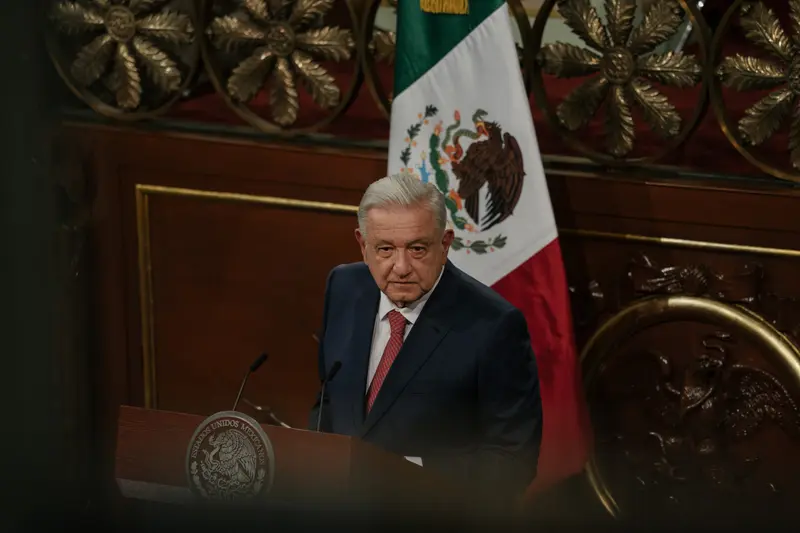

Almost every weekday at 7 a.m., Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador holds a press conference known in Spanish as “la mañanera,” or, loosely translated, the morning show. He takes questions from reporters, but his purpose is to control the news, recounting his achievements and bashing his enemies, real and perceived — especially those in the media.

Since last week, López Obrador has focused much of his ire on an article we published on Jan. 30 about allegations that drug traffickers contributed $2 million to his first, unsuccessful presidential campaign in 2006. He dismissed the story as “completely false” and “slander.”

The president has been aggressive in attacking the story’s reporter, Tim Golden, calling him “a mercenary in the service” of the Drug Enforcement Administration, a tool of the U.S. State Department and “pawn,” among other things. “As far as I’m concerned, they should give him the prize for slander,” he said of Golden, who has twice shared the Pulitzer Prize.

On Wednesday, López Obrador challenged Golden to come to the National Palace in Mexico City to answer questions about the origins of the story, why we wrote it and the identity of his sources in the United States and Mexico.

Although Golden might enjoy the debate, he won’t be appearing on the morning show. He made extensive efforts to include López Obrador’s views before the piece ran. We contacted the president’s chief spokesperson more than a week before publication and provided a detailed summary of the story’s findings along with a series of questions. After numerous requests, the spokesperson promised a reply, but we never received one.

ProPublica has requested an interview with López Obrador about the story and the questions it raises, and we would speak with him as we would any other head of state — not for an episode of the regular mañanera segment he calls “Who’s Who in the Lies?”

I do think it’s useful to engage the president on the legitimate questions he has posed about why we are doing this reporting and how we went about it.

To recap: Our story, which was based on interviews with current and former officials and a review of government documents, disclosed the existence of a previously secret investigation by the DEA into reported donations to López Obrador’s 2006 presidential campaign by traffickers working with the so-called Sinaloa Cartel.

The case began when a Mexican drug lawyer working as an informant for the DEA reported in 2010 that he had participated in the meeting at which the donations were first negotiated, officials said. He reported having given most of the agreed-on funds to an operative in López Obrador’s 2006 campaign, Mauricio Soto Caballero. The informant then enticed Soto to come in on a small-time cocaine deal. DEA agents arrested Soto in McAllen, Texas, and he agreed to work undercover for the Americans to stay out of federal prison.

Ultimately, three other witnesses, including Soto, confirmed the drug lawyer’s account to the DEA, officials said. To gather more evidence for a possible corruption case, the DEA had Soto surreptitiously record two conversations with the man to whom he said he had given most of the traffickers’ money, Nicolás Mollinedo Bastar, one of López Obrador’s closest aides.

Justice Department prosecutors reviewed the tapes and found them incriminating but not decisive, people familiar with the case said. DEA agents wanted to go forward with a more elaborate sting operation inside Mexico, but DOJ officials rejected that plan in late 2011, in part over concerns that even a successful prosecution would be viewed by Mexicans as egregious American meddling in their politics.

The case was closed and, to our knowledge, no further investigation of López Obrador or his inner circle’s possible links to drug traffickers was pursued by U.S. investigators.

