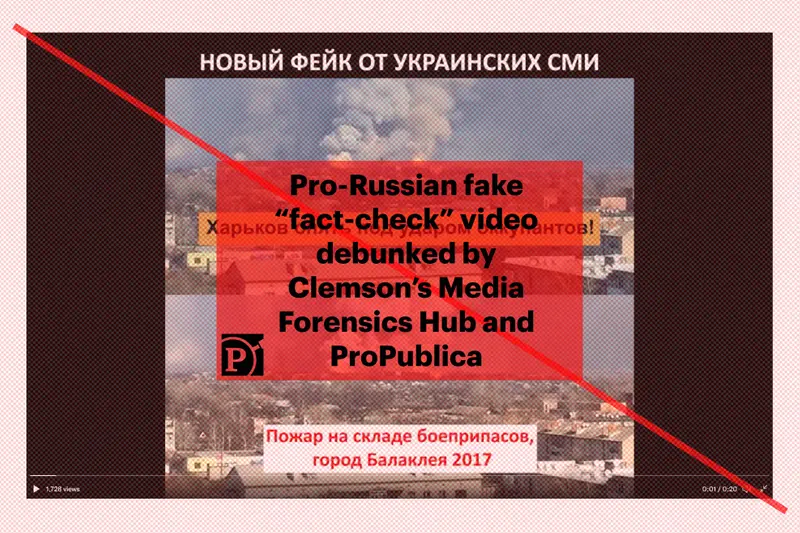

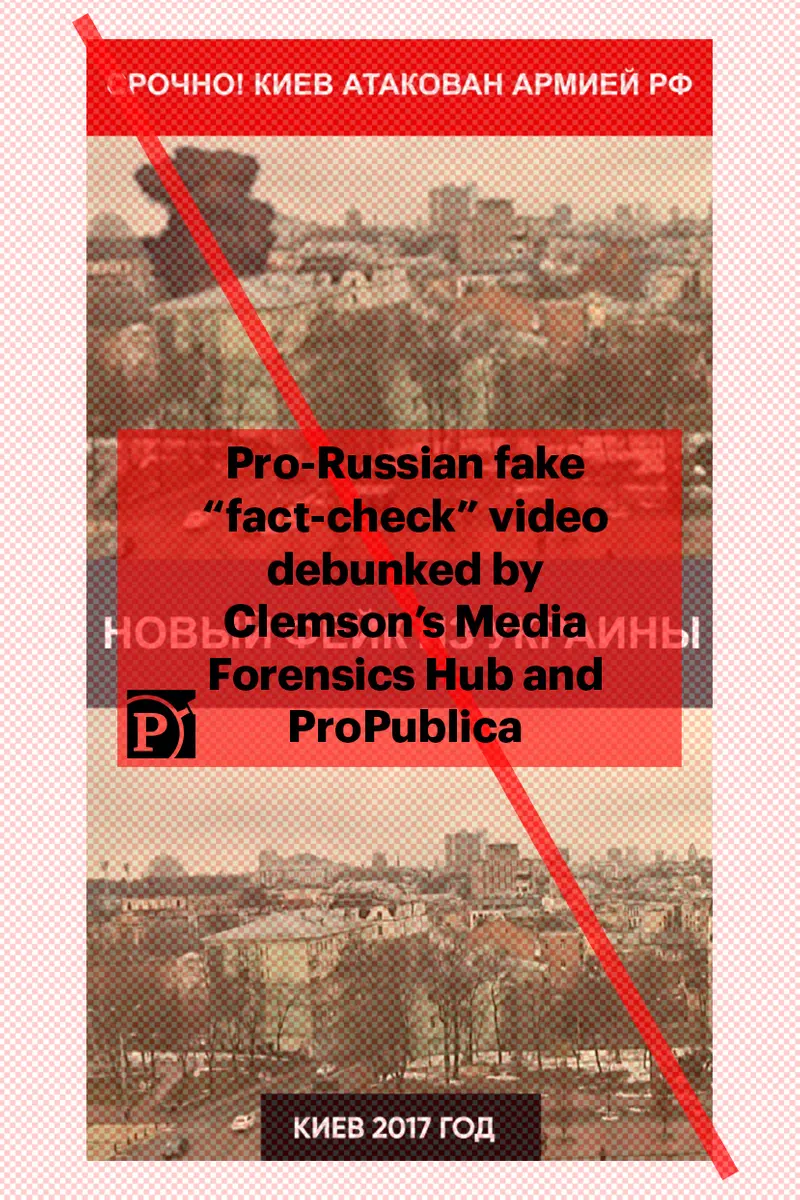

On March 3, Daniil Bezsonov, an official with the pro-Russian separatist region of Ukraine that styles itself as the Donetsk People’s Republic, tweeted a video that he said revealed “How Ukrainian fakes are made.”

