Inside the medical examiner’s office, two pathologists removed a baby’s lungs from his chest, clamped them together and placed them in a container of water. Then they watched.

They were examining the suspicious death of the baby whose body was found in a Maryland home; his mother said he was stillborn.

If the lungs floated, the theory behind the test holds, the baby likely was born alive. If they sank, the baby likely was stillborn.

“A very simple premise,” the assistant medical examiner later testified.

The lungs floated — and the mother was charged with murder.

In investigations across the country, the lung float test has emerged as a barometer of sorts to help determine if a mother suffered the devastating loss of a stillbirth or if she murdered her baby who was born alive. The test has been used in at least 11 cases where women were charged criminally since 2013 and has helped put nine of them behind bars, a ProPublica review of court records and news reports found. Some of those women remain in prison. Some had their charges dropped and were released.

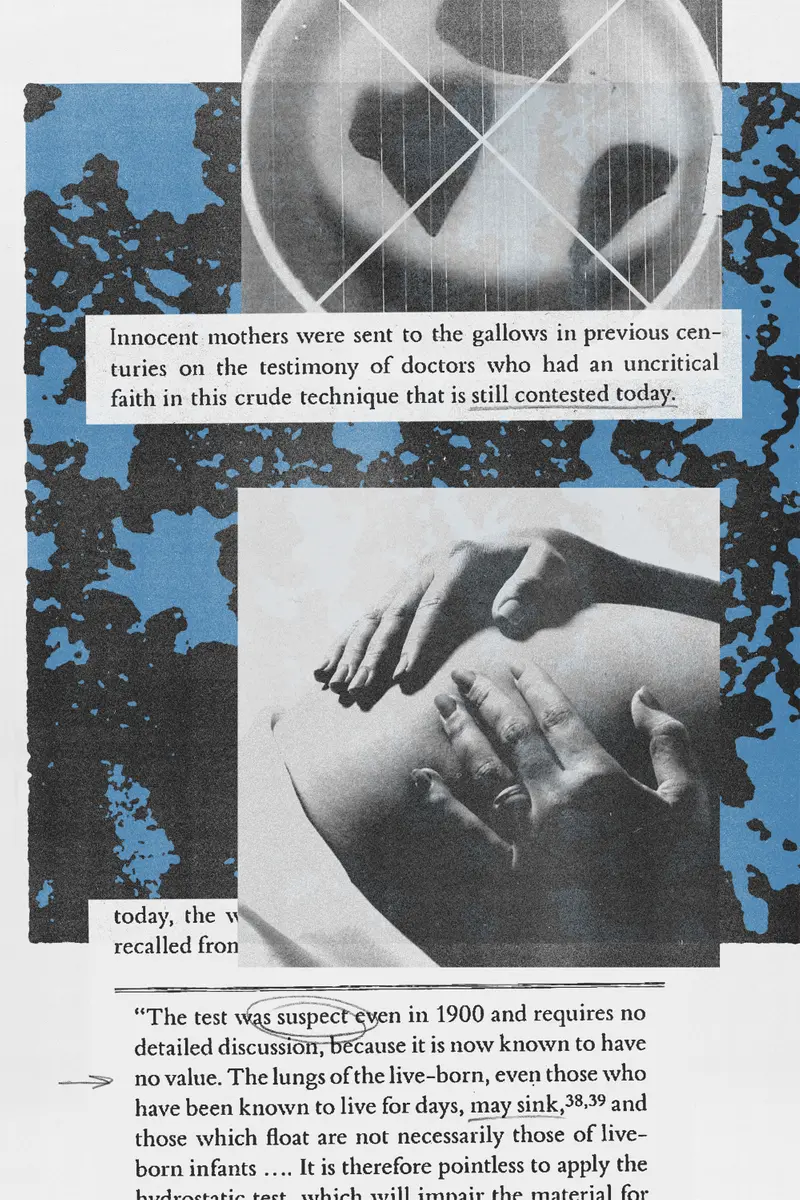

But the test is so deeply flawed that many medical examiners say it cannot be trusted. They put it in the same company as the discredited analysis of bite marks and bloodstain patterns, 911 calls and hair comparisons, all of which lack solid scientific foundations and have contributed to wrongful convictions.

