Years before Andrés Manuel López Obrador was elected as Mexico’s leader in 2018, U.S. drug-enforcement agents uncovered what they believed was substantial evidence that major cocaine traffickers had funneled some $2 million to his first presidential campaign.

According to more than a dozen interviews with U.S. and Mexican officials and government documents reviewed by ProPublica, the money was provided to campaign aides in 2006 in return for a promise that a López Obrador administration would facilitate the traffickers’ criminal operations.

The investigation did not establish whether López Obrador sanctioned or even knew of the traffickers’ reported donations. But officials said the inquiry — which was built on the extensive cooperation of a former campaign operative and a key drug informant — did produce evidence that one of López Obrador’s closest aides had agreed to the proposed arrangement.

The allegation that representatives of Mexico’s future president negotiated with notorious criminals has continued to reverberate among U.S. law-enforcement and foreign policy officials, who have long been skeptical of López Obrador’s commitment to take on drug traffickers.

The case raised difficult questions about how far the United States should go to confront the official corruption that has been essential to the emergence of Mexican drug traffickers as a global criminal force. While some officials argue that it is not the United States’ job to root out endemic corruption in Mexico, others say that efforts to fight organized crime and build the rule of law will be futile unless officials who protect the traffickers are held to account.

“The corruption is so much a part of the fabric of drug trafficking in Mexico that there’s no way you can pursue the drug traffickers without going after the politicians and the military and police officials who support them,” Raymond Donovan, who recently retired as the Drug Enforcement Administration’s operations chief, said in an interview.

In their investigation, DEA agents developed what they considered an extraordinary inside source after they arrested the former campaign operative on drug charges in 2010. To avoid federal prison, the operative gave a detailed account of the traffickers’ cash donations, which he said he helped deliver. He also surreptitiously recorded conversations with Nicolás Mollinedo Bastar, the close López Obrador aide who the operative said had participated in the scheme.

Along with the sworn statements of other witnesses, the taped conversations indicated that Mollinedo was aware of and involved in the donations by one of the country’s biggest drug mafias, current and former officials familiar with the case said.

But some officials felt the evidence was not strong enough to justify the risks of an extensive undercover operation inside Mexico. In late 2011, DEA agents proposed a sting in which they would offer $5 million in supposed drug money to operatives working on López Obrador’s second presidential campaign. Instead, Justice Department officials closed the investigation, in part over concerns that even a successful prosecution would be viewed by Mexicans as egregious American meddling in their politics.

“Nobody was trying to influence the election,” one official familiar with the investigation said. “But there was always a fear that López Obrador might back away on the drug fight — that if this guy becomes president, he could shut us down.”

Since taking office in December 2018, López Obrador has led a striking retreat in the drug fight. His approach, which he summarized in the campaign slogan “Hugs, not bullets,” has concentrated on social programs to attack the sources of criminality, rather than confrontation with the criminals.

Yet with police and military forces generally avoiding confrontation with the biggest drug gangs, those mafias have extended their influence across Mexico. By some estimates, criminal gangs dominate more than a quarter of the national territory — operating openly, imposing their will on local governments and often forcing the state and federal authorities to keep their distance. The violence has hovered near historic levels, while the gangs’ extortion rackets and other criminal enterprises have metastasized into every layer of the economy.

The Mexican president’s chief spokesperson, Jesús Ramírez Cuevas, did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

The drug trade’s toll on Americans has never been more devastating. Fentanyl — most of which is produced in or smuggled through Mexico — is fueling the most lethal illegal-drug problem in American history. The estimated 109,000 overdose deaths recorded in 2022, most of them fentanyl-related, surpassed the fatalities from gun violence and automobile accidents combined.

The administration of President Joe Biden has been steadfast in its refusal to criticize López Obrador’s security policies, avoiding confrontation even when the Mexican president has publicly attacked U.S. law-enforcement agencies as mendacious and corrupt. The fentanyl explosion, while a growing political concern in Washington, remains less critical to Biden’s reelection prospects than blocking immigrants at the southern border — a challenge in which López Obrador’s cooperation is essential.