The clip showed two juxtaposed videos of a huge explosion in an urban area. Russian-language captions claimed that one video had been circulated by Ukrainian propagandists who said it showed a Russian missile strike in Kharkiv, the country’s second-largest city.

But, as captions in the second video explained, the footage actually showed a deadly arms depot explosion in the same area back in 2017. The message was clear: Don’t trust footage of supposed Russian missile strikes. Ukrainians are spreading lies about what’s really going on, and pro-Russian groups are debunking them. (Bezsonov did not respond to questions from ProPublica.)

It seemed like yet another example of useful wartime fact-checking, except for one problem: There’s little to no evidence that the video claiming the explosion was a missile strike ever circulated. Instead, the debunking video itself appears to be part of a novel and disturbing campaign that spreads disinformation by disguising it as fact-checking.

Researchers at Clemson University’s Media Forensics Hub and ProPublica identified more than a dozen videos that purport to debunk apparently nonexistent Ukrainian fakes. The videos have racked up more than 1 million views across pro-Russian channels on the messaging app Telegram, and have garnered thousands of likes and retweets on Twitter. A screenshot from one of the fake debunking videos was broadcast on Russian state TV, while another was spread by an official Russian government Twitter account.

The goal of the videos is to inject a sense of doubt among Russian-language audiences as they encounter real images of wrecked Russian military vehicles and the destruction caused by missile and artillery strikes in Ukraine, according to Patrick Warren, an associate professor at Clemson who co-leads the Media Forensics Hub.

“The reason that it’s so effective is because you don’t actually have to convince someone that it’s true. It’s sufficient to make people uncertain as to what they should trust,” said Warren, who has conducted extensive research into Russian internet trolling and disinformation campaigns. “In a sense they are convincing the viewer that it would be possible for a Ukrainian propaganda bureau to do this sort of thing.”

Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine unleashed a torrent of false and misleading information from both sides of the conflict. Viral social media posts claiming to show video of a Ukrainian fighter pilot who shot down six Russian planes — the so-called “Ghost of Kyiv” — were actually drawn from a video game. Ukrainian government officials said 13 border patrol officers guarding an island in the Black Sea were killed by Russian forces after unleashing a defiant obscenity, only to acknowledge a few days later that the soldiers were alive and had been captured by Russian forces.

For its part, the Russian government is loath to admit such mistakes, and it launched a propaganda campaign before the conflict even began. It refuses to use the word “invasion” to describe its use of more than 100,000 troops to enter and occupy territory in a neighboring country, and it is helping spread a baseless conspiracy theory about bioweapons in Ukraine. Russian officials executed a media crackdown culminating in a new law that forbids outlets in the country from publishing anything that deviates from the official stance on the war, while blocking Russians’ access to Facebook and the BBC, among other outlets and platforms.

Media outlets around the world have responded to the onslaught of lies and misinformation by fact-checking and debunking content and claims. The fake fact-check videos capitalize on these efforts to give Russian-speaking viewers the idea that Ukrainians are widely and deliberately circulating false claims about Russian airstrikes and military losses. Transforming debunking into disinformation is a relatively new tactic, one that has not been previously documented during the current conflict.

“It’s the first time I’ve ever seen what I might call a disinformation false-flag operation,” Warren said. “It’s like Russians actually pretending to be Ukrainians spreading disinformation.”

The videos combine with propaganda on Russian state TV to convince Russians that the “special operation” in Ukraine is proceeding well, and that claims of setbacks or air strikes on civilian areas are a Ukrainian disinformation campaign to undermine Russian confidence.

