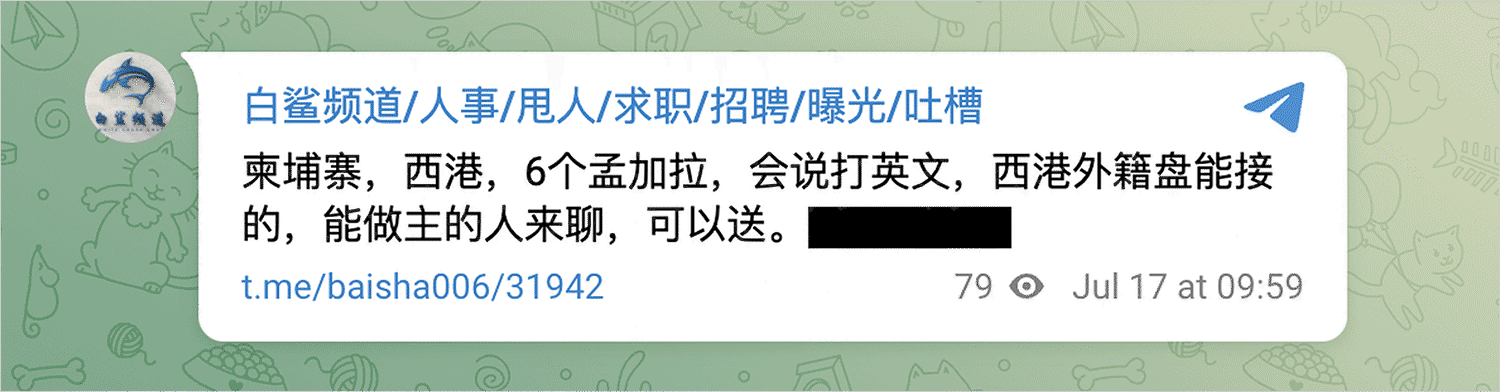

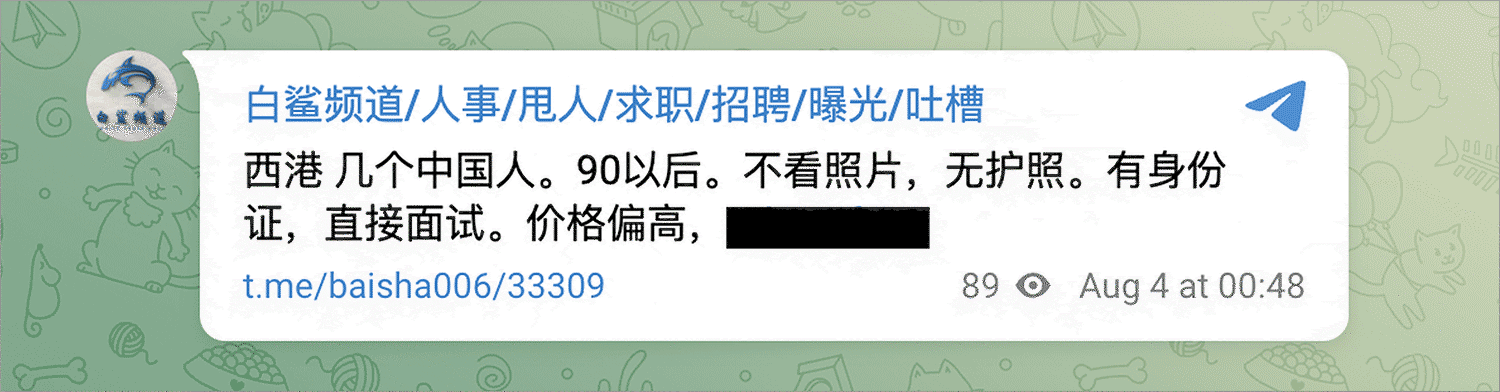

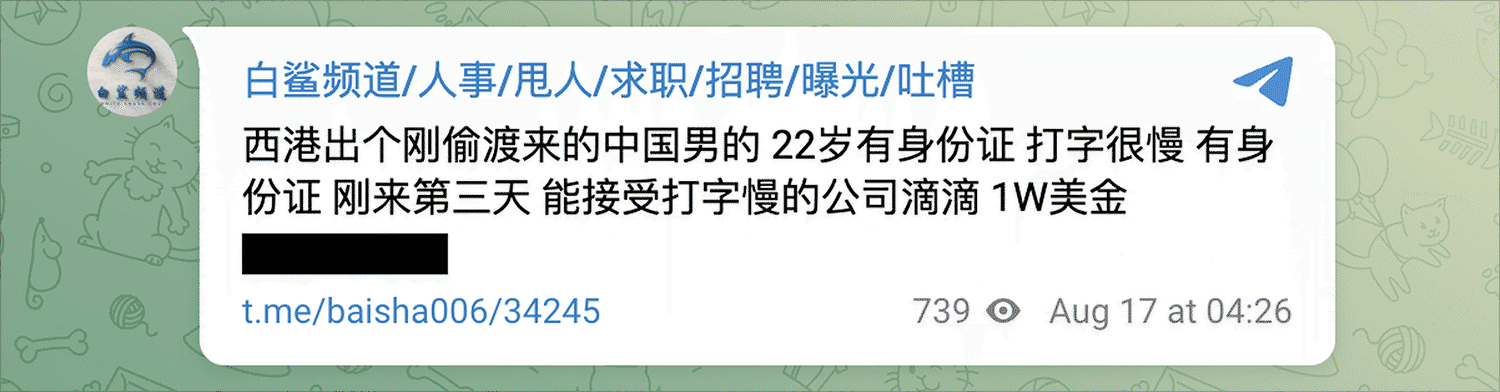

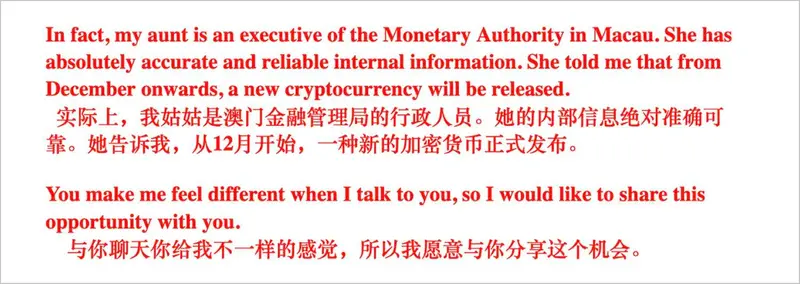

The ads on the Telegram messaging service’s White Shark Channel this summer had the matter-of-fact tone and clipped phrasing you might find on a Craigslist posting. But this Chinese-language forum, which had some 5,700 users, wasn’t selling used Pelotons or cleaning services. It was selling human beings — in particular, human beings in Sihanoukville, Cambodia, and other cities in southeast Asia.

“Selling a Chinese man in Sihanoukville just smuggled from China. 22 years old with ID card, typing very slow,” one ad read, listing $10,000 as the price. Another began: “Cambodia, Sihanoukville, six Bangladeshis, can type and speak English.” Like handbills in the days of American slavery, the channel also included offers of bounties for people who had run away. (After an inquiry from ProPublica, Telegram closed the White Shark Channel for “distributing the private information of individuals without consent.” But similar forums still operate freely.)

Fan, a 22-year-old from China who was taken captive in 2021, was sold twice within the past year, he said. He doesn’t know if he was listed on Telegram. All he knows is that each time he was sold, his new captors raised the amount he’d have to pay to buy his freedom. In that way, his debt more than doubled from $7,000 to $15,500 in a country where the annual per capita income is about $1,600.

Fan’s descent into forced labor began, as human trafficking often does, with what seemed like a bona fide opportunity. He had been a prep cook at his sister’s restaurant in China’s Fujian province until it closed, then he delivered meals for an app-based service. In March 2021, Fan was offered a marketing position with what purported to be a well-known food delivery company in Cambodia. The proposed salary, $1,000 a month, was enticing by local standards, and the company offered to fly him in. Fan was so excited that he told his older brother, who already worked in Cambodia, about the opportunity. Fan’s brother quit his job and joined him. By the time they realized the offer was a sham, it was too late. Their new bosses wouldn’t let them leave the compound where they had been put to work.

