Legal experts from two universities will convene a group to study a dubious forensic test that has helped send some women to prison for murder though the women insisted they had stillbirths.

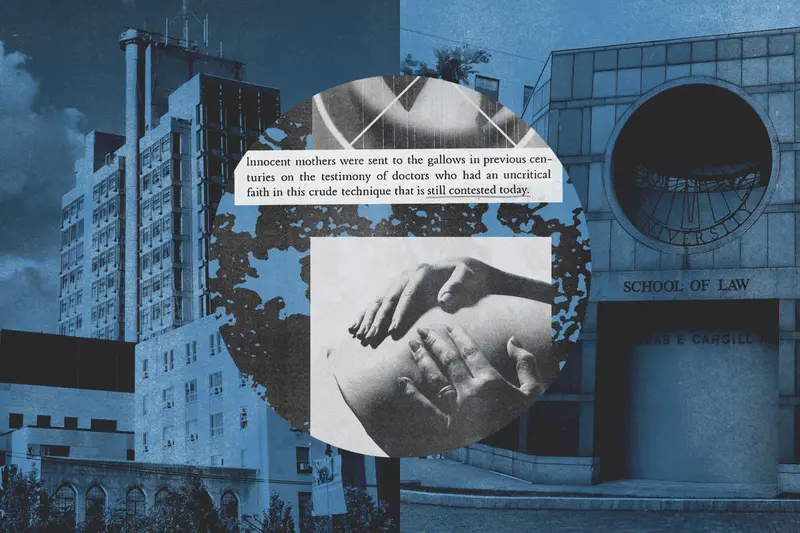

Last month, ProPublica reported on what’s known as the lung float test, which some medical examiners use to help determine whether a child was stillborn or was born alive and took a breath.

In response to the investigation, Aziza Ahmed, a professor at Boston University School of Law, and Daniel Medwed, professor of law and criminal justice at Northeastern University, announced they will lead the Floating Lung Test Research Study Group. The group, which will consist of lawyers and medical professionals, will be sponsored by the Boston University Program on Reproductive Justice and the Center for Public Interest Advocacy and Collaboration at Northeastern University School of Law.

“This is entirely due to the ProPublica report,” Ahmed said last week. “We realized it was time to take action.”

The aim of the group is to study the medical underpinnings of the lung float test, also referred to as the floating lung test, and determine whether it should be used in court. ProPublica’s reporting found that although several medical examiners said the test is unreliable, it had been used in at least 11 cases since 2013 in which women were charged criminally, and it has helped to put nine of those women behind bars. Some later had their charges dropped and were released.

The test, which has been around for centuries and remains essentially unchanged in spite of medical advances, is typically used in cases when births occurred outside of a hospital. Critics have likened the test to witch trials, when women were deemed to be witches based on whether they floated or sank.

When told about the study group, Dr. Joyce deJong, president of the National Association of Medical Examiners, said the organization “supports initiatives that aim to enhance forensic tests’ scientific rigor and reliability.” It doesn’t have an official stance on the test, but deJong said a primary role is to “promote best practices and standards in forensic pathology and death investigation.”

If the study group asks for board-certified forensic pathologists to participate, the organization could share the request with its members, deJong said.

The group leaders plan to spend the next several weeks assembling a team and hope to have their first meeting early next year.

“The process will be robust and comprehensive,” Medwed said. “We will explore and interrogate any argument, pro and con.”

Many medical experts say that air can enter the lungs of a stillborn child even without breathing. Air can enter when the baby’s chest compresses as it squeezes through the birth canal, through CPR or during the ordinary handling of the body. If the body is decomposed, gases may cause the lungs to float.

Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to strike down the constitutional right to abortion, experts fear the test may play a larger role in cases when police and prosecutors raise questions about the circumstances of a birth.

“There’s a concern that more women would be vulnerable to prosecution, especially if they tried to self-induce later in pregnancy,” Ahmed said. “In this environment, the floating lung test is something that prosecutors would rely on.”

Medical and legal experts have pointed to wide variations in how the test is conducted, including the fact that some medical examiners use a whole lung while others use pieces. Experts have said the lack of standardization required by other forensic disciplines, such as DNA testing, has led to the lung float test producing inaccurate results.

Medwed, who also is a founding member of the board of directors of the Innocence Network, a coalition of organizations dedicated to fighting wrongful convictions, said that nearly 25% of wrongful conviction cases since 1989 involved some type of flawed science.

Because the lung float test is conducted by medical examiners, Medwed said, he worries the “mystique of the white coat” leads judges and jurors alike to overvalue the test. Similar concerns have been raised about shaken baby syndrome, which has faced increased scrutiny in recent years. There’s a natural deference to the expert, he said, and specifically the expert best at persuading a jury.

“The downstream consequence,” he said, “could be a wrongful conviction.”

Even supporters of the test acknowledge its drawbacks, conceding there are many ways to perform it and that they shouldn’t rely solely on the test when investigating a death. Despite those shortcomings, judges have allowed prosecutors to use it as evidence in court.

ProPublica wrote about the case of Moira Akers, a Maryland mother who insisted she had a stillbirth but last year was sentenced to 30 years in prison after a jury found her guilty of child abuse and murder. The medical examiner in the case relied on the lung float test. The state’s attorney’s office declined to comment while the case was on appeal.

The Appellate Court of Maryland is set to hear Akers’ appeal in early January.