This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with WVUE-TV. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Update, Dec. 15, 2023: This story has been updated to reflect the fact that after this story was published, another town — Tullos, Louisiana — said that it had appointed a magistrate following WVUE and ProPublica’s inquiries.

Amid questions about how he ran his court, the mayor of the tiny village of Fenton, Louisiana, recently decided he would no longer serve as the town judge.

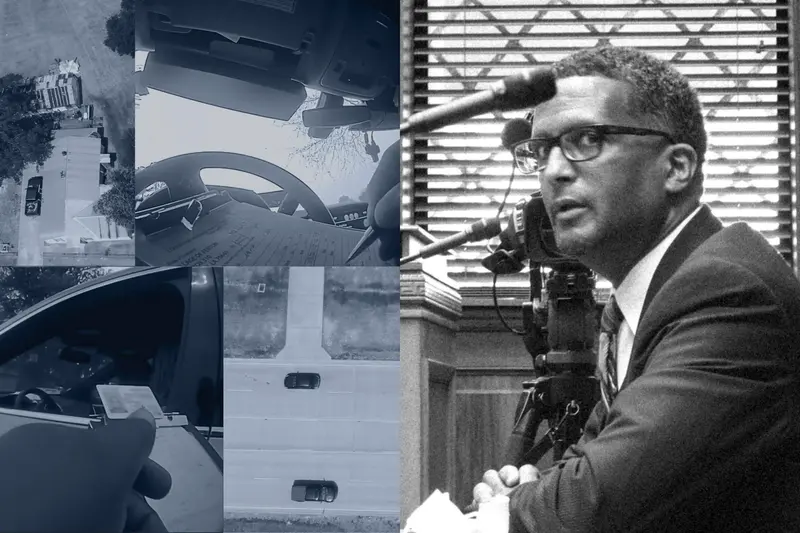

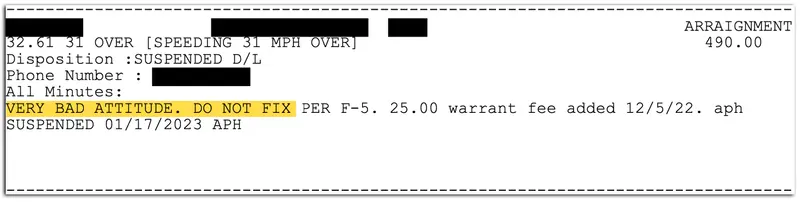

He had been recorded saying police officers must write more tickets and now found himself defending his impartiality. Some court records included notations by officers and village employees saying not to “fix” certain tickets; other notations said tickets were dropped after someone, often a law enforcement officer, had intervened.

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that having a mayor serve as judge is unfair to defendants if a town brings in a substantial part of its revenue through the court and if the mayor is responsible for the town’s finances. The court in Fenton brought in 92.5% of the town’s revenue in one recent year, but the mayor still sat on the bench.

After WVUE-TV and ProPublica reported on what was going on, the mayor last month appointed an attorney to preside over the court instead.

Mayor’s courts, where the authority to enforce local ordinances by default rests with the mayor, exist in small towns throughout Louisiana, which commission annual audits that show how much money each town takes in. The state auditor’s office holds those reports, but it doesn’t track which towns take in enough money from their court to create a potential conflict of interest.

WVUE and ProPublica decided that we would. Looking at recent audits for all municipalities in Louisiana that file them, we could see which towns took in the greatest share of their revenue through fines and related costs. Starting with the towns other than Fenton that collected the highest percentage, we began calling around to confirm that all that money came through their mayor’s court.

Of the 15 towns we reached in the last several weeks, 13 had mayors on the bench even though their courts brought in anywhere from 14% to 82% of their total governmental revenue in the fiscal year ending in 2022. The Louisiana Judicial College, the educational arm of the state Supreme Court, recommends that mayors appoint someone else to serve as judge if their town takes in at least 10% of its overall revenue from court.

Told of our findings so far, a state lawmaker is calling for reform of a court system that exists only in Louisiana and Ohio.

“If 48 states can live without mayor’s court, why can’t we?” said state Rep. Edmond Jordan, a Democrat from Baton Rouge. “You got the town attorney acting as the prosecutor. So everybody is in on the game, except the person being charged with the offense.”