(Soto did not respond to our repeated questions about his role in the U.S. investigation, but he denied in recent interviews that he acted as a confidential source or taped his friend and colleague Mollinedo. In an interview, Mollinedo told us he never received donations from drug traffickers, disputed that López Obrador would ever tolerate such corruption and said he knew nothing of any U.S. investigation involving his friend Soto.)

López Obrador was elected president in 2018 after promising a turn away from confrontation with Mexico’s powerful crime groups. He called the policy “Hugs, not bullets” and immediately began to scale back counterdrug cooperation with the United States.

Some critics of our reporting have asked why we pursued an allegation of corruption that dates back to 2006. It’s a fair question. We viewed this as a case study of the conflicting pressures faced by U.S. officials when they learn of possible corruption in Mexico. While some American officials feel that policing government corruption should be a Mexican responsibility, others note that government collusion has been a crucial element (along with a porous 2,000-mile border and a vast illegal drug market in the United States) fueling the drug gangs’ rise as a global criminal force.

The power of those gangs, which lord over large swaths of Mexican territory and extort businesses across the economy, has become a growing national security problem for both countries. In the United States, annual deaths from drug overdoses have surged over 100,000 in recent years. Hugs notwithstanding, criminal violence in Mexico remains at historic levels. After more than 15 years and $3.5 billion dollars in U.S. aid, bilateral efforts to overhaul Mexico’s criminal justice system have faltered badly.

Washington officials’ ambivalence in the face of Mexico’s corruption problem has become even more acute as immigration has taken center stage in American politics: U.S. officials understand that López Obrador’s administration could react to criminal charges against its officials by easing efforts to stop migrants at the border.

While it might disappoint López Obrador, we do not reveal the identities of the present and former government officials who speak with us for these stories. But we can offer some context on the latest article. This was not an orchestrated leak; the Biden administration officials with whom we spoke were uniformly dismayed that it was going to appear. A spat with a Mexican president — much less any threat of conflict on the immigration front — is not a backdrop they’d like to see for a 2024 presidential election.

López Obrador’s attacks from the palace podium have been personal and vituperative. So here are a few facts. Golden has been reporting on Mexico for three decades, first as The New York Times bureau chief in Mexico City and then as an investigative reporter for the Times and ProPublica. He began working on this story months ago, and the details emerged only from dozens of interviews and internal documents.

López Obrador has advanced multiple theories about how this story came to be. This week, he suggested that Golden was somehow in cahoots with the discredited former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, whom he covered in the early 1990s. While Golden did have good sources inside the government in those days, he also produced dozens of deeply reported stories about the explosion of the drug trade under Salinas, the growing shadow of Mexican corruption and the failure of the United States to deal effectively with either problem. That work continued during the tenure of Salinas’s chosen successor, Ernesto Zedillo, whose administration also complained about stories that exposed allegations of high-level corruption.

Some in Mexico have speculated around the fact that similar stories about drug traffickers’ contributions to the 2006 campaign appeared in three foreign outlets simultaneously. Surely, they argue, that is clear circumstantial evidence of a coordinated U.S. campaign to leak information that might undermine the Mexican government.

The truth, as it so often is, is far more mundane. Early in our reporting, we realized that a respected U.S. news organization, InSight Crime, was pursuing the same allegations. Sometimes we collaborate — or compete — in such circumstances. In this case we agreed with Insight Crime that we would each work independently to produce the most thorough and careful stories we could, but coordinate our publication date. We delayed publication and rewrote our stories in order to address a request from the DEA that we not name any confidential government sources.

As sometimes happens, though, a Mexican reporter who writes for the German outlet Deutsche Welle published her own account of the donations and named Soto as a DEA source. With that information public, InSight Crime and ProPublica went ahead and included it in our stories.

Within hours, López Obrador was assailing all three reporters as “vile slanderers.”

The tactic of attacking reporters who reveal uncomfortable truths is as old as democracy itself. But the advent of social media has taken the power of attacks on journalists to new heights. Politicians like López Obrador can now use their platforms to say whatever they want about a reporter and then stand back as armies of friends and bots amplify the message across the internet.

That experience can be difficult for American reporters. But it is a deadly serious business in Mexico, where journalists who investigate organized crime and official corruption are killed with impunity. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, more than 100 Mexican reporters, editors and photographers have been killed just since 2010. The 13 killed in 2022 represented an all-time high.

We hope López Obrador will grant us an interview, but we will continue to write about Mexican corruption and U.S. policy either way.