After asserting repeatedly that Mexico had nothing to do with fentanyl, López Obrador has recently taken a few modest steps to renew anti-drug cooperation. His government, though, continues to ignore U.S. requests for the capture and extradition of major traffickers, while Washington officials portray the relationship in rosy terms. At the end of a meeting with López Obrador in November, Biden turned to him and said, “I couldn’t have a better partner than you.”

A Justice Department spokesperson declined to comment on details of the DEA investigation into López Obrador’s political campaigns, citing a long-standing policy. But she added that the department “fully respects Mexico’s sovereignty, and we are committed to working shoulder to shoulder with our Mexican partners to combat the drug cartels responsible for so much death and destruction in both our countries.”

For decades, U.S. law-enforcement officials have shied away from investigating Mexican officials suspected of protecting the drug mafias, saying that pursuing such cases is fraught in a country that is uniquely sensitive to American interference. U.S. agencies have been even more hesitant to dig into the gangs’ involvement in electoral politics, even as they have become a primary source of funding for Mexican campaigns and have murdered scores of municipal, state and national candidates.

In the case of López Obrador, the DEA was slow to act on information about his 2006 campaign’s possible collusion with traffickers, several officials said. When the agency finally began to investigate in 2010, it was largely at the initiative of a small group of Mexico-based agents working with federal prosecutors in New York.

The Americans’ initial source was Roberto López Nájera, a tightly wound 28-year-old lawyer who turned up at the United States Embassy in 2008 and asked to speak to someone from the DEA. The two agents who came down from their fourth-floor offices heard a compelling story: For the previous few years, López Nájera told them, he had been a sort of in-house counsel to one of Mexico’s more notorious traffickers, Edgar Valdéz Villarreal.

The Texas-born gangster had been nicknamed “Ken” and then “Barbie” when he was a square-jawed high school linebacker with dirty-blond hair. By the mid-2000s, he had become one of the Mexican underworld’s more brutal enforcers. He was also a major trafficker, working with a larger mafia run by the Beltrán Leyva brothers, who in turn were part of the alliance known as the Sinaloa Cartel. On the Mexican side of the border, he was known as “La Barbie.”

According to López Nájera, La Barbie insisted that he start at the bottom, washing the traffickers’ cars and doing other menial chores before he was entrusted with more important tasks. He eventually managed some political contacts, paying bribes to police commanders and politicians, and oversaw cocaine shipments through the Cancún airport. After several years, however, López Nájera began to have differences with his boss, who thought him something of a slacker, officials said. In 2007, he returned from a long vacation in Cuba to find that his brother had disappeared, an apparent victim of La Barbie’s wrath. Going underground, López Nájera began plotting his revenge.

López Nájera quickly established his bona fides with the Americans, telling them the Beltrán Leyva gang had planted a mole inside the embassy. The man turned out to be an employee of the U.S. Marshals Service who had wide access to intelligence about the Mexican criminals being sought by the United States. Lured to the Washington, D.C., area on the pretense of a training junket, he was arrested and charged with federal drug crimes before agreeing to cooperate, officials said.

The DEA moved López Nájera to the United States and debriefed him extensively. In keeping with the new law-enforcement partnership known as the Mérida accord, U.S. officials then invited their Mexican counterparts to interview their prized source.

