Kim Fuller needed to move. Her 83-year-old mom was struggling to get around the narrow, three-story row house they shared in Baltimore. Heart problems made climbing the stairs too arduous, cutting the older woman off from the kitchen where she’d loved to cook.

Fuller, 57, found an apartment complex 3 miles away that billed itself as “luxury living” for people 55 and older, and she applied for a unit in early 2021. She figured she’d be approved: Her salary as a mental health services coordinator for the state of Maryland met the income requirements. She’d never been evicted and had brought her credit score up to 632 — which is considered fair — after a health crisis had forced her to file for bankruptcy eight years earlier.

Still, a few months later, when she logged into her online account with the property manager, she learned her application had been denied. No reason was given. She raised her credit score to 663 and applied to another complex owned by the same company, Habitat America, in August. Six days later her status again turned to “Declined.”

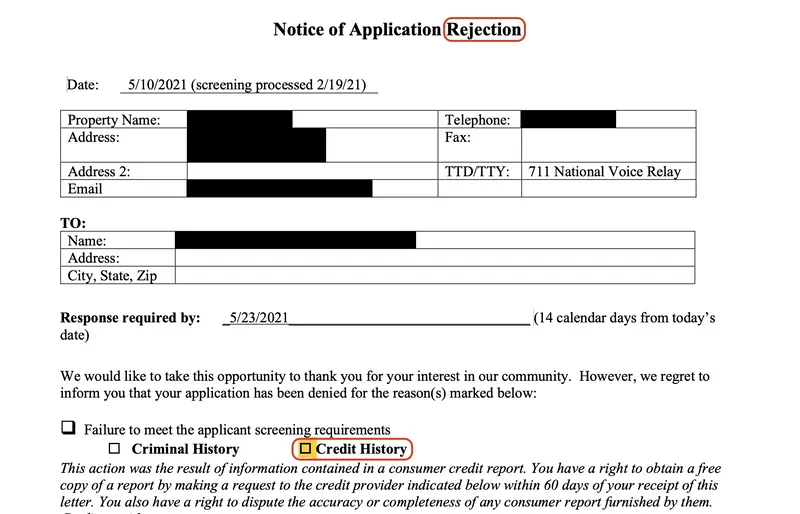

Fuller learned her rental application had been screened by RentGrow, one of more than a dozen companies that mine consumer databases to perform background checks on tenants. A form emailed to her said RentGrow determined she didn’t meet applicant screening requirements, highlighting in yellow the box labeled “credit history” as the reason.

The letter provided no further explanation. A RentGrow representative, through an executive at its parent company, declined to comment. Habitat America declined to respond to questions about Fuller’s application from ProPublica, citing privacy concerns.

“You don’t know why you got denied or if you were ever considered,” Fuller said. “It’s really murky out there.”

Fuller’s experience has become more common as landlords have increased their reliance on tenant screening to help them select renters. The industry has expanded dramatically as the number of renters has grown and new technology has made it easier to access vast troves of data, such as court records.

Tenant screening companies compile information beyond what’s in renters’ credit reports, including criminal and eviction filings. They say this data helps give landlords a better idea of who will pay on time and who will be a good tenant. The firms typically assign applicants scores or provide landlords a yes-or-no recommendation.

A ProPublica review found that such ratings have come to serve as shadow credit scores for renters. But compared to credit reporting, tenant screening is less regulated and offers fewer consumer protections — which can have dire consequences for applicants trying to secure housing.

Frequent errors on tenant screening reports, often related to false eviction reports or criminal records, led government watchdogs to admonish the industry last year to improve its accuracy. (The Markup reported a series of stories on the industry and regulators’ reactions to it.)

Yet errors are just one of the problems with tenant screening, ProPublica found. Tenants often can’t get enough information to understand why they were marked as a risk to landlords.

More than 40 renters responded to a ProPublica survey last year about tenant screening. Some were denied housing. Others were asked to pay double or triple deposits because of low tenant scores.