It is pseudoscience masquerading as sound forensics, they say. Some even liken the test to witch trials, where courts decided if a woman was a witch based on whether she floated or sank.

“Basing something so enormous on a test that should not be used, that has been completely discredited, is absolutely wrong,” said Dr. Ranit Mishori, the senior medical adviser for the nonprofit Physicians for Human Rights, which has been studying the test, and a professor of family medicine at Georgetown University School of Medicine. “You can send a person who is innocent to prison for many years.”

Medical examiners who rely on the lung float test typically do so in cases where someone gives birth outside of a hospital, often at home and far from the watchful eyes of medical professionals. Absent those witnesses, doubt can overshadow the insistence that the baby was stillborn.

Since the Supreme Court struck down the constitutional right to abortion, legal experts and reproductive justice advocates have voiced fears that an increased reliance on the lung float test will lead to more prosecutions in a landscape where any pregnancy that doesn’t end with a living, breathing baby can be viewed with suspicion. In several cases, the fact that a woman had considered abortion was used against her. Black, brown and poor women, research shows, already disproportionately face pregnancy-related prosecutions. Black women also are more than two times as likely to have a stillbirth as white women.

Even medical examiners who perform the test as part of an autopsy acknowledge its shortcomings. They concede that there are several ways to perform it, undermining the standardization that many forensic disciplines demand. Yet judges have allowed prosecutors to use it as evidence in court.

“Basing something so enormous on a test that should not be used, that has been completely discredited, is absolutely wrong.”

ProPublica contacted the nation’s largest medical examiners’ offices to ask if they use the lung float test and discovered a patchwork of practices. Many offices said they just don’t trust it. The County of Los Angeles Department of Medical Examiner called its results “inaccurate.” The Harris County Institute of Forensic Sciences in Houston said it found the test to be “very unreliable” and “not supported by empirical evidence.”

In Cook County, home to Chicago, pathologists use it, but give more weight to “more reliable methods” including X-rays, microscopic examinations and autopsy findings to determine whether a birth was live or still. Others, like the Virginia Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, said the test may be useful only if a baby was not born into a toilet, CPR was not performed and decomposition was not present. None of the 12 largest offices by jurisdiction expressed full-throated support for the test.

And while the national organization that represents medical examiners said that it doesn’t have an official stance on the lung float test, it said it “strongly advocates using scientifically validated and evidence-based practices in forensic pathology.” The National Association of Medical Examiners called the lung float test “a single, dated test” that has not been subjected to the organization’s rigorous evaluation process.

Dr. Gregory Davis, a forensic pathologist at the University of Kentucky College of Medicine and a consultant to the office of the medical examiner in Kentucky, called the test “an outrageous breach of science.” He said he has personally observed the lungs of stillborn babies float and those of live-born babies sink.

The fundamental problem with the test, he said, is that there are many ways that air can enter the lungs of a stillborn child.

“There’s no way,” Davis said, “you can determine live birth versus stillbirth with this test.”

Moira Akers, the Maryland woman whose baby died, didn’t intend to get pregnant. She and her husband, Ian, already had two young children and the couple worried they wouldn’t be able to handle another child.

They struggled financially — she was a stay-at-home mom and he worked only a few days a week as a first mate on a dinner cruise. Her previous pregnancies — both ending in cesarean sections — were difficult, and challenges with her youngest child demanded much of her attention.

Due to Akers’ age, 37, and weight, her pregnancy was considered high risk. The couple decided to terminate, but they didn’t tell her family, who are Catholic and who she worried may not have approved. When Akers was a little girl, her mother said, she dreamed of being a mother, and as an adult she doted on her children.