Unlike the countless people trafficked before them who were forced to perform sex work or labor for commercial shrimping operations, the two brothers ended up in a new occupation for trafficking victims: playing roles in financial scams that have swindled people across the globe, including in the United States.

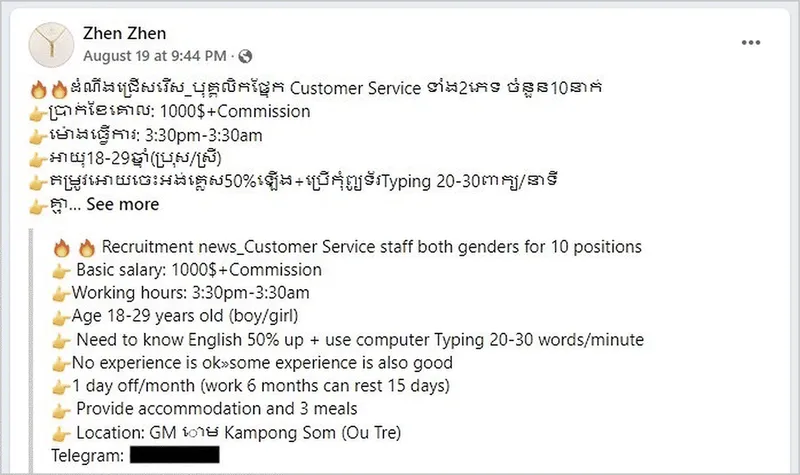

Tens of thousands of people from China, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam and elsewhere in the region have been similarly tricked. Phony job ads lure them into working in Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar, where Chinese criminal syndicates have set up cyberfraud operations, according to interviews with human rights advocates, law enforcement personnel, rescuers and a dozen victims of this new form of human trafficking. The victims are then coerced into defrauding people all around the world. If they resist, they face beatings, food deprivation or electric shocks. Some jump from balconies to escape. Others accept their lot and become paid participants in cybercrime.

Fan and his brother eventually ended up in Sihanoukville in a compound surrounded by a barbed wire fence. They were made to lure people in Germany into depositing funds with a phony online brokerage controlled by their operation, which also targeted English speakers in Australia and elsewhere.

“This idea of combining two crimes, scamming and human trafficking, is a very new phenomenon,” said Matt Friedman, chief executive of the Mekong Club, a Hong Kong-based nonprofit that combats what it calls modern slavery. Calling it a “double hurt,” Friedman said it’s unlike anything he’s ever seen in his 35-year career. The phenomenon has only just begun to come to light in the U.S., including in a Vice article published in July.