“It’s kind of chaos,” said Ariel Nelson, a staff attorney at the National Consumer Law Center. “It’s really hard to figure out if you were rejected, why was it rejected. If it’s something you can fix or if it’s an error.”

The algorithms some screening companies use aren’t scrutinized by regulators and, tenant advocates say, may not accurately predict a tenant’s likelihood of paying rent. While screening companies say their algorithms remove the subjectivity of human judgment, advocates say the companies use data that can introduce racial or other illegal biases.

Fuller, who is Black, worried she might have been a victim of racial discrimination.

Her case baffled Carol Ott at the Fair Housing Action Center of Maryland. “You’re fighting against the company that uses secret algorithms,” said Ott, the center’s tenant advocacy director. “Where do you even go with that?”

Regional Property Manager Karin Scott said in an email that Habitat America’s policy is to treat all residents and visitors fairly, and “any concerns that a denial was based upon racial discrimination are unfounded.”

To be sure, the credit reporting industry also draws criticism from consumer advocates for failing to keep errors off credit reports and for using algorithms that critics say perpetuate racial biases.

ProPublica found that tenant screening receives even less oversight than credit reporting, which has been litigated intensely and is watched by the courts and federal agencies in an effort to minimize unfair treatment.

Federal agencies have “supervisory authority” to review the internal records of financial institutions such as banks to ensure that their scoring methods are predictive, statistically sound and nondiscriminatory, experts said.

A parallel process does not exist for tenant screening.

“Nobody’s supervising. Nobody’s checking the data,” said Chi Chi Wu, an attorney at the National Consumer Law Center. “Nobody’s checking these algorithms.”

A spokesperson for the Consumer Data Industry Association, which represents consumer reporting agencies, including screening companies, said in an emailed statement that the competitive tenant screening market pushes companies to continuously improve their tools for helping landlords comply with fair housing and other laws.

“Consumers expect and demand safe places to live, and our tenant screening members help protect residential communities, especially their most vulnerable populations,” the statement said.

The National Apartment Association, a trade group representing apartment owners and managers, said it supports new technology for rental operations and encourages members to research vendors to make sure they comply with regulations, according to a statement from Senior Vice President Greg Brown.

“Rental housing providers are committed to equal housing opportunity and utilize resident screening tools through this lens to balance risks that could impact the entire community,” Brown said.

“High-Risk Renters”

The rapid rise of tenant screening is one of the seismic changes to hit the rental market since the Great Recession. As ProPublica has reported, private equity firms have poured into the multifamily apartment market, often driving up rents in search of greater profits than those typically sought by mom-and-pop landlords. Algorithms now often replace human judgment in deciding who qualifies for housing and how much rent costs.

Bob Withers, a retired executive for corporate landlords and regional property managers, said when he left the industry temporarily in 2006, credit checks were still landlords’ main tool for assessing applicants.

“When I came back in 2010 or 2011, things had changed so much that everyone I knew was using tenant screening companies,” he said.

Nearly 2,000 companies offered background screening in 2019, most for either employment or tenant purposes, an industry survey found. It estimated that tenant screening brought in roughly $1 billion in annual revenue.

RealPage, a leading Texas-based property management tech firm, boasts that its algorithm uses artificial intelligence to “identify high-risk renters with greater accuracy.” The company says it uses a massive, proprietary database of 30 million lease outcomes, paired with consumer financial data, to evaluate rental applicants.

“This model is materially more effective than traditional screening solutions, with an average proven savings of $31 per apartment per year without negative impact to occupancy or revenue,” a company media release said.

RealPage did not respond to questions about the release.

Tenant score algorithms try to predict how risky it is to rent to a potential tenant based on characteristics they share with other tenants, according to Jean Noonan, an attorney and former Federal Trade Commission official whose law firm represents tenant screening companies.

“A scoring model may find that certain characteristics help predict risk,” said Noonan. “They don’t predict it perfectly for every individual. Overall, they do a satisfactory job of predicting risk.”