After her appointment with a gynecologist around 15 weeks into her pregnancy, court records show that Akers thought that it was too late for her to have an abortion in Maryland. She decided she would carry the baby to term without letting anyone know she was still pregnant and give it up at a firehouse.

“I wanted the baby to have a good life,” Akers later told police. “I just knew we weren’t going to be able to provide that.”

She didn’t gain much weight and she told her husband early on that the pregnancy had been terminated. She also didn’t divulge the fact that she was pregnant to other family members, who were going through their own hardships, court records and interviews show. Her sister was being treated for cancer and feared she’d never be able to have children of her own. Her brother was recovering from an accident that had left him temporarily using a wheelchair. And the family had recently buried her grandmother and aunt.

Akers declined comment through her attorney. But the description of the case is based on police and court records, including a trial transcript, as well as interviews with her family and her lawyer.

On Nov. 1, 2018, in the family’s three-bedroom duplex in suburban Baltimore, Akers had been having contractions when she felt a strong urge to use the bathroom. She delivered her son into the toilet. She said he was not breathing. She grabbed her older son’s Star Wars towel to wrap the baby in, then carried him into the bedroom to get scissors and cut the umbilical cord.

“I didn’t hear anything,” Akers later told a detective. The baby, she said, didn’t move.

She didn’t know what to do next. Akers scanned the room and spotted a large Ziploc bag meant to store her daughter’s clothes. She placed her baby in the blue bag, and she put the bag in the closet.

Akers was bleeding heavily from the delivery. Blood soaked the carpet and smeared the bathroom floor. It stained the bathtub, closet door and hallway.

Her husband came upstairs. Alarmed by all the blood, he called the paramedics. When they arrived, they asked Akers questions as she sat on the couch with her husband and two children. She denied being pregnant.

It wasn’t until later, after Akers arrived at the hospital, that she told a nurse that she had “delivered a stillborn child” at home, police records show.

The doctors, who came in next, saw a protruding umbilical cord still attached and asked if the baby was alive. Akers said she had delivered a stillborn baby and told them about the bag and the closet.

Police launched an investigation. Akers described being in denial about the pregnancy and sad about the baby’s death.

The two Maryland doctors conducted an autopsy. The baby, they wrote in their report, appeared to be “well-developed” and “well-nourished” and had been delivered after about 41-42 weeks of pregnancy. He had blue eyes and straight brown hair.

Neither the external exam of the baby nor his bloodwork nor an X-ray revealed signs of foul play. But the narrative from police described a woman who hid her pregnancy from her family and paramedics, considered an abortion and placed the baby’s body in a closet. A microscopic view of the lungs, which were soft and pink in some areas, also appeared to show that some parts had air in them and others did not.

They also had the results of the lung float test.

“A flotation test and microscopic examination of the lungs was consistent with a live birth,” the autopsy read. The baby, the medical examiners concluded, died of asphyxia and exposure from being left in the closet.

Prosecutors charged Akers with child abuse and murder.

The lung float test’s simplicity — essentially unchanged over centuries — is both a feature and a flaw.

Some medical examiners take out one lung at a time. Some cut the lungs up and test pieces, and may even go so far as to squeeze them. Others clamp them together or put the heart and lungs in a jar. Some drop in the liver as a control. Others submerge the lungs in liquid formaldehyde instead of water.

As the assistant medical examiner in Akers’ case testified, “there’s a million ways” to conduct the test.

In theory, the test is meant to determine whether air has reached the microscopic air sacs inside the lungs. If it has, the sacs open and spread out. If it hasn’t, the sacs remain collapsed.

“It is not always possible to reach a definitive conclusion, but that may be preferable to [a case] that is based on a problematic test.”

But the problem with using aeration as a proxy for proof of life, many medical experts argue, is that babies don’t have to take a breath for air to enter their lungs. Air can be introduced when the baby’s chest is compressed as it squeezes through the birth canal. If there is an attempt to resuscitate a stillborn baby, that pressure can inflate the lungs. And if a body has started to decompose, gases from that process can cause the lungs to float in water. Even the ordinary handling of a stillborn baby can allow air to enter the lungs.

