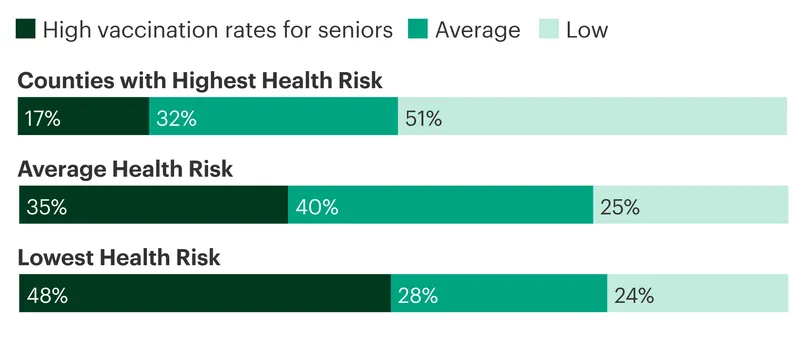

A ProPublica analysis of county data maintained by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that early attempts to prioritize people with chronic illnesses like heart disease, diabetes and obesity have faltered. At the same time, healthier — and often wealthier — counties moved faster in vaccinating residents, especially those 65 and older. (Seniors are a more reliable measure of vaccination progress than younger adults, who are less likely to have been eligible long enough to receive their second shots.) Counties with high levels of chronic illnesses or “comorbidities” had, on average, immunized 57% of their seniors by April 25, compared to 65% of seniors in counties with the lowest comorbidity risk.

A similar gap has also opened for all other adults. The one-third of counties with the highest chronic illness risk have on average finished shots for 15% of their 64-and-under residents, four percentage points below the average for the healthiest one-third of counties.

In counties with high rates of chronic disease, residents are more likely to die prematurely from heart or pulmonary diseases, diabetes or illnesses related to smoking or obesity. Those conditions also increase a person’s risk of developing severe COVID-19.

People with chronic illnesses are especially important to vaccinate because their coronavirus infections are more likely to end in hospitalization and death, said Janet Baseman, an epidemiology professor at the University of Washington. If counties with high comorbidities remain behind, she said, “then we are not accomplishing our objective, as communities or as a nation, of saving lives.”

Counties With the Highest Health Risks Have the Lowest Vaccination Rates Among Seniors

In the four months since public vaccinations began, clear disparities have emerged in how quickly the richest and poorest counties have delivered shots to their residents. Multiple health experts and officials say the numbers underscore a key strategic misstep under the Trump administration, which asked state and local governments to prioritize people with illnesses that would increase their chances of hospitalization or death, but provided no additional funding to support the efforts.

Many states chose a simpler approach, opening vaccine appointments to everyone 65 and older with minimal on-the-ground outreach to people with chronic illnesses. “It made some states go a little bit faster,” said Dr. Grace Lee, a member of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and an infectious diseases physician at Stanford Children’s Health. “But I think it really increased the inequities early on.”

When vaccinations started in December and January for the general population, the federal Department of Health and Human Services distributed free doses and supplies, but almost no money or staffing to administer the shots. State and local health officials had to decide who would first be eligible for the small amounts of vaccine then available and how to get doses into arms. They also had to watch for interlopers — many of them young, white and from other locations — who booked appointments they didn’t qualify for.

In counties with more chronic illness, identifying the neighborhoods and housing complexes where residents or critical workers most need the shots — and then actually getting them to accept vaccinations — can be complicated, time-consuming work. Health officials in several counties with high rates of chronic illness said they are making slow progress by focusing resources on small events and mobile teams instead of on sprawling mass vaccination sites.

ProPublica focused on comorbidities because they are directly related to increased risk of developing severe COVID-19. People with lower incomes are more likely to have comorbidities; urban counties with high average incomes tend to have fully immunized a larger share of their older residents than other counties. In addition to income, the analysis looked at the urban and rural divide, age demographics and differences between states’ overall vaccination rates.