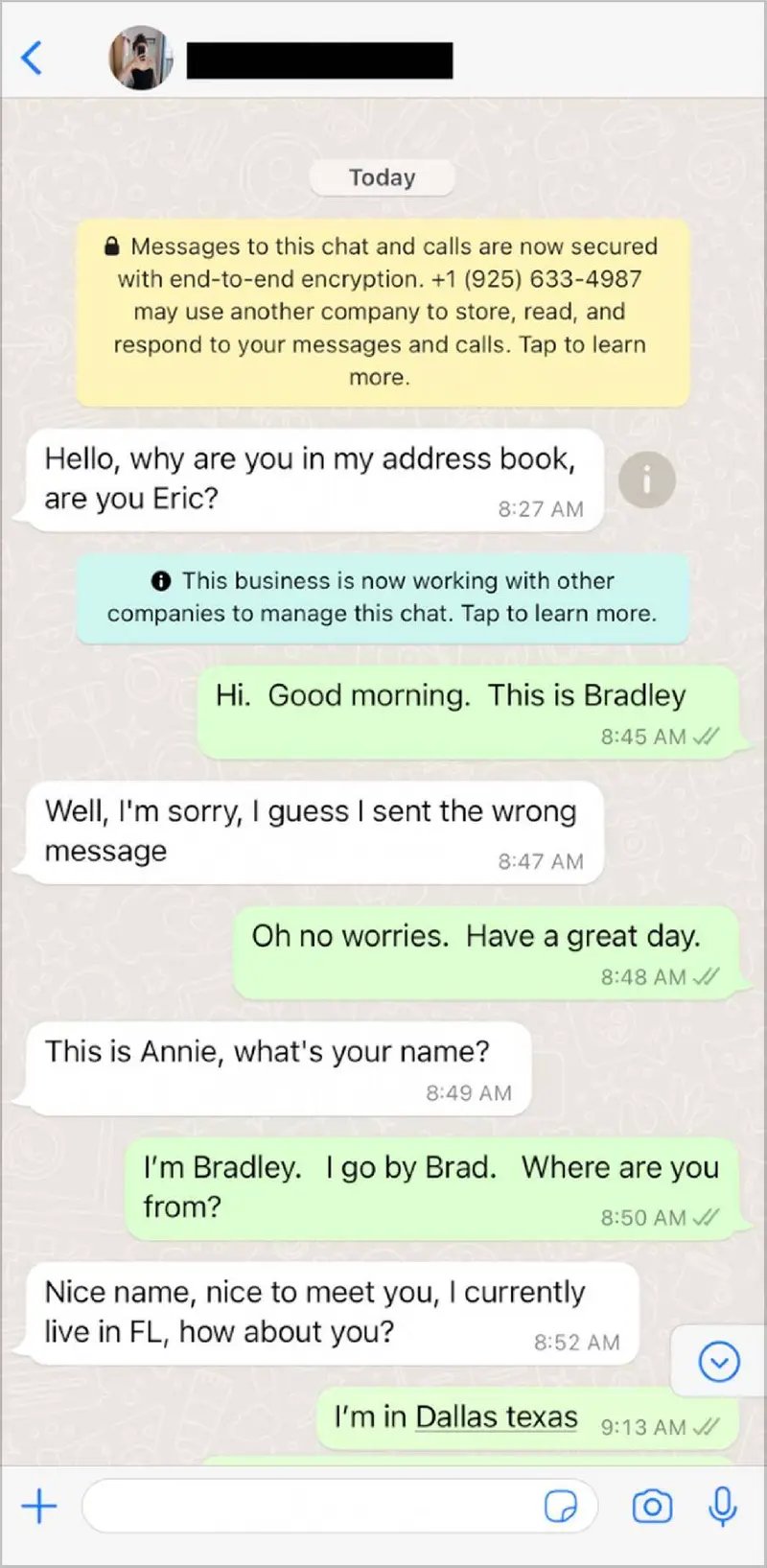

The most widely used technique among these operations is known as pig butchering, an allusion to the practice of fattening up a hog before slaughtering it. The approach combines some time-tested elements of fraud — such as gaining trust, in the manner of a Ponzi scheme, by making it easy for marks to extract cash at first — with elements unique to the internet era. It relies on the effectiveness of relationships nurtured on social media and the ease with which currencies can be moved electronically.

Typically, fraudsters ingratiate themselves into online friendships or romantic relationships and then manipulate their targets into depositing larger and larger sums in investment platforms that are controlled by the fraudsters. Once the targets can’t or won’t deposit more, they lose access to their original funds. They’re then informed that the only way to retrieve their cash is by depositing even more money or paying a hefty fee. Needless to say, any additional funds disappear in similar fashion.

Some Americans have lost huge sums. An entrepreneur in California said she was swindled out of $2 million and unwittingly facilitated an additional $1 million in losses by convincing her friends to join her in what seemed like a surefire investment. A hospital technician in Houston enticed her friends and colleagues to join her in a similar scheme, costing the group $110,000. An accountant in Connecticut is no longer preparing for retirement after watching $180,000 vanish in two separate swindles. They were among more than two dozen scam victims from seven countries interviewed by ProPublica.

Out of fear or shame, most pig butchering victims do not report their losses. That’s one reason that the limited data available likely understates the scale of the damage. According to the Global Anti-Scam Organization, a nonprofit founded last year to combat the new form of fraud, at least 1,838 people in 46 countries have lost an average of about $169,000 each to pig butchering since June 2021. Many still seem stunned by the effectiveness of the trickery. “I have to say, it’s brilliant,” said a Silicon Valley CEO who tallied her loss at $800,000 and asked not to be named out of embarrassment. For many victims, the betrayal by a seeming friend only compounds the devastation.

Fan’s ordeal began with a burst of optimism. He flew to Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh — it was his first time leaving China — and then waited out two weeks of COVID-19 quarantine in a hotel. He was then driven to a walled-off condominium complex in the city to begin his training. It was only then, in April 2021, that he realized something was off. Instead of learning about food delivery or working in a kitchen, he and his brother were placed in front of computers and told to study materials about how to defraud people online.

Fan, who is serious and reserved, with a crew cut and a round face that betrays little emotion, was able to document parts of his account, including the offer letter that drew him to Cambodia. (Fan is his family nickname; he asked that ProPublica not include his full name out of fear of his captors.) His experiences resembled those of other trafficking victims ProPublica interviewed and aligned with descriptions provided by experts and others.

Fan and his brother spent six months engaging in pig butchering schemes before their bosses decided to relocate the operation to Sihanoukville. The bosses presented them with a choice: They could pay the equivalent of $7,000 each to leave, or they could move along with the company. The brothers, who were paid negligible wages for their work, couldn’t afford the fee. So they relocated to Sihanoukville, in the upper floors of a hotel and casino called the White Sand Palace located in the center of the city.

The job could be terrifying. Fan said he witnessed a worker “half-beaten to death” by guards. “People were saying: ‘Help him! Help him!’” he recalled. “But nobody went up to help him. Nobody dared to.”