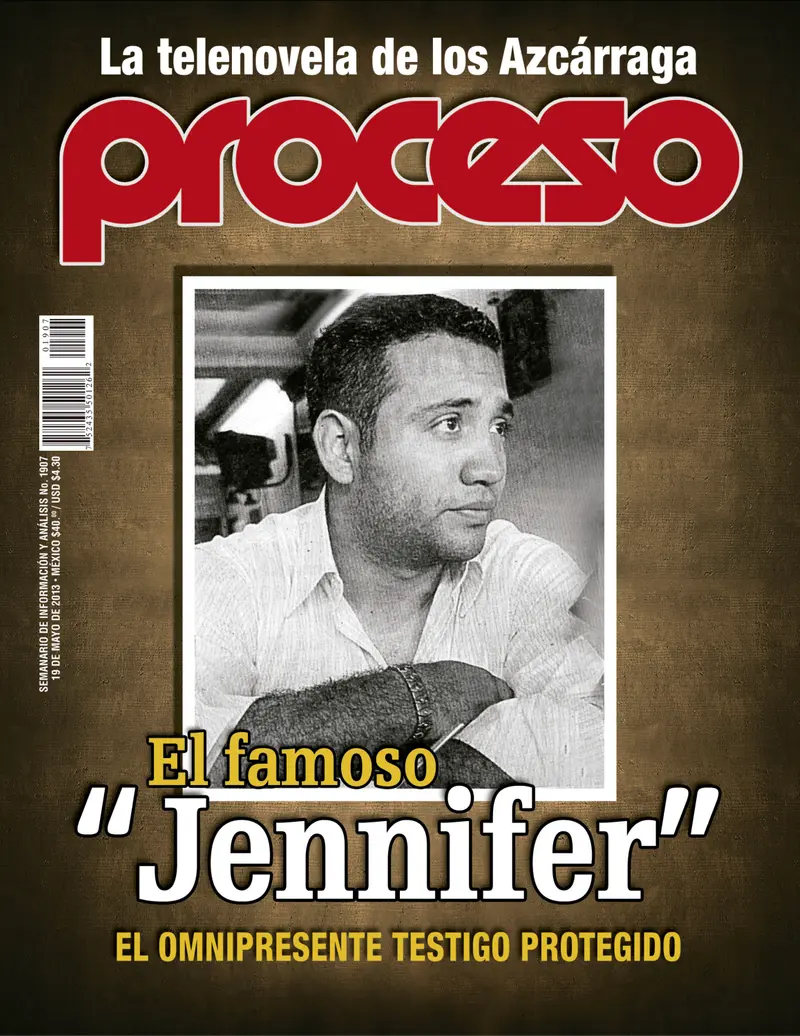

The Mexican court filings that resulted would identify López Nájera only by the code name “Jennifer.” His revelations would become the primary engine of “Operation Clean-up,” a headline-grabbing effort by the government of President Felipe Calderón to purge corrupt officials from federal law-enforcement agencies and the military.

The DEA was somewhat slower to take full advantage of its informer. It was only in the spring of 2010, more than two years after López Nájera had begun cooperating with the agency, that it began to focus on one of his more striking disclosures. In an interview in San Diego that DEA agents set up for a senior Mexican prosecutor, López Nájera described how La Barbie had summoned him to a January 2006 meeting at a hotel in the Pacific Coast resort of Nuevo Vallarta.

The man who had arranged the gathering was Francisco León García, the 38-year-old son of a mining entrepreneur from the northern state of Durango. Known as “Pancho” León, he was launching his candidacy for the Mexican Senate as a representative of López Obrador’s leftist alliance. He was friendly with one of La Barbie’s lieutenants, Sergio Villarreal Barragán, a towering former state police officer known as “El Grande,” and the two men thought they might be able to help each other, the agents were told.

Another businessman joined León at the meeting. The two said they were there with López Obrador’s knowledge and support, López Nájera recounted. In return for an injection of cash, León said, the campaign promised that a future López Obrador government would select law-enforcement officials helpful to the traffickers.

According to accounts of the negotiation that U.S. investigators eventually pieced together from several informants, the traffickers were told they could help to choose police commanders in some key cities along the border. More importantly, U.S. officials said, the traffickers were also told that López Obrador would not name an attorney general whom they viewed as hostile to their interests — seemingly granting them a veto over the appointment.

La Barbie agreed to the bargain and assigned López Nájera to meet with campaign officials in Mexico City and arrange the payoffs. (López Nájera did not respond to numerous attempts to contact him.) Soon after, officials said, he was introduced to Mauricio Soto Caballero, a businessman and political operative who was heading up an advance team under the campaign’s logistics chief, Nicolás Mollinedo.

In three deliveries over the next several months, the DEA was told, La Barbie’s organization gave Soto and others in the campaign about $2 million in cash. As the trafficker became more invested, López Nájera said, he provided support in other ways, too: Over the final weeks of the race, López Obrador traveled twice to the state of Durango for big, boisterous rallies organized by Pancho León, to which the gang donated heavily. One was so lavish — with a big-name band and thousands of partisans bused in from outlying towns and villages — that rival politicians demanded an investigation into León’s campaign funding.

The 2006 presidential race was a dead heat. When Mexico’s electoral tribunal declared Calderón the victor by half a percentage point, La Barbie was furious, López Nájera said. The drug boss came up with an impromptu plan to kidnap the president of the tribunal and force him to reverse the decision. A convoy of gunmen was dispatched to storm the court, turning back only when they discovered army troops guarding the area.

