In the high-stakes world of high-speed, short-term securities trading, investors can reap massive payouts but often face higher tax rates due to the nature of their business. But one of America's richest men somehow earns billions from speedy trades while paying a tax rate lower than many middle-class Americans.

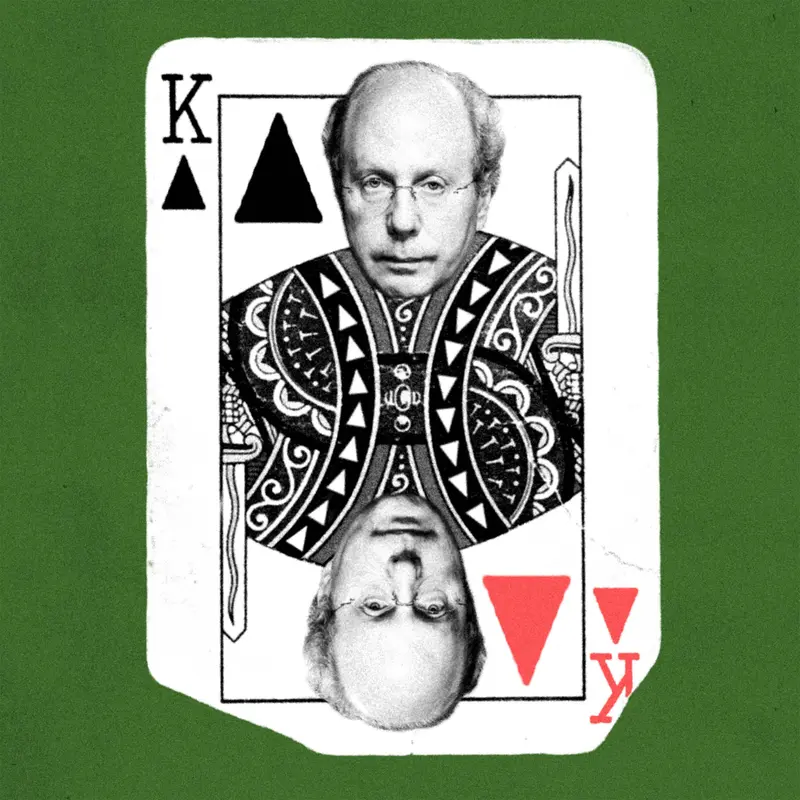

The Man

Among dozens of Wall Street billionaires whose tax returns ProPublica examined, one stood out: Jeff Yass of Susquehanna International Group.

The Mystery

Yass consistently pays lower tax rates than his peers, even as he has risen to be one of the top 10 highest earners in the country, receiving more than $1 billion per year in income. He paid an average federal income tax rate of just 19% in recent years, far below what many of his fellow Wall Street billionaires pay. That has saved Yass more than $1 billion in taxes over six years, ProPublica estimates.

What has made this pattern all the more remarkable is the nature of Susquehanna’s business: The firm was built on high-frequency trading, which tends to produce short-term gains; these are taxed at around 40%. And yet, year after year, Yass’ income has been taxed almost entirely at the 20% rate reserved for longer-term investments. (For more details, read our full story.)

So How Does He Do It?

ProPublica spoke to former Susquehanna employees and examined court records, securities filings and tax records to find out how Yass managed this. Taxes, according to Yass’ former colleagues, are an obsession for the billionaire and his fellow executives. As one former employee put it, “They hate fucking taxes.”

Susquehanna has crafted aggressive multibillion-dollar trading strategies that appear designed to slash its tax bill.

One main engine of Yass’ tax avoidance, ProPublica found, is a huge investment fund called Susquehanna Fundamental Investments. Every year, like clockwork, the fund effectively wipes out hundreds of millions of dollars worth of Yass’ income that would otherwise get hit at the highest tax rates, while generating hundreds of millions in income that is taxed at the lower rate.

Regulatory filings give a glimpse of the fund’s trading. The fund has to disclose a snapshot of certain holdings to the Securities and Exchange Commission a few times each year, though many types of trades are exempt from disclosure.

Over several years, the fund held billions of dollars of individual stocks in such companies as Google, Wells Fargo and Coca-Cola. These stocks are among the largest companies in the S&P 500 index. Meanwhile, the fund also held a large bet against the S&P 500. In essence, it held a bet against many of those exact same stocks.

Experts say that the counterintuitive strategy of simultaneously betting for and against the market can yield tax benefits. Essentially, it can offer a relatively low-risk way to generate short-term losses and long-term gains.

The short-term losses can be used to wipe away other short-term gains that would get taxed at almost 40%. Yass’ high-speed trading business generates hundreds of millions of these gains each year. The long-term gains replace the lost income, but get taxed at a much lower rate of around 20%. For every $100 run through this process, a trader would net from $17 to $20 in tax savings, depending on prevailing rates.

The IRS Says You Can’t Do Straddles, But…

Because of the potential for abuse, there are intricate rules in the tax code barring certain kinds of bets for and against the same securities. These are known as “straddles” because the trader is standing on both sides of the same bet. (For a step-by-step on how straddles work, read our full story.)

It’s not clear whether the IRS has ever challenged Susquehanna Fundamental’s trades. But the agency has gone after Yass and his partners in other cases, resulting in bills for back taxes totaling more than $100 million.

In one recent case, the IRS found that Susquehanna violated restrictions on betting for and against the same stocks. Court records from the case show the firm bought more than $1 billion worth of Swiss stocks, while taking out equal bets against the same stocks at the same time and claiming tax savings in the process.

The firm is disputing that the trades were designed primarily to save money on taxes, and in 2020 sued the IRS in federal court to dispute its tax bill. It has maintained in court filings that it complies with all legal requirements. The case is still pending.

A spokesperson for Susquehanna and Yass declined to comment in response to detailed questions from ProPublica.