Only weeks after Fan and his brother arrived at White Sand, they experienced a brief moment of hope, Fan said. A person approached them and offered to get them out. With his help, they managed to leave — only to realize that the seeming savior had sold them to another criminal organization. This one was located in a fortified complex of beige dormitories on the edge of Sihanoukville with the grandiose name Arc de Triomphe. The $7,000 each owed for his freedom had risen to $11,700. And the price would go higher still.

Cyberfraud operations in Asia, including the ones Fan worked for, are highly organized. Some have gone so far as to draft detailed, psychologically astute training materials on how to dupe strangers. ProPublica obtained more than 200 such documents from an activist who helps involuntary workers escape.

Step one in the fraud process for Fan and others was to create an attractive online persona. In his case, he was expected to pose as a woman when wooing targets online. His operation bought photos and videos from websites that cater to such operations. For example, bundles of hundreds of photos of good-looking women and men are available for less than the cost of a cup of coffee from a shop called YouTaoTu. Another website markets a “pig butchering scam” package: For the equivalent of $12, it offers a “handsome guy set” of images of a man with perfectly chiseled abs. (Neither online store responded to requests for comment.) Such photos are frequently lifted from the online accounts of unsuspecting people; ProPublica found that images used by one fraudster were stolen from the Instagram profile of a Chinese social media influencer.

Scamming guides obtained by ProPublica recommend using such photos to set up social media accounts and then bolster them with the simulacrum of an affluent lifestyle by posting photos of luxury cars, along with descriptions of relevant hobbies such as investing. Stressing your belief in the importance of family, one guide adds, is the sort of touch that helps foster trust.

The resulting profiles can seem so real that one Canadian man met his future scammer after Facebook’s algorithm suggested the person to him as a friend. The chance encounter cost him and his friends nearly $400,000, according to a police report he later filed. Other victims told ProPublica they met their scammers on LinkedIn, OkCupid, Tinder, Instagram or WhatsApp. (Meta, which owns Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram, said it has “long prohibited this content” and is investing “significant resources” into blocking it. Match Group, owner of Tinder and OkCupid, said it’s using machine learning and content moderators to fight fraud. LinkedIn didn’t respond to emails seeking comment.)

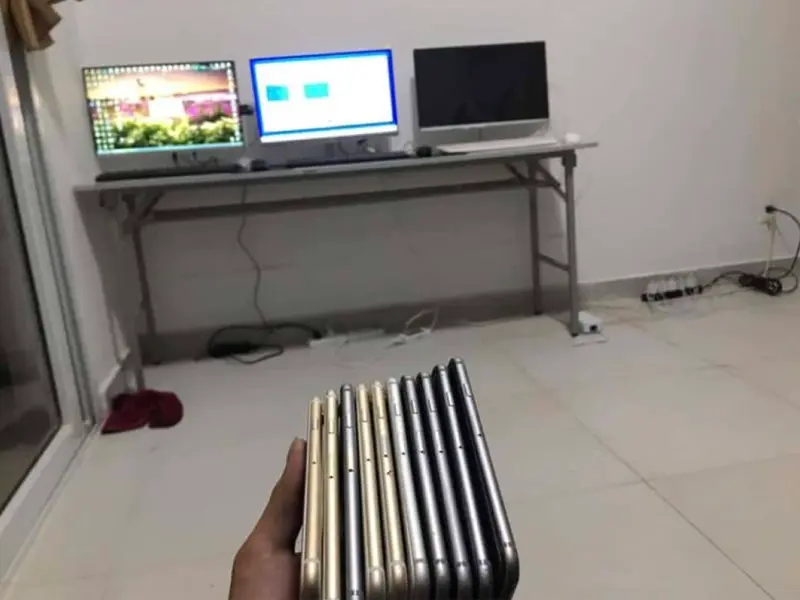

The next step for Fan was to contact as many victims as possible. He recalled working on a team of eight under a group leader, who gave each of them 10 phones to make it easy to keep multiple chats going, along with lists of phone numbers to contact. Fan’s job was to try to initiate conversations on WhatsApp. He would do it by pretending he had reached a wrong number, a common ruse. Others would open with a simple “Hi.”

Some tiny percentage of people responded favorably. When they did, Fan’s job was to handle the crucial initial part of the conversation. That’s when scammers are instructed to get to know their victims and discover what one training guide calls “pain points” that can be exploited. It’s also an opportunity to do what another document calls “customer mapping,” screening potential marks to glean information on their wealth and their vulnerability to being “cut,” slang for convincing them to fall for the scheme.

Using WhatsApp offered other practical advantages. Initially, Fan said, his team was aiming its efforts at Germans. Fan doesn’t speak a word of German, but it didn’t matter. All his chats were filtered through language translation software. Later, his team shifted to marks who spoke English. If any of the potential victims wanted to hear the voice of the attractive woman he was pretending to be, Fan said, there was a woman on staff who spoke fluent English and could record voice memos for him.

Because he was a rookie, Fan’s job was mostly limited to enticing marks to download an app called MetaTrader that would provide access to a brokerage where, he told his new “friends,” they could make fortunes trading cryptocurrencies. Fan would try to convince them to buy cryptocurrencies such as ethereum or bitcoin and deposit them in a brokerage controlled by the scam operation. The brokerage would then post phony numbers, including ones that represented supposed gains in their accounts.

If customers complied and began depositing significant sums, Fan said, he would typically hand the phone to his boss, who would take over and begin prospecting for a major strike. The strategy squares with what several scam victims told ProPublica: They sensed they were talking with multiple people. Indeed, they often were.

About 8,000 miles from Cambodia, an American who lives near San Francisco got a WhatsApp message on Oct. 7, 2021, from a stranger calling herself Jessica. She seemed to have reached him by mistake. Jessica asked the man, whose middle name is Yuen, if they knew each other; she said she had found his number on her phone and didn’t know why. Yuen responded that he didn’t know her. But Jessica was chatty and friendly, and her photo was alluring, so they kept talking.