Having insisted he was the rightful winner, López Obrador rallied thousands of his supporters to Mexico City for a monthslong sit-in that covered a swath of the capital’s colonial center. According to López Nájera, La Barbie donated funds to help feed the protesters.

The DEA agents who heard López Nájera’s account understood that it would not be easy to build a criminal case, several officials said. Even if they could verify the allegations, high-level corruption cases were almost always hard to prove. Mexican officials used middlemen to insulate themselves from the traffickers who paid them. Politicians and criminals often protected one another; corroborating witnesses were usually reluctant to testify.

Most drug-related crimes also had a five-year statute of limitations. By the time the investigation got underway in earnest, some of the key events that López Nájera described had happened four years earlier.

The Mexican prosecutor who sat in on the López Nájera interview forwarded the allegations to more senior officials in Mexico City. But the Calderón government thought such a case would be too politically charged ahead of the 2012 election, former officials said.

DEA agents had better luck with the Southern District of New York, the powerful federal prosecutor’s office based in Manhattan. The head of the office’s international narcotics unit, Jocelyn Strauber, told them she thought the case was very much worth pursuing, current and former officials said. Strauber, who now leads the New York City Department of Investigations, declined to comment.

While the Southern District had rarely done Mexican drug-corruption cases, Calderón’s determination to work more closely with the United States gave the investigators some hope. U.S. agents had greater freedom to operate in Mexico than ever before; joint operations against traffickers had become commonplace. U.S. law-enforcement and intelligence agencies had helped the Mexican authorities arrest or kill leading figures of some big drug mafias, including the Beltrán Leyva organization. In May 2010, Mexico finally extradited Mario Villanueva, a former governor of Quintana Roo state, who eventually pleaded guilty in New York to funneling more than $19 million in traffickers’ bribes through U.S. accounts.

The investigators also recognized that López Nájera presented an unusual opportunity. Although he had been out of Mexico for more than two years, they thought he might be able to connect them to Soto, the former López Obrador campaign operative to whom he had delivered donations in 2006.

Soto was a gregarious, hustling business consultant with political ambitions of his own. He had worked in and out of government, finding angles and fixing problems with the bureaucracy. López Nájera said they had become friendly and that Soto had helped him with tasks unrelated to the campaign — acting as a front man for his purchase of an apartment in Mexico City’s tony Polanco neighborhood and helping him lease an office and renting a second apartment that La Barbie sometimes used on visits to the capital.

According to López Nájera, Soto had also introduced him to members of the 2006 campaign security team, connections that later proved useful when some of the men moved on to government security jobs. At one point, López Nájera recalled, Soto told him he might be interested in making money in the drug trade if the right opportunity arose.

With López Obrador preparing his second run for the presidency, Soto remained close to Mollinedo, who was still among the candidate’s most-trusted aides, officials said.

“Nico,” as Mollinedo was known, was something of a Mexican celebrity. Wherever López Obrador had gone during his five years as Mexico City’s mayor, Mollinedo had been beside him, at the wheel of the white Nissan sedan that López Obrador made a symbol of his contempt for the traditional excesses of Mexican politics. Mollinedo’s father had been a close friend and supporter of López Obrador’s since his days as a young activist in their native state of Tabasco.

Mollinedo had also been the subject of one of López Obrador’s first big political scandals, which erupted in 2004 with reports that the mayor’s driver earned the salary of a deputy secretary in the municipal cabinet. López Obrador brushed off “Nicogate,” as the newspapers called it, but made it clear that Mollinedo was much more than a chauffeur. He was the mayor’s personal aide and logistics coordinator and worked with his security team. Mollinedo acted as a sometime gatekeeper as well, filtering the people and proposals that clamored for the mayor’s attention.

By early 2010, a raft of Mexican officials had been arrested on López Nájera’s testimony, including a former top drug prosecutor and several senior police and military officials. His identity, though, remained a well-guarded secret, and he was confident that Soto believed he was still working for the narcos. They had last met in San Diego in late 2009, with DEA agents recording their conversation about whether Soto might want to get in on one of the drug deals López Nájera said he was putting together.

