ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week. This story was co-published with the Chicago Tribune.

Top Illinois officials agreed last year that police shouldn’t ticket students for minor misbehavior at school and pledged to make sure it didn’t happen anywhere in the state. But a bill to end the widespread practice fizzled this spring because of disagreement over whether it would accomplish its goal and confusion about whether police would still be able to respond to crime on campus.

Now, legislators and activists are regrouping with a goal of rewriting the bill and passing it in the next legislative session. They say they are committed to changing state law because not all school districts complied when the Illinois State Board of Education superintendent implored them to stop working with police to issue municipal citations for noncriminal matters — tickets that can lead to fines of up to $750.

The push for change followed publication of “The Price Kids Pay,” a 2022 investigation by ProPublica and the Chicago Tribune that revealed how school-based ticketing was forcing families into a quasi-judicial system with few protections that sometimes landed them in debt. A state law already bans school officials from fining students directly, but administrators instead have been cooperating with police, who issue citations for violating local ordinances. The proposed legislation aimed to shut off that option.

In addition to the former state school superintendent’s strong stance, Gov. J.B. Pritzker said last year that he wanted to “make sure that this doesn’t happen anywhere in the state.” His spokesperson said Monday that his position has not changed. Current state Superintendent Tony Sanders also said he backs legislation to prevent ticketing. That support gives hope to the legislators pushing for change.

“We are going to get it done. We are in the process now of really fine-tuning it,” said state Rep. La Shawn Ford, a Democrat from Chicago and the bill’s chief sponsor. The bill passed the House education committee in March, but it was not called for a vote in the full chamber before the legislative session ended in late May.

Ford’s bill would have made it illegal for schools to involve the police in order to fine students for violating local ordinances — such as by vaping or fighting — when that behavior could be addressed through the school’s disciplinary process instead. School officials could still call law enforcement for criminal matters, and schools could still seek restitution from students for lost, stolen or damaged property. But some legislators voiced concerns that the bill might unintentionally limit when police can get involved in more serious incidents.

“There were some issues that came up that needed some clarity, and we felt it was better to continue to work on the language so we could get the best bill possible without unintended consequences,” Ford said.

Ford said he remains committed to making sure that families aren’t punished financially for student misbehavior in schools. “Anything that drives poor people further into poverty shouldn’t be a part of our school environment,” he said. “If a student has to choose between paying a fine and eating breakfast, that is a problem.”

Some districts stopped or cut back on referring students to police for minor disciplinary matters in the wake of “The Price Kids Pay,” but without a law preventing the tactic, others have not. Students across the state continue to get costly tickets for noncriminal infractions including having vape pens, fighting at school and engaging in other adolescent behavior that some say would be better handled by school officials, not the police.

Reporters also found that students in some towns, including Manteno, McHenry and Palatine, are still appearing before hearing officers to receive punishments from their municipalities for their school-based behavior. The consequences, including fines, often were levied in addition to school discipline the students had already received.