Yuen agreed to tell his story on the condition that ProPublica identify him only by his middle name and omit certain details that could identify him. He saved his chat history with Jessica, which would run to 129,000 words over several months, and later shared it with ProPublica. (Yuen also shared his chat history with Forbes.)

At the moment Jessica initiated contact, Yuen was vulnerable. His father was in a hospital, dying from a lung disease. He had entrusted Yuen, the youngest of four siblings, with the power to decide whether to cut off his life support. It would also be up to Yuen to plan his father’s funeral and distribute his estate.

The family had immigrated to the U.S. from Hong Kong decades earlier. Yuen, who is in his early 50s and works as an accountant for a major university, was more affluent than his siblings, who are all older than him. He felt it was his duty to take care of them in old age, much as he was caring for his father and had cared for his late mother. Jessica told him she admired his commitment to his family. She shared her own tale of having a grandfather in the hospital.

Jessica was, by all appearances, a savvy and talented woman. She claimed to be a Chinese immigrant herself, a private banker at J.P. Morgan Chase in New York City. (A Chase spokesperson said the bank has no current employee with her purported Chinese name, Wang Xinyi.) Jessica’s photographs showed her spending weekends on Long Island playing with her rich friend’s toddler. She seemed fashionable, loved shopping and found time for yoga nearly every day, and she would flirt with Yuen. When Jessica posted photos of herself at a luxurious beach property, he wrote, “Wish I was there now.” She replied, “We can go play together.”

One Monday in late October, Jessica told Yuen she had just made $100,000 trading gold contracts. She let him in on a secret: She had a rich uncle in Hong Kong who had his own team of analysts who fed her inside quotes about where the price of gold would move. Every time “Uncle,” as she referred to him, called with news of where the market would go, she could make a guaranteed 10% profit by trading on his directions.

Jessica offered to teach Yuen — but only him. “Why just me?” he asked. Jessica said it was because she sympathized with Yuen about his dying father. “The money you earn can better help your father,” she explained. Plus, she knew she could trust him to keep her secret about insider trading. “Of course, I won’t tell anyone,” Yuen told Jessica as he pondered whether to join in.

The exchange marked a key moment in Yuen’s relationship with Jessica. The person behind Jessica’s alter ego was using a manipulation technique called “altercasting,” according to Martina Dove, a psychology researcher and author of “The Psychology of Fraud, Persuasion and Scam Techniques,” who reviewed Yuen’s chat log at ProPublica’s request. It puts the scammer in a position of trusting the target so that the target will reciprocate trust later on. Keeping the trading secret also meant less chance that Yuen’s wife or teenage daughter would learn about his chats with Jessica.

When Yuen agreed to put some money into gold, Jessica told him to download MetaTrader from Apple’s app store. She then told him to use the app to search for a brokerage called S&J Future Limited.

Yuen made it clear he couldn’t afford to lose any money. If he did, he said, he’d have to kill himself. Jessica said there was no need to worry: Uncle was never wrong. Yuen owed it to his father to seize the opportunity.

On Oct. 26, the day he had to go to the hospital to discuss his father’s end-of-life care, Yuen put money on the line for the first time. A conservative investor and lifelong saver, he’d been petrified to put even $2,000 into the brokerage. Jessica convinced him to start with $10,000 and taught him the two-step process to fund his account. First, he wired money from his bank to buy a cryptocurrency called ethereum. Then he could transfer the ethereum to a crypto wallet, whose address she provided.

Jessica insisted that using a cryptocurrency would help Yuen minimize his tax burden. He admitted he had very little idea of what he was doing. No matter. When the transfer was done, his S&J account reflected the deposit. And the next day, when Uncle called Jessica with news, Yuen was ready to buy. His account showed he made $746 after fees.

Jessica claimed she had made $500,000 on the same trade. She told him to get his account up to $50,000 to start earning meaningful sums. Yuen agreed and wired $20,000 the next day and another $20,000 a few days after that. When Jessica saw that he was doing as she’d directed, she praised him — “you’re smart” — and reminded him that the more money he put in, the more he’d earn for his father and siblings.

Little by little, Jessica encouraged Yuen to invest more and more. Yuen liquidated some mutual funds and wired nearly $58,000 on Nov. 2. When Uncle called with news later that night, his MetaTrader account showed an eye-popping gain of $17,000.

In those early weeks, Yuen was thrilled with Jessica. He called her his “true angel” in one message and offered up emojis of joy. Jessica wrote back: “I am not an angel, I am a demon.” She added two smiley-face emojis.

If Cambodia has a capital of fraud, it may well be Sihanoukville, which is named for the country’s onetime king who was ousted in an American-supported coup during the turmoil that erupted as the U.S. bombed the nation during the Vietnam War. The city has transformed over the past five years from a quiet beach resort to a metropolis of casinos and ghostly towers in various stages of construction or decay. The building boom was funded by Chinese investors, who started pouring millions of dollars into Sihanoukville after 2016, when the Philippines launched a crackdown on illegal online gambling outfits that were aimed at Chinese citizens. Cambodia had looser gaming regulations, and its government welcomed Chinese investment, making it a perfect substitute.

Soon Cambodia experienced the same influx of organized crime that had prompted the crackdown in the Philippines. Cambodia, under pressure from the Chinese government, announced a ban on online gambling in August 2019. Months after that, the COVID-19 pandemic struck and casinos in Cambodia were suddenly emptied of customers and workers.

Criminal syndicates repurposed their emptied real estate and began using it for scamming operations, according to Jason Tower, Myanmar country director for the United States Institute of Peace, and other observers in the region. “They’re criminal businesses, but they’re businesses at the end of the day,” he said. “So what did they do? They adapted.” And thanks to the pandemic, human traffickers found no shortage of job seekers with computer skills.