It made sense that López Nájera might be branching out on his own. La Barbie had stuck with the Beltrán Leyva brothers in what had been a two-year war with other factions of the Sinaloa Cartel. But now, as the Sinaloans gained the upper hand, La Barbie and the Beltrán Leyvas were fighting each other. The violence made headlines almost every day.

With the agents scripting his messages, López Nájera began texting Soto, officials familiar with the case said. In July 2010, they met at a hotel in Hollywood, Florida. Accompanied by an undercover DEA agent who posed as a Colombian cocaine supplier, López Nájera laid out his pitch: They had some deals in the works. They might need investors. The payoff would be big.

Soto said he was interested.

Weeks after the meeting in Florida, Soto flew to the Mexican-U.S. border to discuss a possible deal with the supposed Colombian trafficker and another undercover agent in McAllen, Texas. When he returned to McAllen in October, the two undercover agents told him they had 10 kilos of cocaine ready for him. But Soto balked, people familiar with the case said, insisting that he wasn’t ready to sell the drugs in the United States.

Needing some way to draw Soto back into their scheme, the undercover agents pressed him to safeguard the cocaine for several days until they could ship it to another buyer. As a reward, they would give him a kilo, worth about $20,000. The drugs were in a car parked nearby, one of the agents said, handing Soto a set of car keys. (There was no actual cocaine.) The conversation was recorded in its entirety.

Sometime after 2 o’clock the next morning, Soto returned to his room at a Courtyard Marriott. DEA agents were waiting.

On the wrong side of the border, without a lawyer or political connections, Soto did not take long to agree to cooperate. “He wasn’t the kind of guy who was ready to go to jail,” one official familiar with the case said. Later that day, after Soto waived his right to be prosecuted in Texas, he was flown to New York City on a commercial jet, sandwiched between a couple of agents in the back row.

Soto would thereafter become a confidential DEA source, known in the case file as CS-1. At the request of the DEA, ProPublica agreed not to identify him and other sources in the case. However, Soto was named in a Spanish-language article about the case published by DW News, the German state broadcast network.

After initially acknowledging messages from a ProPublica reporter, Soto did not respond to detailed questions about his role in the U.S. investigation.

Over several interviews with prosecutors from the Southern District, Soto confirmed that he had taken two deliveries of cash from López Nájera for the 2006 campaign and that a third delivery had been made by another envoy of La Barbie. Soto said the three contributions amounted to somewhat less than the $2 million that López Nájera had claimed, a discrepancy the agents attributed to customary skimming. Soto said he turned the money over to Mollinedo, people familiar with the case said.

In New York, Soto conferred with a court-appointed lawyer before agreeing to the government’s terms: If he continued to work secretly and speak truthfully with the investigators, he would be allowed to return to Mexico. His criminal conviction would remain sealed, and he would eventually be sentenced to the time he had “served” in federal custody — the several days he spent in McAllen and New York. Soto was brought before a federal judge and pleaded guilty to a single count of conspiracy to distribute cocaine.

U.S. officials understood that the arrangement posed serious risks. If Soto informed his colleagues in Mexico that he was being asked to set them up — or even if he just stopped returning phone calls — the Americans’ only leverage would be to expose his guilty plea and perhaps put out an international warrant for his arrest. But Soto would be able to expose their investigation.

The agents’ plan was to confirm the evidence they had gathered about the traffickers’ donations in 2006 and then to reenact a version of that scheme with López Obrador's incipient 2012 campaign — this time with recording devices in place. They called the investigation “Operation Polanco.”

To deploy Soto abroad as a covert or “protected-name source,” in the agency’s lexicon, the DEA had to submit its investigative plan to a group of Justice and DEA officials known as a Sensitive Activity Review Committee. A SARC (pronounced “sark”) is a screening process akin to a legal bomb squad. The panels examine undercover operations that involve the delivery of drugs or money to traffickers or the targeting of corrupt foreign officials; the lawyers try to deactivate the plans that might blow up on the department.

Although targeting the López Obrador campaign was an especially high-risk proposition, the SARC provisionally approved the plan in late 2010, officials said. The agents and prosecutors would have to return to the committee at least every six months for further review, and the scrutiny would intensify as they moved ahead.