You got the town attorney acting as the prosecutor. So everybody is in on the game, except the person being charged with the offense.”

Jordan said he wants to create a task force to study mayor’s courts. Unlike other courts in Louisiana, they don’t have to follow rules of procedure designed to ensure that they’re run fairly and properly. And unlike municipal judges, who handle the same types of offenses, mayors do not need a law degree to adjudicate cases. Until this year, they weren’t required to undergo any training.

Last year, Jordan filed a bill to abolish mayor’s courts, but it was opposed by the Louisiana Municipal Association, which advocates for the interests of villages, cities and towns. Jordan then tried to require towns with mayor’s courts to appoint attorneys to preside over their courts, but lawmakers resoundingly voted the bill down.

Seven of the mayors in those 13 towns said they’re not convinced they’re doing anything wrong, including four who said they believe they treat defendants fairly despite their reliance on the court for a large portion of the town’s budget. Two of those who defended their practices also said they can’t afford to pay someone else to preside. One said if he finds out that he needs to appoint someone, he will.

However, two towns — Albany, east of Baton Rouge, and Tullos, in north Louisiana — responded by appointing magistrates.

Most of the 13 towns identified by the news organizations are home to just a few hundred people. They include Turkey Creek, in south-central Louisiana, where the police department is funded entirely by citations.

The village of Dodson, located in north-central Louisiana, collected half a million dollars — 73% of its total revenue — from its mayor’s court in the year ending in June 2022.

Henderson, a town of about 1,600 just east of Lafayette on Interstate 10, had revenues of about $3.5 million in the year ending in June 2022, according to an audit. About $2 million of that came through its court.

Of the 301 municipalities and two combined city-parish governments required to file audits, we found 91 with mayor’s courts that collected 10% or more of the municipality’s revenue through fines and forfeitures in a single year. (Although the state provides no official definition of “fines and forfeitures,” it generally refers to penalties for breaking the law and associated fees.) We called those courts to see who presided — in some courts, the mayor has appointed a magistrate instead — and to confirm how much of that money came through court.

Competing Advice for Small Town Mayors

Starting this year, anyone who presides over a mayor’s court in Louisiana must complete three hours of video training provided by the state Judicial College, in which the trainer says he “would highly recommend” appointing a magistrate if a town’s court generates at least 10% of its revenue.

Mayors in all 13 towns we identified have taken that training. Two of them pointed out that the guidance about appointing someone else was phrased as a recommendation. Two others said they had followed different advice, including one who said he talked to the Louisiana Municipal Association. About 250 of the association’s 300 or so members have mayor’s courts, and the association publishes a lengthy guide on how to run them.

The Judicial College’s advice is based on a federal court ruling in Ohio, which held that 10% would be considered a “substantial” share of town revenue under the 1972 Supreme Court opinion that addressed the fairness of mayor’s courts. The Ohio town in the Supreme Court case generated between 37% and 51% of its annual revenue through its court.

Bobby King, the prosecutor for a mayor’s court outside Baton Rouge, led much of the Judicial College training. Mayors whose courts take in a substantial amount of money “can be in a bind” if they sit on the bench, he said in the training. If a mayor presides, he said, “you can be held that you’re violating people’s constitutional rights to due process.”

After watching the videos, the mayor of Brusly, whose court accounts for 17% of its revenue, said he asked the Municipal Association if he needed to appoint a magistrate. Mayor Scot Rhodes said he was told by someone in the association’s legal department that the threshold doesn’t apply to the many cases in which defendants simply pay their fines. Instead, he said he was told, it applies only to revenue from the few cases in which defendants appear in court before him to fight their tickets or ask for a break. “I’ve been advised that we’re doing everything on the up-and-up,” he said.

Henderson Mayor Sherbin Collette said he came to the same conclusion after a training session at the Municipal Association’s convention in 2022. “If we find out that it is better that we have a magistrate,” Collette said, “we are going to see that it happens.”

Karen White, executive counsel for the association, told WVUE and ProPublica in an email that the association “does not provide legal guidance, opinions, or advice to municipal members”; that’s up to each municipality’s attorney. When the association participates in events with other entities such as the Judicial College, the state Supreme Court or the legislative auditor, “there are times in which a remark is attributed, innocently but erroneously, to a particular entity.”