Doctors have long struggled with the best way to determine whether a baby was born alive in unattended births. Many experts agree that it’s nearly impossible without incontrovertible evidence such as milk in the baby’s stomach or signs of the umbilical cord stump beginning to heal where it was cut.

The uncertainty can be difficult for juries to accept, especially when prosecutors present what appears to be a scientific test that proves a baby was born alive and, as a result, was murdered.

“It is not always possible to reach a definitive conclusion, but that may be preferable to one that is based on a problematic test,” said Capt. Kyle Kennedy of the Oregon State Police department, of which the Oregon State Medical Examiner is a part.

The Oregon State Medical Examiner, he said, does not use the lung float test.

The test can produce correct results, said Dr. Christopher Milroy, a forensic pathologist with the Eastern Ontario Regional Forensic Pathology Unit and a professor at the University of Ottawa in Canada. But given that it also produces inaccurate results, he said it should not be used in criminal cases.

“It’s not like some of the things we do,” he said, “where we are going, ‘Well, did they die of diabetes or did they die of something else natural?’”

Milroy has studied the test and its history and has found references to its use in the 17th century, when witch trials were still occurring. But by the late 1700s, its reliability was questioned by doctors and lawyers. More than 200 years later, in 2016, the authors of a forensic medicine textbook wrote that there were too many recorded instances of stillborn lungs floating and live-born lungs sinking for the test to be used in a criminal trial.

No agency currently tracks how often the lung float test is used in criminal cases. But the 11 cases ProPublica identified are likely an undercount because some cases weren’t covered in news reports, and plea deals and acquittals often create less of a public record.

Still, the test has been cited in medical textbooks and is often included in forensic pathology training. Its defenders say that there aren’t any better alternatives, and they may be criticized for not doing their job if they don’t use it. Some also say they don’t rely solely on the test; they acknowledge its weaknesses but say it complements other exams. In addition, some people do, in fact, kill their babies.

Prosecutors have often turned to a 2013 academic study from Germany to support admitting the lung float test as evidence. “The study proves that for contemporary medicine, the lung floating test is still a reliable indicator of a newborn’s breathing,” the authors wrote.

But some experts have questioned that study, saying its results have not been reproduced, its 98% accuracy rate is misleading and it didn’t actually answer whether a baby was born alive because the births in the study had been attended by medical professionals, so there was never any real question about what happened.

The hospital affiliated with the study’s authors declined to comment.

The dearth of research around the test raises critical questions about whether it should be allowed as evidence, said Marvin Schechter, a New York criminal defense lawyer who served on the committee that wrote a groundbreaking National Academy of Sciences report in 2009 on strengthening forensic science in the United States. Schechter said the lung float test wasn’t included because the commission reviewed only the most frequently cited forensic tests.

His concerns with the test mirror many of the ones flagged in the report. For example, he said, the lack of standardization is evident in the fact that some medical examiners squeeze the lungs as part of the test.

“What is that? Your squeeze is different than my squeeze,” he said. “That’s not science.”

Schechter called for a national conference to evaluate the test and its admissibility in court.

“If you apply the rules and regulations that follow science to the lung float test, how does it pass muster?” Schechter said. “The research doesn’t exist, and if the research doesn’t exist, then you shouldn’t be doing it.”

Every so often, after the lung float test has been used to help put a woman behind bars, the questions around it set her free.

In 2006, Bridget Lee had hid her pregnancy after having an affair. She didn’t want anyone in the small Alabama community where she played piano at her church to know.

When she went into labor at home, she said her son was stillborn. She placed his body in a plastic container and put it in her SUV, where it sat for days.

The medical examiner used the lung float test and concluded that Lee’s son had been born alive. Lee was charged with murder, which in Alabama carried the possibility of the death penalty.

Lee’s lawyer called on Davis to review the autopsy report, which was the first time he saw the lung float test being used to support criminal charges against a mother. He concluded that the autopsy was filled with errors. It missed an infection in the umbilical cord and erroneously described decomposition as signs of injury.