These facilities, which are housed in everything from office buildings to garish casino complexes, aren’t all tucked away in isolated neighborhoods. Some are prominently situated in the heart of cities. The White Sand Palace, which contains not only a gambling establishment but also multiple floors of fraud operations, according to former workers there, is located diagonally across the street from the summer residence of the Cambodian prime minister. White Sand didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Many fraud operations are surrounded by barbed wire fences. It’s routine to see windows and balconies completely enclosed by bars. In the Chinatown area of Sihanoukville, storefronts for a noodle shop and a barbershop look unexceptional, until you walk inside and notice that there are bars inside preventing anyone from exiting the complex of heavily guarded buildings.

Over the past year, an array of activists, journalists and nongovernmental organizations in Southeast Asia have begun revealing what’s going on behind the bars in these buildings. Ngô Minh Hiếu, a reformed hacker who now works as a cybersecurity analyst for the Vietnamese government, was one of the first to identify the sites. NGOs such as the International Justice Mission, as well as local media outlets, most notably VOD News, have revealed details of the operations. (ProPublica collaborated with three reporters affiliated with VOD to prepare this article.)

Others, such as Lu Xiangri, who became a volunteer rescuer after escaping a Sihanoukville scam sweatshop, have collected videos depicting abuses in these operations. Lu witnessed severe mistreatment when he was briefly detained inside the Arc de Triomphe last October: He saw a man with a broken leg and a bruised back begging to be sold so that he could avoid further beatings; Lu said the man later died of his injuries. Determined to help others avoid a similar fate, Lu joined a volunteer rescue team, which exposed him to a steady stream of pleas for help that often include graphic images of wounds left by electric shock batons and other corporal punishment. (ProPublica examined scores of similar photos and videos, some of which depict torture — including the use of electronic shock devices on workers’ genitals — but is publishing only a limited number whose authenticity was verified by Lu.)

Content Warning

The following images show the beating and torture of captive workers in Cambodia. Two photos depict partial nudity to show the extent of the bruising. ProPublica has obscured the faces of the victims.

ProPublica drove up to the gates of three compounds in Sihanoukville where people have alleged being detained and compelled to work as fraudsters. They included the Arc de Triomphe, one complex in Chinatown and another sprawling compound known as White Sand 2. Security guards at the three locations either denied that anything illegal goes on inside or refused to answer questions. “Talk to the boss,” one said, without specifying who the boss was.

Fan said his life was tightly circumscribed when he worked and lived inside the Arc de Triomphe compound. He could leave his building and enter an adjoining casino and karaoke bar — he said he had no interest, though some workers did gamble or go to the karaoke bar — but the presence of guards would dissuade any hopes of going out into the street. During the four months he was at the Arc de Triomphe, he said, he never set foot outside the compound.

His schedule and routine were regimented. Fan worked on the second floor of a building from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m., then again from 11 p.m. to 5 a.m. He slept in a dorm room with metal bunk beds, with four or five people per room. There was even a small clinic in the compound that provided first aid and rudimentary medical treatment. As Fan put it: “You can’t go anywhere. You’re either eating, sleeping or working.” The days ran into each other, and Fan tried to anesthetize his own feelings, willing himself into emotional torpor. His only pleasure came from playing a fantasy warfare game on his phone each night before going to bed.

Fan hated the work. Cheating people out of money was the last thing he thought he’d be doing when he answered a job ad. But he couldn’t leave the compound, nor could he afford to buy his way out. His bosses at the Arc de Triomphe demanded $23,400 for him and his brother. The two were essentially paid on commission, which meant that the more he wanted his freedom, the more he’d have to bilk.

In part because he would hand over promising targets to his boss, but perhaps also because of his reluctance, Fan never delivered a big score. The most he landed was $30,000. He said he felt so terrible after that “success” that he deleted the victim’s contact information from the organization’s database to make sure the person couldn’t be further stripped of cash. Others on his team, he said, extracted as much $500,000 from a single victim.

On Nov. 3, as Jessica was helping him turn his newest deposit of $70,000 into cryptocurrency, Yuen got a message that his father had been taken to the hospital. Yuen raced to join him, and as he sat in the waiting room, some other news came through. It was Jessica, saying her uncle in Hong Kong had given her another signal to trade.

Yuen explained to Jessica that his father was dehydrated and losing the will to eat. He was back in the hospital two days later, crying as he wiped his father’s hands and face. Shortly after, Jessica messaged to ask if his latest deposit of $20,000 had gone through. Yes, he said. He added that he’d decided to give his father comfort in his dying days by moving him to a hospice.

Jessica didn’t seem to grasp what a hospice was. When Yuen explained that it was a care facility for the terminally ill, she perked up: “You need to make more money.” Jessica told him he should raise his account balance to $500,000 so he could cover the cost more easily.

Over the next nine days, Yuen cashed in a $20,000 CD that his mother had bequeathed him and his siblings and tapped a dormant home equity line of credit for $200,000. Each time he traded with Jessica, his account showed an increase, and soon he surpassed the $500,000 mark she’d set out for him.

Yuen’s father died in the early morning hours of Nov. 14. Yuen was the only one with him when he breathed his last. He wrote Jessica, seeking sympathy, but got a perfunctory response. This is a common stratagem, said Dove, the psychology researcher. She calls it “scarcity”: withdrawing attention unless the target is doing what the scammer wants. When Yuen wanted to talk about anything related to money, Jessica engaged. When he wanted her attention for anything else, she was distant and tried to steer the conversation back to investing.

The next day, with his father now gone, Jessica gave Yuen another goal. She bragged that she was buying yet another home in New York. The conversation turned to real estate and how Yuen could afford a pied-à-terre there. Why, he asked? “So that we can get very close,” Jessica responded. She explained that Uncle had told her a “big market” was coming soon. “If you want to buy a house in New York, you need to increase your capital,” she said.