White wrote that it is problematic to “adopt a singular guideline for all municipal governments in the state” because there are wide variations in how towns are chartered and operated. “There has been no rule from the U.S. Supreme Court to support any definite threshold as triggering the mandatory appointment of a magistrate.”

The association’s 210-page guide to mayor’s courts says that “it seems prudent that, when possible,” a magistrate be appointed to oversee the court. If a town can’t afford it, the guide says, the mayor should try as much as possible to “separate their duties” as presiding officer of the court from their duties as the town’s chief executive.

The Municipal Association’s guide also offers an alternative: a “hybrid” arrangement in which the mayor handles guilty pleas but an appointed magistrate oversees proceedings in which someone pleads not guilty, as well as any trials or hearings that may be required.

In northeast Louisiana, the mayor for the village of Baskin, which took in 70% of its revenue from mayor’s court in one year, told WVUE and ProPublica that he is considering a hybrid approach when we asked why he presides over court. “I get everyone’s frustration,” Mayor Layton Curtis said. “We really need to be respectful of everybody.”

Mayor’s courts play an integral role in ensuring public health and safety, as their jurisdiction encompasses the enforcement of all municipal ordinances.”

Woodworth, near the central Louisiana city of Alexandria, is one of two towns among the 13 that now use that approach. Mayor David Butler said he does this because he doesn’t “want to show any partiality,” although he believes he treats defendants fairly. He said he’s been on the bench long enough that he can read people — “whether they are honest or not honest.”

However, King said he doesn’t believe the hybrid approach addresses a potential conflict of interest for any town where the court takes in at least 10% of revenue. In his training, he tells people that what matters is total collections.

White wrote that questions about conflicts of interest are not unique to mayor’s courts because all types of courts in Louisiana receive some funding from the fines and fees they impose.

“Mayor’s courts play an integral role in ensuring public health and safety, as their jurisdiction encompasses the enforcement of all municipal ordinances,” she wrote. “Neither mayors nor council members have any control over how many persons violate traffic and other ordinances, nor how often.”

“As Long as They Don’t Have a Bad Attitude, I Try to Help Them”

Proponents of mayor’s courts say they’re an efficient, informal way to administer justice in small towns. Several mayors said they run their courts simply and fairly, usually without holding trials.

Dodson Mayor Richie Broomfield, who also does maintenance for the town, wears jeans and work boots to court. “I don’t want to intimidate anybody. I don’t want anybody to think bad of me,” he said. “They don’t even stand up, we just sit there and talk.”

But as court records in Fenton suggest, not all drivers are treated the same. There, some records included notations from officers and village employees not to “fix” tickets or “help” drivers who had a “bad attitude.” Fenton village attorney Mike Holmes said cases are adjudicated based on provable violations of law, not those notations.

Broomfield also takes into account drivers’ behavior. When people come to court, he said, they’re usually polite. But that doesn’t mean they were nice when they were stopped, so he reads officers’ notations about drivers’ behavior. “I think I’m very fair,” Broomfield said, noting that speeding cases are often clear-cut. “As long as they don’t have a bad attitude, I try to help them.”

Albany had court revenue of $200,000 in the year ending in June 2022 — about 14% of its overall revenue.

John Boudreaux, a former reserve police officer who lives near Albany, was ticketed there in August for speeding and having an expired license plate. What he found when he went to court to fight the ticket was “very odd,” he said: The mayor was presiding.

“I didn’t even know that existed until that night,” he said. “Either you need to be a mayor or you need to be a magistrate; you can’t be both.”

He said the prosecutor told defendants that if they pleaded not guilty, they would end up being found guilty in a trial and they would end up paying more money.

Keith Rowe, the prosecutor at the time, told WVUE and ProPublica he didn’t say that to defendants and told them instead that they’re presumed innocent. But he said he did tell defendants that they “more than likely” would be found guilty if an officer testified against them. “I just try to tell them the real facts,” Rowe said.

Boudreaux is appealing his case to the local district court.

In an email, Mayor Eileen Bates-McCarroll told WVUE and ProPublica that she knows about “the suggestion” that towns appoint a magistrate and she was considering it. Monday night, the town’s board of aldermen took that step. Rowe will no longer prosecute cases; now he will preside over court.

Joel Jacobs of ProPublica reviewed the data analysis.