Davis’ review led to the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences to examine the case, and the agency ruled that not only had the medical examiner botched the autopsy, but the baby was stillborn. Neither the medical examiner nor the prosecutors responded to requests for comment.

Lee spent nine months in jail before prosecutors dropped the charges against her.

She later told reporters that she knows it’s hard for people to understand how she could put her baby’s body in a container and leave it in her car. But, she said, the best way to describe it was like having “an out-of-body experience.”

While individual reactions are hard to comprehend, mental health specialists say the shock and pain of delivering a stillborn baby at home can be so traumatic that people may detach or disassociate from reality, said Dr. Miriam Schultz, an associate clinical professor of psychiatry who specializes in reproductive psychiatry at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health.

“Sometimes a survival instinct will kick in to try to normalize what’s an absolutely incomprehensibly shocking and devastating reality,” Schultz said. “One could imagine possibly trying to make evidence of what just happened less visible and wanting to completely compartmentalize this traumatic event that just has occurred.”

Late one April night in 2017, Latice Fisher said she felt the urge to defecate. About three hours later, she delivered her son into the toilet at her home.

The medical examiner in Fisher’s case performed the lung float test, which revealed that parts of the lungs floated and parts didn’t. He ruled that the baby was born alive and died from asphyxiation. Police also found that Fisher had searched for abortion pills on her phone.

Yveka Pierre, senior litigation counsel with the reproductive justice nonprofit If/When/How, said the people who are prosecuted for their pregnancy outcomes are typically from marginalized communities. They’re Black, like Fisher; or they’re brown, like Purvi Patel, an Indiana woman who was sent to prison for feticide after self-inducing an abortion, a charge that was later vacated; or they face financial hurdles, like Akers.

“Some losses are tragedies, depending on your identity, and some losses are crimes, depending on your identity.” Pierre said. “That is not how we say the law should work.”

Pierre, who also worked on Akers’ case, said Fisher and her husband did what prosecutors say to do by calling 911, but Fisher was still arrested. Once the medical examiner’s investigation starts, she said, the office typically works in tandem with the police.

A grand jury indicted Fisher on second-degree murder charges in January 2018. But a few months later, a local group raised money to get her released on bond. The group also contacted a national nonprofit, now known as Pregnancy Justice, which helped connect Fisher with longtime criminal defense attorney Dan Arshack. He began researching the lung float test and came to an unmistakable conclusion.

“It should be permitted to the same extent that dunking a woman in water is permitted to determine if she’s a witch,” he said in an interview.

“Some losses are tragedies, depending on your identity, and some losses are crimes, depending on your identity. That is not how we say the law should work.”

Arshack asked Davis to review the autopsy, which he found troubling. Arshack also asked Aziza Ahmed, then a professor at Northeastern University School of Law, to focus specifically on the forensics of the lung float test.

By not requiring rigorous testing or proof of its accuracy, Ahmed wrote, the “courts themselves have played a key role in sustaining the inaccurate belief” that the test could reliably determine whether a child was born alive.

Arshack wrote letters to District Attorney Scott Colom explaining Davis and Ahmed’s findings, saying there was no “reasonable legal or scientific basis” to conclude that a crime occurred. He also explained that it wasn’t “good public policy to prosecute women for bad pregnancy outcomes, especially Black women in Mississippi,” who suffer higher rates of maternal mortality and stillbirth.

In May 2019, Colom announced that he had learned of concerns surrounding the reliability of the lung float test. Once the question of whether the child was born alive was scientifically in dispute, he said, he dismissed the charges against Fisher and sent the case to another grand jury armed with the details about the test.

“When you’re talking about a murder charge for a mother,” Colom said in an interview, “I felt that was crucial information because I certainly didn’t want to be prosecuting somebody for a stillborn death that could not be her fault.”

This time, the grand jury chose not to indict Fisher.