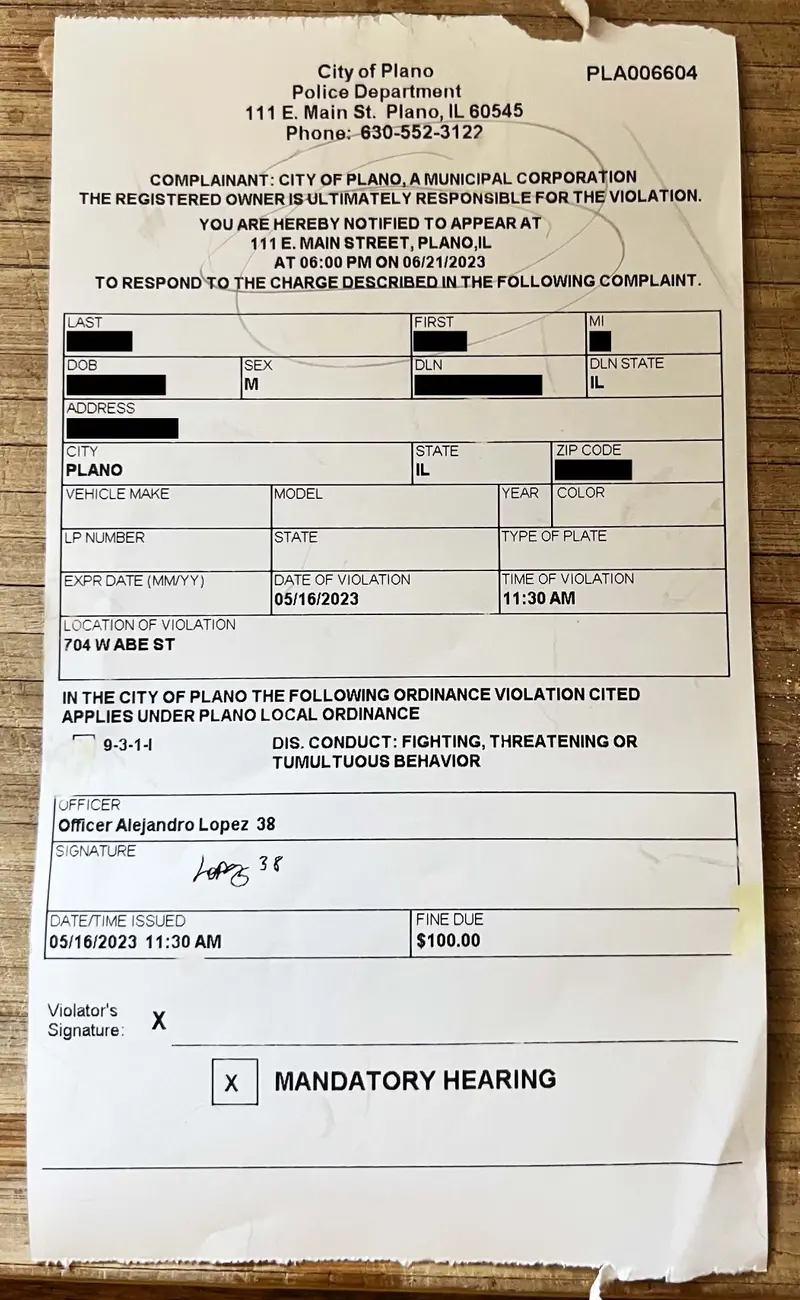

Last week, at the Plano Police Department about 60 miles west of Chicago, three teenage boys appeared before a hearing officer with $100 tickets they had received for a fight during a basketball game in gym class at Plano High School. The city’s school resource officer had issued the tickets after watching a video of the fight, according to a police report read at the hearing.

Two of the boys were accompanied by their mothers as they were sworn in and explained that they had acted in self-defense after another student started the fight.

The parents were upset about the tickets. One mother said in an interview that she knew the state superintendent had asked schools to stop working with police to ticket students, and her son had already been suspended for 10 days, which was punishment enough in her eyes.

“Everything is monetary now. It is like, ‘You do this wrong, you give us money.’ It isn’t teaching anything,” she said, adding that the school has denied her requests for a recording of the fight. “These little towns, even bigger towns, feel like they are untouchable.”

“I guarantee you that 90% of people have no clue that it isn’t supposed to be happening.”

The two students who said they had acted in self-defense were found not liable and did not have to pay fines. The third student, who recently graduated, pleaded liable and handed over $100 cash before leaving the police station. Their cases were the only three heard that night at the city’s “adjudication courtroom” in the Police Department basement.

Plano police Officer Alejandro Lopez, who issued the citations and supports ticketing as a consequence for students, said Plano High School students have received 26 tickets during the past two school years, primarily for disorderly conduct ($100 fine) and possession of cannabis ($250 fine). “It teaches them a lesson to not do it anymore,” Lopez said in an interview.

Lopez said he typically learns about the behavior from a dean or other administrator and then decides whether to issue a ticket.

That’s the process that the stalled legislation would have addressed by amending the state’s school code to make it illegal for school personnel to involve police for the purpose of issuing students citations for incidents that can be addressed through a school’s disciplinary process.

But legislators and advocates were concerned that interrupting that police referral process might not always prevent students from getting municipal tickets.

There also was apprehension among school officials that they could be accused of violating the school code if a police officer chose to ticket a student, even if that’s not what the school intended. The Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police opposed the proposed legislation.

Those in favor of ending school-based ticketing said they’re also exploring whether, rather than targeting policy change at the schools, a bill should instead focus on the municipalities because they’re the ones who oversee police officers in schools and determine penalties for ordinance violations.

“The real goal is to eliminate monetary penalties, municipal tickets for noncriminal school-based behaviors,” said Aimee Galvin, the government affairs director for Stand for Children Illinois, which helped draft the legislation, along with the Debt Free Justice Illinois Coalition. She said advocates will be meeting this summer and fall to explore new legislation that would be introduced next year.

“We are very upset that this is still happening. Our hope is the practice has decreased given the attention and ISBE’s direction, but we would love to see some legislation to right this wrong.”

Rep. Michelle Mussman, a Democrat from the Chicago suburb of Schaumburg who serves as chair of a House education committee, said lawmakers previously banned fining students at school because they thought that monetary punishments weren’t appropriate.

Legislators, she said, seem willing to close the loophole that emerged on fines and ticketing. “The problem is we haven’t figured out how,” Mussman said.

The legislature did pass a bill that, if signed by the governor, will eliminate most fines and fees in juvenile court. Young people who commit juvenile offenses would then be protected from monetary penalties, but that protection wouldn’t apply to those found to have violated municipal laws.

For their investigation, ProPublica and the Tribune documented about 12,000 tickets written to students over three school years and also found that, in places where information was available on the race of ticketed students, Black students were twice as likely to be ticketed as their white peers. (Use our interactive database to look up how many and what kinds of tickets have been issued in an Illinois public school or district.)

In Chicago’s northwest suburbs, District 211 and Palatine are the subject of an ongoing civil rights investigation launched by the Illinois attorney general’s office after “The Price Kids Pay” was published.

School district officials in Plano, Palatine, McHenry and Manteno did not respond to requests for comment for this story.