In just a few weeks of trading, Yuen had shed much of his previous caution. But now he resisted. He was planning his father’s funeral, he told Jessica, and he was overwhelmed at work. Buying a home in New York would have to wait. Jessica urged him to take out another loan. When Yuen refused, she chided him: “You are a wise man, this is borrowing a chicken to lay eggs.” But Yuen didn’t budge.

By Nov. 18, he had gone six days without depositing more money into his account. That’s when his investing idyll came to an end. That day, his MetaTrader app suddenly closed him out of his positions. By the time it was over, his account showed a balance of minus $480,000.

Yuen panicked. He couldn’t lose any of this money, but he felt he couldn’t turn to anyone for help, either. He’d been keeping his MetaTrader habit secret. He lied to his wife and daughter when they asked who he was messaging so frequently, brushing it off as an endless stream of work requests. His siblings didn’t know either. No one knew. No one except Jessica.

Jessica convinced him it was his fault. He must have exited the MetaTrader app instead of following her directions. But it was OK, she said. The big market was still there and he could make everything back quickly. “Prepare the funds and earn them back,” she said.

Yuen didn’t know it, but he had now entered the final stage of pig butchering. This is when scammers sense that their targets have been squeezed dry and are unlikely to deposit more funds. They then shift to the final manipulation: Making the targets aware that they’ve lost all their money and offering them a seeming lifeline to earn it back. The move aims to heighten the targets’ distress. “We normally don’t make our best decisions when we’re in a state of emotional arousal,” said Marti DeLiema, a gerontologist at the University of Minnesota who researches how older Americans are swindled.

Yuen immediately dialed up the financial institutions that managed his family’s savings and ordered a sale of $500,000 worth of mutual fund shares. As he waited for the money to be transferred, he debated whether to inform his family about the loss. Jessica told him, via an emoji depicting an index finger over closed lips, not to say a thing. If he’d only wait a few more days and deposit more funds, he’d turn his loss into a gain. “Yes, we will earn it back,” Yuen said.

The following week, Yuen borrowed $100,000 from his brother-in-law and resumed trading with Jessica as he made final preparations for his father’s funeral. On the day of the funeral, he messaged Jessica. “When I was crying today,” he wrote, “I wasn’t sure if I was crying because I lost my father or I lost all the money.” She responded, “Money can be earned, but people are gone if they are gone.” Yuen thanked Jessica for her help.

Midway through the following week, Jessica pushed him to borrow even more, but Yuen said he had no one he could turn to. Jessica wasn’t buying it. “I don’t think you’ve reached your limit,” she said, adding that every time she had asked him to gather cash before, he’d been able to do so.

When she pushed him again the next day, Yuen exploded. “Omg.!!!” he wrote. “You don’t understand! I have no more resources to get anymore money!” By that time, he couldn’t sleep or eat or do anything other than worry about how to make back his losses.

On Dec. 3, at 11:31 a.m., Jessica messaged Yuen to get ready to do another trade with Uncle’s news. Three minutes later, Yuen executed his 23rd trade with Jessica. Once again, disaster struck: All of his positions suddenly got closed, and his entire portfolio vanished as he watched.

Yuen convulsed with panic. He spent the next several hours in shock and terror as the consequences of the loss raced through his mind. “Give me a solution,” he begged Jessica. She told him to put more money in. When he told her that all he had left was $105, Jessica answered: “With $105, start from scratch, I believe you, you can do it.”

Later that day, Yuen confessed to his family. He told his wife he’d lost 30 years’ worth of their savings. He later admitted that the money he’d borrowed from her brother and the bank was also gone. In all, he had lost just over $1 million. Yuen asked his brother to call an ambulance to escort him to a psychiatric ward, where he was placed on a suicide watch.

Yuen was released two days later and spent December wondering what had happened. Jessica stopped replying to his messages after a few days, but he kept on asking. “It’s Christmas. Hope you have the heart to help me!!!” he messaged on Dec. 25. (ProPublica got no response to messages it sent to the WhatsApp number used by Jessica.)

Yuen said he didn’t accept that he’d been cheated until after Jan. 1. It was only through the intervention of close friends and relatives that he acknowledged what had happened. He found a support group, the Global Anti-Scam Organization, and began piecing together details of the scam, like a Reddit post warning that S&J Future Limited was a sham brokerage. A fellow victim set up a GoFundMe page to help him, and others began to chip in, including a Massachusetts woman who had lost $2.5 million herself.

But Yuen still struggled to comprehend what kind of person — and where? — would impose such suffering on someone else. He got a partial answer on March 31. That’s when Jessica contacted him again using a different phone number. Yuen was prepared: Another GASO member had taught him a trick to track down a person’s IP address to figure out their location. The chat log shows Jessica fell for the ruse. When the IP information came back, Yuen said, it indicated Cambodia.

Well before then, Fan and his brother had passed the point of desperation. They began seeking ways out of the Arc de Triomphe. In late January, Fan messaged the governor of Preah Sihanouk province via Facebook. The governor’s office responded, asking for Fan’s phone number, he said, and soon after the police called.

But the attempt backfired. Fan’s bosses found out about the call and summoned him and his brother. They berated the two for tarnishing the company’s reputation and threatened legal consequences, according to Fan. The meeting culminated in a videotaped confession in which Fan’s brother read a statement, on behalf of both brothers, prepared by their bosses. A video recording shows Fan’s brother reading a script in which he stated that they had gotten a “personal loan” from the company and had to repay it. He ended by saying, “We would like to apologize to the provincial governor.”

When Fan returned to his desk, his boss was furious. The boss slapped him, Fan said, threw a water bottle in his face and told him to go find the money to pay for his freedom. His boss warned him, according to Fan, that “it doesn’t even matter if you die in here” because it would be so easy to kill him. No one would care. (At least six dead bodies have been discovered in the marshlands or beaches near Sihanoukville’s scam compounds, many of them Chinese men.)

Fan’s police report turned him and his brother into troublemakers in the eyes of their employer. They got sold to another fraud operation, this one back in Phnom Penh, which tacked on further charges to their debt. Each now would have to pay $15,500 for his freedom.