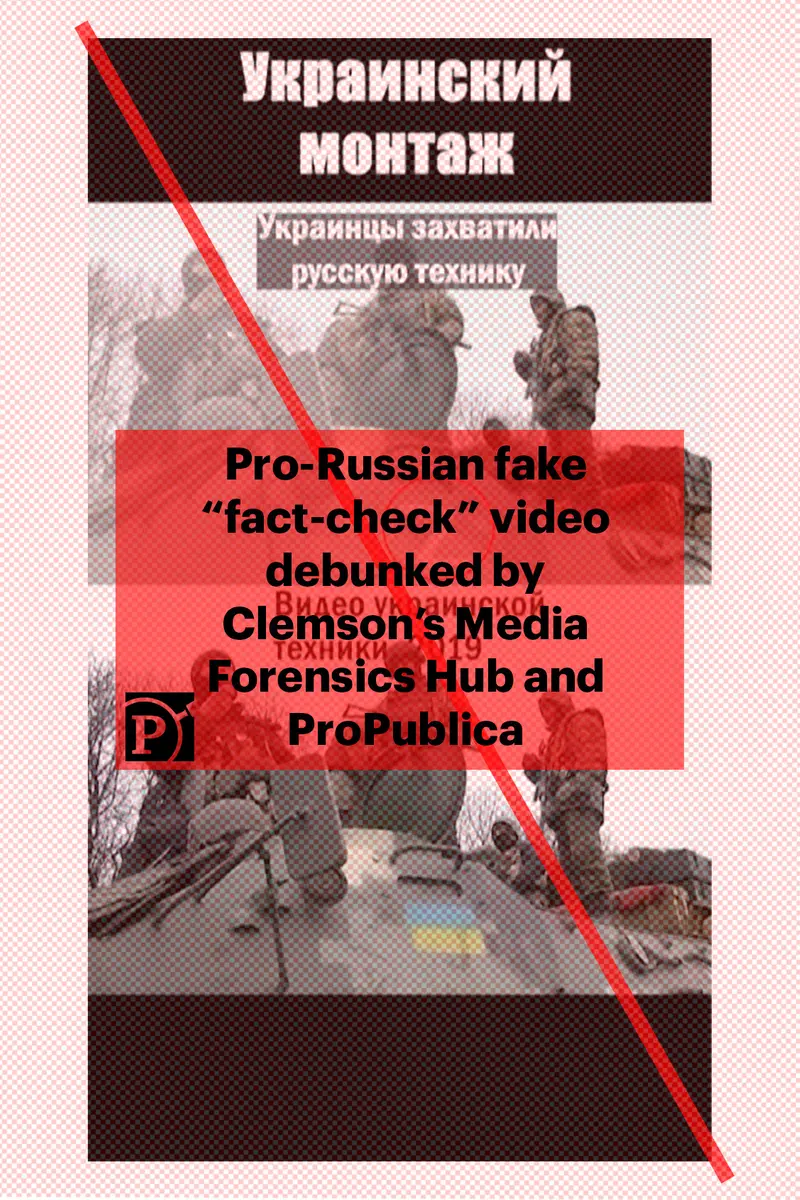

It’s unclear who is creating the videos, or if they come from a single source or many. They have circulated for roughly two weeks, first appearing a few days after Russia invaded. The first video Warren spotted claimed that a Ukrainian flag was removed from old footage of a military vehicle and replaced with a Z, a now-iconic insignia painted on Russian vehicles participating in the invasion. But when he went looking for examples of people sharing the misleading footage with the Z logo, he came up empty.

“I’ve been following [images and videos of the war] pretty carefully in the Telegram feeds, and I had never seen the video they were claiming was a propaganda video, anywhere,” he said. “And so I started digging a little more.”

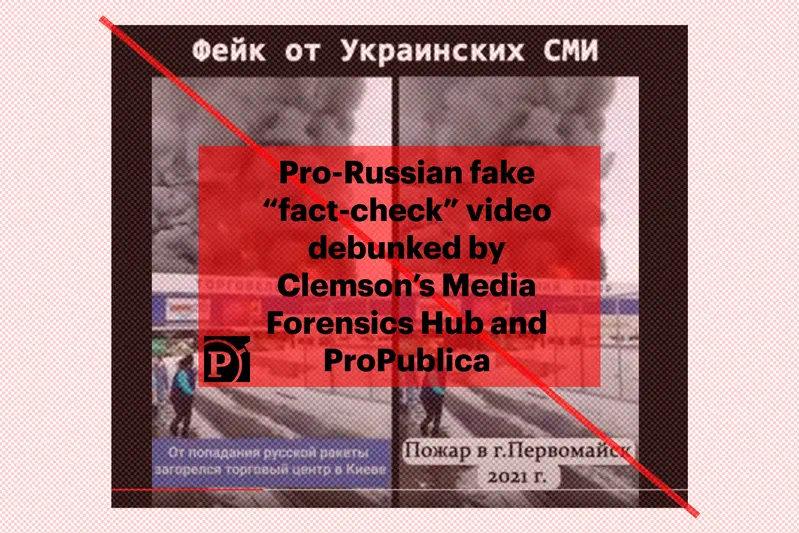

Warren unearthed other fake fact-checking videos. One purported to debunk false footage of explosions in Kyiv, while others claimed to reveal that Ukrainians were circulating old videos of unrelated explosions and mislabeling them as recent. Some of the videos claim to debunk efforts by Ukrainians to falsely label military vehicles as belonging to the Russian military.