As Akers’ case made its way through court, Davis was asked to review the autopsy. He noted that Akers had classic risk factors for stillbirth: hypertension during pregnancy, obesity, advanced maternal age and previous pregnancies. She also was past her due date and reported not feeling the baby kick in the days leading up to the birth.

Davis agreed with the medical examiner, Dr. Nikki Mourtzinos, and the associate pathologist who conducted parts of the autopsy, that there were infections in the pancreas, placenta — the vital organ that provides the fetus with nutrients and oxygen — and the umbilical cord, which serves as the baby’s lifeline in the womb.

But what he found “perplexing,” he wrote, is that they did “not seem to take these critical findings into account regarding such findings being associated with stillbirth.” When it was his time to take the witness stand at trial, he said the infections in the placenta, umbilical cord and membranes were “a smoking gun association” with stillbirth.

An OB-GYN also testified that he believed Akers suffered from a placental abruption — a complication where the placenta separates from the wall of the uterus — which also can lead to a stillbirth and cause heavy bleeding.

Prosecutors said the case hinged on whether the baby was born alive. Among the evidence they pointed to were the results of the lung float test, the pinkish appearance of the lungs and lack of decomposition, malformation of the baby’s head or slippage of the skin.

“These lungs floated,” the prosecutor said during closing. “They floated because this child had breathed and was alive after he was delivered at home that day.”

The prosecution homed in on the fact that Akers had wanted an abortion, which was underscored by her cellphone search history. They said she never intended to have her baby live and breathe. When she didn’t get an abortion, they said, she chose to give birth at home and kill her son. They pointed out that she hadn’t received prenatal care and that she didn’t attempt to resuscitate the baby.

Akers told police she thought it was too late.

During closing arguments, prosecutors displayed an oversized photo of the baby on the screen and repeated that Akers put his body in a bag, using the word “bag” 26 times.

In April 2022, the jury found Akers guilty of second-degree murder and first-degree child abuse.

In response to questions from ProPublica, the state’s attorney declined to comment. Mourtzinos, the assistant medical examiner who testified in Akers’ case, did not respond to requests for comment. She’s no longer with the Maryland medical examiner’s office. The agency’s interim chief medical examiner said the office is accredited by the National Association of Medical Examiners and follows the organization’s autopsy performance standards. Any and all ancillary tests, she said, “are done on a case by case basis, at the discretion of the attending medical examiner” and interpreted in the context of the entire case.

When the verdict was read, Akers collapsed in her chair, dropped her head to the table and sobbed. Her family, who was seated behind her, filled the courtroom with their own cries.

Last summer, as much of the country awaited the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, which eliminated a constitutional right to abortion, the New York-based nonprofit Pregnancy Justice released a guide for medical, legal and child welfare professionals on confronting pregnancy criminalization.

The organization advised defense attorneys and medical examiners to challenge the lung float test. In many cases, the authors wrote, criminal charges are based on “the erroneous assumption that a woman engaged in acts or omissions that harmed the fetus.”

The backdrop to the lung float test is the deeper issue of criminalizing pregnancy loss. That was already on the rise before the Dobbs decision, with data from Pregnancy Justice showing that nearly 1,400 pregnant women were arrested, prosecuted or sentenced between 2006 and the 2022 Dobbs decision, more than three times the total for the previous 33 years. Many of the charges were connected to drug use while pregnant.

Society often wants to hold someone responsible, said Dana Sussman, deputy executive director of Pregnancy Justice. Mothers are usually the easiest to blame.

One of the first things Pregnancy Justice lawyers now ask in a pregnancy loss case is whether the prosecutor is attempting to use the lung float test.

“It’s almost like an intake question,” Sussman said. “We will fight every attempt that we learn of to use that test because that is a life sentence based on unreliable information and unreliable science.”

The lack of understanding, research and education around stillbirth also contributes to the urge to assign blame. Every year in the U.S., more than 20,000 pregnancies end in stillbirth, defined as the death of an expected child at 20 weeks or more. But the public is often shocked to hear that number or learn that only a fraction of stillbirths are attributed to congenital abnormalities. Some babies died just minutes before they were born and were placed in their parents’ arms while they were warm to the touch and their cheeks were still rosy.