While communities of color have disproportionately high rates of chronic illness nationally, the analysis found no relationship between counties’ racial demographics and coronavirus vaccination rates.

The rollout has largely relied less on government outreach than on individual initiative. People with flexible schedules, transportation and regular access to the health care system have been better able to get appointments on their own or with help from family and friends. Those with less support have fallen behind.

Separately, surveys by the CDC last year indicated that adults with underlying medical conditions were less interested in getting the vaccine than healthier adults. People surveyed who said they were unlikely to get vaccinated most often cited concerns about side effects and safety.

To date, more than 98 million people in the U.S. — including 37 million seniors — are fully vaccinated against the coronavirus, while another 150 million adults have yet to receive a shot. During an address to a joint session of Congress on Wednesday, President Joe Biden heralded the vaccination effort as “one of the greatest logistical achievements” in the country’s history.

The push continues even as demand for shots appears to be declining, said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

Providers injected more than 21.7 million doses during the second week of April, according to CDC data, as the supply of vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson increased significantly. That number declined to 19.2 million shots the next week, and preliminary figures indicate immunizations dropped even more sharply last week. (Federal authorities temporarily paused use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine for 10 days to study a small number of blood clot cases potentially related to the shot. It has since been cleared for use.)

There probably aren’t yet enough fully vaccinated people in the U.S. to protect against another surge, Osterholm said, especially with the more transmissible coronavirus variants now prevalent. In Michigan, new cases again soared in April, setting records for daily COVID-19 hospitalizations.

“We’re not out of the woods yet in this country,” Osterholm said. “What happened in Michigan could still happen in a number of other states out there. Even with the level of vaccination they’ve had and the previous infections, look what still happened.”

Reaching the most vulnerable has been a top concern for many of the poorest cities and counties since vaccinations began.

In Baltimore, COVID-19 caused far more severe illness and death in the majority-Black city’s communities of color, where people with chronic illnesses are more common, according to Dr. Letitia Dzirasa, the city health commissioner. During the first month of the vaccine rollout, the Baltimore health department realized it needed different tactics for immunizing its seniors.