Yet Withers, the retired regional property manager, said it was typical that several times a month he would need to override denial recommendations from the screening service his firm used. Often, it was because people had medical debt, foreclosures or student loans but otherwise looked like good candidates.

“If everything else looked clean to me, I would do an override,” said Withers, who oversaw thousands of apartments in Maryland and Virginia. Busy property managers may not realize that the screening service’s algorithm was set up in a way that would reject people who might be viable candidates, he added.

Tenant advocates say the consumer data used by screening companies too often results in negative recommendations for reasons that are not proven indicators of how good a tenant someone would be. One tenant in Washington state who contacted ProPublica received a screening letter that listed “too many different phone numbers reported” as a risk factor that contributed to lowering her tenant score.

Some of the personal details that screening companies are plugging into algorithms to rate potential tenants may reflect racial biases, tenant advocates said.

“We don’t know whether they’re predictive,” Nelson said. “Based on what little information we have about what factors go into them, we are concerned about racial disparities.”

A negative screening can not only result in a denial, it can also prompt a landlord to demand a higher deposit, potentially deterring the renter from taking the apartment at all.

Chloe Crawford is an artist who found an apartment to live in while she worked on her masters degree at Rutgers University. But when she arrived at her new building near campus in September 2018, possessions in tow, her new landlord asked for an extra month’s rent as a deposit because of her low tenant screening score, she said. The total deposit added up to more than $1,000. It was more than she planned to spend on a month’s worth of groceries, and her car needed repairs.

Though Crawford expected to devote a high percentage of her income to rent because she was attending classes, she had money in the bank, had lined up an on-campus job and had been careful to pay her bills on time to keep her credit score high.

Her credit score of 788 out of 850 was considered very good, high enough that she could qualify for a mortgage with good terms. But her tenant score was 685 out of 1,000 — too low for her to rent an apartment without paying an elevated deposit. The screening company, LeasingDesk, said in an email that another month’s rent was required because her credit history and rent-to-income ratio were “unsatisfactory.”

Crawford, who uses a wheelchair, pleaded with a property manager to let her move in without the extra fee, showing paystubs proving she had made additional money by working overtime during the summer. The manager relented, allowing her to pay the base-rate deposit of $300.

She finished her two-year program and graduated with a Master of Fine Arts degree in 2020, never missing a rent payment before moving out early due to the pandemic. After she’d vacated, the apartment owners claimed she owed rent money for leaving before her lease was up.

“If they had just denied housing, I don’t know what I would have done,” she said. “Maybe I would have dropped out of the program.”

LeasingDesk’s parent company, RealPage, said it could not comment on individual cases, but that each LeasingDesk score is based on a property manager’s leasing criteria. RealPage applies those criteria “in an objective, consistent and non-discriminatory manner,” the company said in an emailed statement.

“In making leasing decisions, a property manager’s interest is not to turn away qualified applicants, but to quickly fill vacancies with people who will be responsible tenants and help maintain a safe community,” the statement said.

“What Is the Science Behind This?”

Credit reporting has faced more scrutiny over the years than tenant screening.

For instance, the big three credit bureaus — Equifax, Experian and TransUnion — stopped reporting evictions in 2017 after reaching multistate settlements in response to lawsuits that accused the firms of persistent mistakes in their reports. The companies denied wrongdoing. Tenant screening companies continue to report evictions.

Large numbers of consumer complaints can also help spur federal financial regulators to examine a credit scoring model, but no federal agency has the same power over tenant screening.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau collects complaints about tenant screening services, but it doesn’t examine the firms’ algorithms. The agency could not provide a breakdown of how many complaints have been filed regarding tenant screening agencies.

A spokesperson for the consumer bureau declined to respond to a list of questions from ProPublica, but said, “The Bureau is committed to using its tools and authority to ensure that consumers are not harmed by improper screening and consumer reporting practices.”

The Federal Trade Commission can’t examine a screening company’s algorithm unless it is doing a formal investigation. The agency, which has obtained multimillion-dollar settlements from such firms over errors in their reports, has not to date announced any enforcement actions stemming from bias in screening algorithms.