“It’s very clear that this is targeted at Russian-speaking audiences. They’re trying to make people think that when you see destroyed Russian military hardware, you should be suspicious of that,” Warren said.

There’s no question that older footage of military vehicles and explosions have circulated with false or misleading claims that connect them to Ukraine. But in the videos identified by Warren, the allegedly Ukrainian-created disinformation does not appear to have circulated prior to Russian-language debunkings.

Searches for examples of the misleading videos came up empty across social media and elsewhere. Tellingly, none of the supposed debunking videos cite a single example of the Ukrainian fakes being shared on social media or elsewhere. Examination of the metadata of two videos found on Telegram appears to provide an explanation for that absence: Whoever created these videos simply duplicated the original footage to create the alleged Ukrainian fake.

A digital video file contains embedded data, called metadata, that indicates when it was created, what editing software was used and the names of clips used to create a final video, among other information. Two Russian-language debunking videos contain metadata that shows they were created using the same video file twice — once to show the original footage, and once to falsely claim it circulated as Ukrainian disinformation. Whoever created the video added different captions or visual elements to fabricate the Ukrainian version.

“If these videos were what they purport to be, they would be a combination of two separate video files, a ‘Ukrainian fake’ and the original footage,” said Darren Linvill, an associate professor at Clemson who co-leads the Media Forensics Hub with Warren. “The metadata we located for some videos clearly shows that they were created by duplicating a single video file and then editing it. Whoever crafted the debunking video created the fake and debunked it at the same time.”

The Media Forensics Hub and ProPublica ran tests to confirm that a video created using two copies of the same footage will cause the file name to appear twice in the video’s metadata.

Joan Donovan, the research director of Harvard’s Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, called the videos “low-grade information warfare.” She said they don’t need to spread widely on social media to be effective, since their existence can be cited by major Russian media sources as evidence of Ukraine’s online disinformation campaign.

“It works in conjunction with state TV in the sense that you can put something like this online and then rerun it on TV as if it’s an example of what’s happening online,” she said.

That’s exactly what happened on March 1, when state-controlled Channel One aired a screenshot taken from one of the videos identified by Warren. The image was shown during a morning news program as a warning to “inexperienced viewers” who might be fooled by false images of Ukrainian forces destroying Russian military vehicles, according to a BBC News report.

“Footage continues to be circulated on the internet which cannot be described as anything but fake,” the BBC quoted a Channel One presenter telling the audience.

At least one Russian government account has promoted an apparent fake debunking video. On March 4, the Russian Embassy in Geneva tweeted a video with a voiceover that said “Western and Ukrainian media are creating thousands of fake news on Russia every day.” The first example showed a video where the letter “Z” was supposedly superimposed onto a destroyed military vehicle.

Another video that circulated on Russian nationalist Telegram channels such as @rlz_the_kraken, which has more than 200,000 subscribers, claimed to show that fake explosions were added to footage of buildings in Kyiv. The explosions and smoke were clearly fabricated, and the video claims they were added by Ukraininans.

But as with the other fake debunking videos, reverse image searches didn’t turn up any examples of the supposedly manipulated video being shared online. The metadata associated with the video file indicates that it may have been manipulated to add sound and other effects using Microsoft Game DVR, a piece of software that records clips from video games.

The fake debunking videos have predominantly spread on Russian-language Telegram channels with names like @FAKEcemetary. In recent days they made the leap to other languages and platforms. One video is the subject of a Reddit thread where people debated the veracity of the footage. On Twitter, they are being spread by people who support Russia, and who present the videos as examples of Ukrainian disinformation.

Francesca Totolo, an Italian writer and supporter of the neo-fascist CasaPound party, recently tweeted the video claiming that a Ukrainian flag had been removed from a military vehicle and replaced with a Russian Z.

“Now wars are also fought in the media and on social networks,” she said.