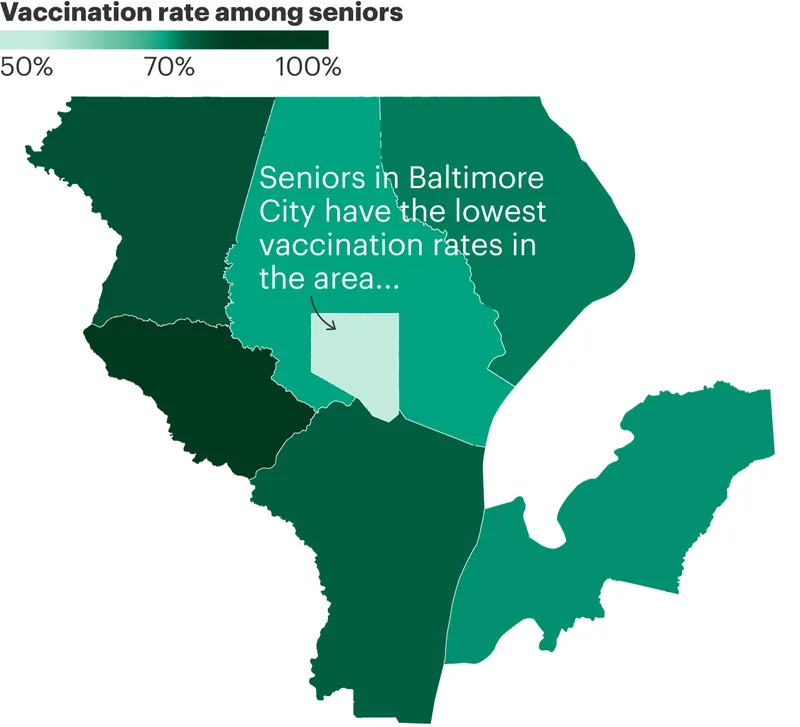

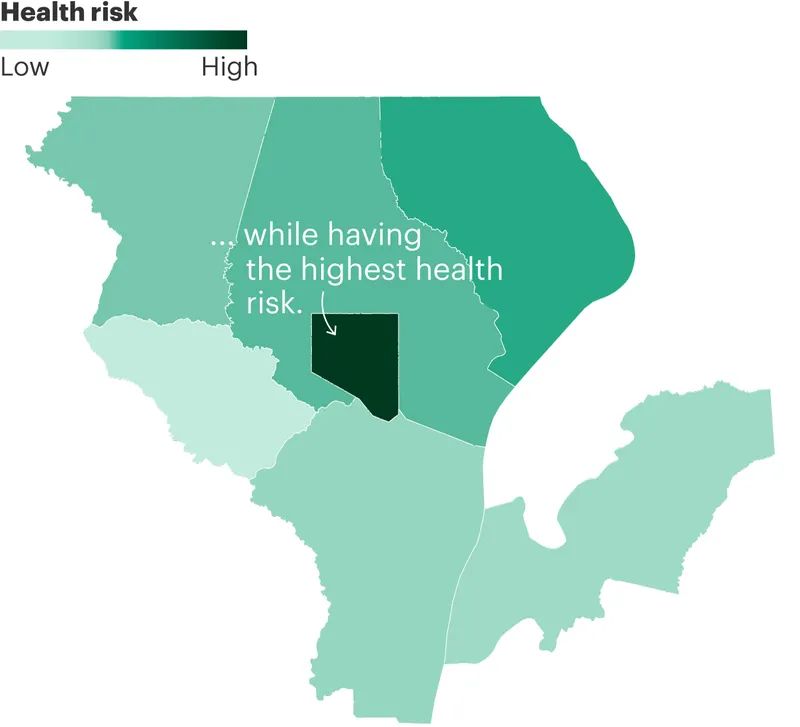

The city of Baltimore has the highest rates of diabetes, smoking and obesity of the seven counties in its metro area, and its premature death rate is nearly double that of its neighboring counties, data from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences shows. It ranks among the nation’s most at-risk jurisdictions from chronic illness. Other parts of the region, like the more affluent nearby Howard County, are among the healthiest.

CDC data shows just 55% of Baltimore City’s seniors were fully vaccinated as of April 25, 15 percentage points lower than the rate for residents 65 and older in larger Baltimore County, which surrounds the city.

Counties in the Baltimore Metro Area With the Lowest Vaccination Rates Among Seniors Have Some of the Highest Health Risks

Within Baltimore, Dzirasa said, the pandemic hit hardest in Black neighborhoods on the city’s east and west sides, where residents have long struggled against discrimination, poverty and chronic illnesses. “Unfortunately, we’ve seen the same thing again with vaccination rates,” she said.

The city health department knew that many of its most vulnerable seniors would have no transportation to vaccination sites, and that their senior living centers were less likely than facilities in wealthier communities to have relationships with pharmacies to secure doses.

In January, Dzirasa said, her staff partnered with hospitals and pharmacies to create mobile vaccine teams that could deliver shots directly to those most at risk of severe COVID-19.

The first step was to win residents’ trust with visits to centers from community health workers, who explained the vaccines, provided reassurance and scheduled appointments. The teams identified 117 senior living centers and have immunized residents one by one at almost every facility over the past three months.

“It’s definitely a slower approach,” Dzirasa said. “At these events, we’re doing anywhere from 75 to 150 people, tops.”

Baltimore has multiple mass vaccination sites that can each provide from hundreds to thousands of shots a day. A couple of months ago, all site appointments were booked, and ineligible people had to be weeded out, Dzirasa said. Now, those spots are increasingly unfilled, and Dzirasa expects gradual progress going forward.

The disparity in vaccination rates between counties with high rates of chronic illness and the rest of the country is partly the result of the Trump administration’s decision not to invest federal dollars in vaccine sites at the beginning, argues Lee.