Asked about the agency’s oversight, Assistant Director Robert Schoshinski said: “We are always looking to see if there are violations of the laws that we enforce.”

The federal Fair Credit Reporting Act, which covers credit scores and background checks, has received few updates since it passed in 1970, said Eric Dunn, director of litigation for the National Housing Law Project. The problems tenants are encountering with screening, he said, are the result of an antiquated regulatory system that is full of gaps.

Dunn said some of the scoring models he’s seen while litigating cases on behalf of tenants are crude, giving so much weight to factors like eviction, criminal history or debt that a person whose record includes even one of those things would get a negative recommendation.

“For a lot of these companies, it’s a way of putting a veneer of legitimacy or a veneer of mathematical expertise on what’s really a blanket policy against people with certain types of records,” Dunn said.

Wu, of the National Consumer Law Center, echoed his concerns. “What is the science behind this?” Wu said. “With credit scoring, we know how well it works.”

In a letter to the CFPB in March 2021, Sen. Elizabeth Warren and five other senators wrote that screening companies need to be watched more closely. “Effective oversight of these companies requires proactively investigating and auditing their effects on protected classes,” the letter said.

The Consumer Data Industry Association, in a letter to the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs the following month, said screening is based on “race-neutral data” and removes subjectivity that could be a source of discriminatory behavior.

TransUnion, a credit agency that also offers tenant screening, said the system already receives scrutiny. “The rental screening process is well-regulated and governed by the Fair Housing Act and Fair Credit Reporting Act, with additional oversight from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau,” a statement emailed by a spokesperson said.

Screening firms are supposed to show tenants what’s in their files if they ask. The data industry association told the Senate committee that “tenant screeners facilitate consumer participation by providing copies of reports to consumers.” But firms have often interpreted the disclosure requirement narrowly, tenant advocates say, and left out key information — such as the recommendations made to landlords.

Tenants have less protection than job candidates, who are entitled to a copy of their background check if an employer is planning to reject them because of the report. That is supposed to give candidates time to look for errors. While landlords are supposed to provide tenants notice of an adverse screening result, like the one Kim Fuller in Baltimore received, such notices typically provide sparse information.

Dunn said tenants often get the runaround when they complain about screening decisions. The screening companies say landlords decide what criteria to use. Landlords say screening companies make the decision.

Several renters told ProPublica that they couldn’t find out why their applications were denied.

“You really have no effective way of lodging a dispute with the screening company, unless it’s the accuracy of the record,” Dunn said. “If it has anything to do with judgment, or anything like that, the screening company says, ‘It’s not our job.’”

Leaving the City

Fuller kept up her search for a new place for herself and her mother in Baltimore. She worried not only that her denial was a form of illegal redlining, but also that her full tenant screening report, which she never saw, contained errors that had pushed the algorithm toward a denial.

She filed a complaint with the CFPB against RentGrow, a subsidiary of Yardi Systems, one of the largest property management software companies in the United States. She also filed one against Habitat America.

The CFPB rejected both complaints last fall, saying it was “unable to send your complaint to the company for a response.” The agency said either the company was not in its complaint system or the agency does not handle complaints “about this product or issue.”

The CFPB accepts complaints about tenant screening companies, but property managers are beyond its purview. A CFPB spokesperson declined to comment on Fuller’s complaints.

Fuller widened her search for a new home. Her mother had lived for 35 years in the porch-front row house they shared on the edge of the Belair-Edison neighborhood. Though her mother had hoped to stay in Baltimore city, Fuller began looking in the suburbs.

A co-worker told her about an affordable complex near Catonsville, just outside the Baltimore Beltway. A Walmart was within walking distance. Fuller watched for vacancies at the aging brown brick cluster of three-story buildings and applied when she saw one.

She and her mother moved into a ground-floor unit in January.

“We had to go a little further out than we intended,” she said. “This will be an adjustment.”