In February, Fan found a way to get out. He noticed that his new bosses were less strict about security than his previous captors. They occasionally allowed workers to venture outside the compound. So Fan came up with an excuse — visiting a friend — and received permission to leave. He suspects that his captors let him go because they believed that, as long as they still held his brother, he would return.

But Fan didn’t return. Meanwhile, his brother called the police, and this time they came through. He was released at the urging of local authorities. But before his brother left, he was forced to confess again, this time in writing. That handwritten letter, which Fan shared with ProPublica, stated that he had borrowed $31,000 from the company, was happy and working voluntarily and had never been kidnapped or beaten.

Fan spent his first months of freedom in the Great Wall Hotel, a modest five-story guesthouse steps away from Phnom Penh’s airport that has become a haven for Chinese scam workers who manage to escape. Life at the Great Wall was safe but monotonous. Most residents were just passing the time as they waited for an opportunity to return to China, which has restricted travel due to its zero-COVID-19 policy. Those limits contributed to rising costs for airline tickets, putting a return nearly out of reach for many of the escapees.

In June, Fan moved out of the Great Wall Hotel. He declined to reveal his exact whereabouts, as he’s still afraid that he will be abducted by bounty hunters. Fan has obtained paperwork that will allow him to return to China without his passport, which a scam compound still holds, and his father recently managed to cobble together enough money to pay for him to fly home. Fan dreams of returning to work on his family’s farm, tending to ducks and chickens while safely under his parents’ roof. “I won’t come out to work again,” Fan said. “There’s not much future working for other people.”

Cambodia’s fraud operations often have links not just to organized crime but also to the country’s political and business elites. The Arc de Triomphe, for instance, is owned by K99, a real estate and casino junket operator led by Rithy Raksmei, brother of the late tycoon Rithy Samnang. Samnang was also son-in-law to ruling party senator Kok An, whose business empire includes properties that have faced allegations of forced scam labor. And the complex in Chinatown has a hotel that is part-owned by Xu Aimin, a Chinese fugitive who was sentenced to 10 years in prison for masterminding an illicit international gambling ring. (None of these individuals or entities have been prosecuted for involvement in Cambodian scam compounds and none responded to ProPublica’s requests for comment.)

In July, the U.S. State Department downgraded Cambodia to the lowest tier on its annual assessment of how well countries are meeting standards for eliminating human trafficking. The department asserted that Cambodian authorities “did not investigate or hold criminally accountable any officials involved in the large majority of credible reports of complicity, in particular with unscrupulous business owners who subjected thousands of men, women, and children throughout the country to human trafficking in entertainment establishments, brick kilns, and online scam operations.” A United Nations special rapporteur on human rights in Cambodia put it in searing terms in an August report: Workers trapped in Cambodian scam compounds are experiencing a “living hell.”

The day the U.N. report appeared, Cambodia’s government reversed months of denials and acknowledged that foreign nationals have been trafficked to the country to work in gambling and scam operations. Cambodian Interior Minister Sar Kheng condemned what he called “inhumane acts” and expressed regret. The statement came only days after a dramatic, widely seen video emerged of some 40 Vietnamese men and women breaking out of a reported fraud compound and, chased by baton-wielding men, frantically jumping into a river that divides Cambodia from Vietnam.

Cambodia’s senior official working to combat human trafficking, Chou Bun Eng, told ProPublica in a July interview that her government was still figuring out how to respond to scam sweatshops. “This is new for us,” she said. Top officials from Cambodian police, immigration and other government agencies met in Phnom Penh in late August to discuss a strategy. They pledged action, then almost immediately, the government’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation undercut that stance by releasing a statement in September asserting that human trafficking in Cambodia is “not as serious, bad as reported.”

Lacking any form of legally recognized status, escapees from scam compounds are left at the mercy of Cambodian police, who often treat them as illegal immigrants or criminals. Rescued people frequently end up in crowded immigration detention centers, sleeping on the floor in tight quarters without any air conditioning, according to images shared by a detainee.

The police have sometimes pursued the rescuers. Chen Baorong, the former head of a charity group that helped human trafficking victims escape, was arrested in February and charged with incitement. In late August, he was sentenced to two years in prison. Lu Xiangri, the volunteer rescuer, took up Chen’s mantle after his arrest, only to himself flee Cambodia in July out of concern for his safety. In response to questions from ProPublica, Cambodia’s General Commissariat of National Police wrote that “it is not the government policy to collude with any criminal group or facilitate the use of Cambodian soil by criminals as a hotbed for fraudulent activities overseas.”

The governments of China, Indonesia, Pakistan, Thailand and Vietnam have issued warnings in recent months about high-salary job offers emanating from Cambodia. Authorities in Taiwan and Hong Kong have gone so far as to station workers at airports to question people emigrating for work and to warn them about overseas employment scams. Still, even as the governments issue warnings about Cambodia, new operations are gravitating to places like Myanmar, where the violent aftermath of a military coup has created an opportunity for criminal syndicates to expand.

In the U.S., law enforcement and victims are trying, against long odds, to recapture lost money. In May, the Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Office seized $318,000 of stolen crypto funds on behalf of one pig butchering victim. Erin West, the deputy district attorney spearheading the effort, said her team has been able to seize an additional $233,000 since then and has a few more seizures in the works. Still, most funds aren’t recovered, and the chances drop rapidly as time passes.

Yuen is losing hope that he’ll recover his funds. At one point, he turned down an offer from a self-described hacker to introduce him to an FBI agent who would track down his stolen funds if Yuen paid him $5,000. Cautious, Yuen asked to see a photograph of the agent’s FBI identification. The badge looked authentic, as did the photo ID. But under the photograph, Yuen noticed the signature. It read “Fox Mulder,” the name of the fictional detective on “The X-Files.”

Mech Dara and Danielle Keeton-Olsen contributed reporting from Cambodia, and Salina Li from Hong Kong.