“They launched this massive campaign and were like, ‘Good luck, you’re on your own,’” Lee said. “And not only do you have to deliver a very complicated series of vaccines, but on top of that we expect you to address inequities, all without any additional support.”

The Biden administration set up several mass vaccination sites in high-risk communities in February and has now sent federal workers, equipment or funds to operate more than 400 vaccination sites nationwide. But many counties with high rates of comorbidity are still working to make up for a slow start.

The winter COVID-19 surge was peaking when vaccine doses started to arrive in Wyandotte County, part of Kansas City’s urban core. Small deliveries containing about 2,000 doses arrived each week from the federal government, said Dr. Erin Corriveau, the county’s deputy medical officer.

At first, only health care workers and nursing home residents qualified to be vaccinated. Then, on Jan. 21, Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly opened eligibility to everyone 65 and older, including more than 20,000 seniors in Wyandotte County.

“We’re going, ‘Oh my God, that’s a huge number of people,’” Corriveau recalled. The county decided to set its own eligibility rules, since it was still receiving just 2,000 doses a week.

Most new COVID-19 cases at the time were young adults. To help drive down case numbers, Corriveau said, the county temporarily narrowed eligibility to just residents 85 and older while adding critical workers whose jobs exposed them to greater infection risk.

Wyandotte County opened the shots to all seniors a few weeks later as case numbers dropped. But the demand for shots was modest, Corriveau said, especially compared to the clamor in other parts of the country, where older Americans struggled to find providers with available doses.

The county now runs three mass vaccination sites located on bus routes, with assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. It keeps pharmacies stocked with vaccines, and dispatches “drop teams” to administer shots at small neighborhood operations. Doses are plentiful, but willing recipients are scarce. Corriveau said many of the county’s seniors are wary about the vaccines’ safety and have been unwilling to get the shots at large, impersonal sites.

“We’ve tried to make this vaccine as available as humanly possible,” she said. “We’re incentivizing vaccines with giveaways and food boxes and we’re doing Saturday hours and expanding our evening hours.”

Despite those efforts, only 56% of seniors in Wyandotte County were fully vaccinated as of April 25. A few miles south, in Johnson County, more than 83% were immunized.

The neighboring jurisdictions have little in common with each other. Wyandotte, meanwhile, stands out as being more diverse, with residents who suffer from far more chronic illness. Wyandotte’s rate of premature death is double Johnson’s rate, according to NIH data.

Tami Gurley, associate professor of population health at the University of Kansas Medical Center, said Johnson County has longstanding advantages that likely helped its residents get vaccinated so quickly.

“You have people with time, who can get on computers and sign up for multiple lists,” Gurley said. “They all have their own transportation, nobody’s relying on public transportation, it’s all private cars out here.”

The university medical center where Gurley works is located in Wyandotte and cares for its residents, she said. But many of its health workers live in other parts of Kansas City, including Johnson County. “That is where the doctors live, and the professors, and the people who tend to be more pro-vaccine to start with,” she said.

Wyandotte’s health officials are trying to reassure residents that the shots are safe and that communities of color can trust the county health department. “Frankly, there have been major, major issues of trust,” Corriveau said of residents’ view of local agencies, “which are warranted.”

She and her colleagues are increasingly asking trusted community leaders to stand in for epidemiologists. Throughout the pandemic, Rev. Tony Carter, Jr., senior pastor of Salem Missionary Baptist Church, has encouraged his congregation to test for the virus, follow health protocols and, in recent months, get vaccinated.

Carter’s church volunteered to host a Saturday neighborhood vaccine event on April 17, and nearly 50 people signed up for appointments to get the Johnson & Johnson shot. But several days before the event, federal authorities paused use of that vaccine as they investigated six cases of serious blood clots among the 6.8 million people who had received it. (The U.S. resumed use of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine without limitations on April 23.)

The county switched to another vaccine, but half of the recipients canceled their appointments. Carter reassured his congregants that the vaccine would offer a way of eventually reuniting with family. About two dozen people kept their appointments and received their first vaccine dose. “Most of those people stayed because of their connection to the church,” he said.