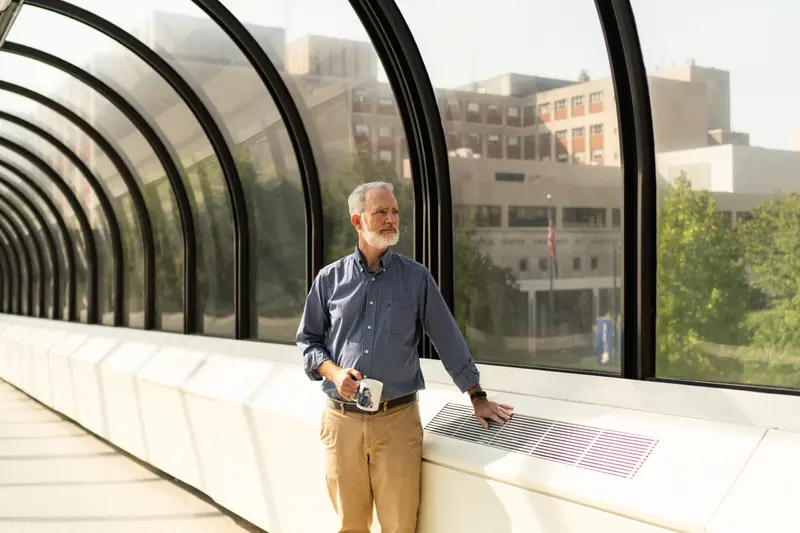

Davis, an affable man with a snow-white beard, has started to spread the word about the lung float test. At a post-Dobbs legal seminar in Tennessee over the summer, he told a room of lawyers about the test, one that many of them had not heard of but may soon encounter.

A lawyer sitting in the back told the crowd that the lung float test seemed to have the same validity as bite mark analysis, which for decades was accepted as evidence and now is considered junk science.

“What do you do when they say this test has been accepted in the past?” she asked.

Davis pointed her to a letter where he gathered signatures from more than two dozen forensic pathologists and medical examiners from around the world who declared that the lung float test is not a scientifically reliable test or indicator of live birth and “is not generally accepted within the forensic pathology community.”

He had submitted the letter in Akers’ case.

In July of last year, three months after the Akers verdict, prosecutors asked the judge to sentence her to 40 years. They said it was the “the most heinous of crimes that can be committed” and it was carried out by a woman who hid her pregnancy and took her baby’s life in a “detached and calculated manner.”

Akers’ family came to her defense. Her husband said that in their nearly 20 years together, Akers’ “devotion to her family defies description.” One of his greatest joys in life, he said, was seeing the way their kids light up anytime she enters a room.

Her lawyer, Debra Saltz, said Akers made “lapses in judgment” by not telling anyone she was pregnant, having the baby alone and then putting his body in the closet. But, she said, “There is in this life no way anybody will get me to believe that Moira Akers killed her baby. I believe Moira, and I believe the science, that this baby was stillborn.”

Before the judge imposed his sentence, Akers addressed him.

“My children are my entire world,” she said, “and I fell in love with my son as soon as I saw him.”

The judge, who acknowledged what an “extraordinarily difficult case” it was, said the charges against Akers were “particularly egregious because they were perpetrated against an innocent, helpless, newborn child.”

He sentenced her to 30 years in prison.

Akers’ appeal, now pending, focuses on the shortcomings of the lung float test.

As she waits for a ruling, she stays connected to her family from prison. Her mom, Mary Linehan, said most of their conversations revolve around the ordinary details of her children’s lives, their first day of school and their favorite new toys.

Akers’ mom, who retired from her job as an accountant at a Catholic church and school, helps watch her grandchildren. When they ask about their mom, she said, their dad tells them that she “got blamed for something she didn’t do, and we’re fighting to get her out.”

Mariam Elba contributed research.