The agents wanted to go big. They proposed offering the campaign $5 million in cash in return for promises that a López Obrador government would leave the traffickers alone. If Mollinedo or others in the campaign agreed, the agents would offer a down payment, maybe $100,000. They would then deliver the money to obtain hard evidence of the campaign’s complicity.

Some U.S. officials thought it was an auspicious moment for such a case. In August 2010, Mexican marines had captured La Barbie. Two weeks later, they took down El Grande, his lieutenant, who had attended the 2006 meeting in Nuevo Vallarta. Both men had been indicted on federal charges in the United States and, if extradited, might be enticed to cooperate in return for a reduction of their sentences. In a brief conversation after his capture, El Grande told a DEA agent he was willing to share information about corrupt Mexican officials, but only after he was moved to the United States, documents reviewed by ProPublica show.

But even as new pieces of the investigation came together, the Obama administration was growing concerned about the fallout from another undercover operation, what became known as “Fast and Furious.” Without informing Mexican officials, agents of the Justice Department’s Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives allowed hundreds of high-powered weapons to be shipped illegally into Mexico so they could track them into the hands of drug gangs. The tracking failed, however, and the weapons were later tied to shootings that killed or wounded more than 150 Mexicans as well as the murder of a U.S. Border Patrol agent. The Calderón government was outraged, and the tensions seemed to threaten bilateral cooperation once again.

“Things just came under a different level of scrutiny after Fast and Furious,” a former Justice Department official said. “At that point, everybody was in self-preservation mode.”

Still, American officials had some reason to hope that Mexico’s leaders might countenance — and keep secret — their investigation. Their ultimate target, López Obrador, was Calderón’s hated political rival. The DEA chief in Mexico City would inform the president’s intelligence chief, who was considered particularly trustworthy, and ask him to discuss the case only with Calderón.

The next phase of the investigation began well. DEA agents learned that the businessman who had accompanied Pancho León to the 2006 Nuevo Vallarta meeting was traveling to Las Vegas. When confronted by agents at the Bellagio Hotel & Casino, the businessman confirmed much of what Soto and López Nájera had said. He even mentioned a striking detail that López Nájera had noted: At the 2006 meeting in Nuevo Vallarta, León had given La Barbie a gift. Having heard that the trafficker collected watches, he brought a $20,000 Patek Philippe as a token of his respect.

The prosecutors initially thought they did not have enough evidence to arrest the man, so the agents let him return home after he promised to testify as a witness in any future criminal trial. The investigators had no hope of getting to León: In February 2007, months after losing his Senate race, he disappeared — the rumored victim of a drug-mafia murder.

In Mexico City, DEA agents rehearsed Soto, fitted him with a recording device and, in April 2011, sent him to talk with Mollinedo. It was a disaster. “He was terrified,” a former official recalled. Whether Soto mishandled the equipment or deliberately turned it off wasn’t clear, but he returned with a truncated recording that was often unintelligible because of background noise.

A second attempt the following month yielded about an hour of tape. It was clear from that conversation that Mollinedo knew about the 2006 transaction, people familiar with the case said. He seemed worried about two former members of the campaign security team, who had recently been jailed and might be pressured to reveal what they knew about the traffickers’ contributions. The officials said Mollinedo also mentioned friends in the Mexican attorney general’s office who might help protect him and Soto.

Although it was clear the two men were talking about the 2006 donations, Soto did not press Mollinedo to be more explicit or to incriminate himself more directly. “He never said, ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about’ or ‘I don’t know any of those people.’ There wasn’t anything said that cleared him,” one former official said of Mollinedo. “But the tape did not freshen up the conspiracy as much as was needed.”

In an interview, Mollinedo denied that he had ever received donations from drug traffickers and disputed the idea that López Obrador would ever tolerate such corruption. “We didn’t manage money,” he said, referring to his logistics team, adding that it only handled funds it was given to spend on transportation and other campaign expenses.

After going over the recordings, the New York prosecutors were underwhelmed, former officials said. For such a sensitive and risky case, they felt the evidence needed to be nearly irrefutable. The agents nonetheless proposed to move ahead with the sting operation directed at Mollinedo and other López Obrador aides. How they proceeded from there — and whether they went after López Obrador and other politicians in his orbit — would depend on what the agents learned.

When the SARC met to review the case again, just before Thanksgiving 2011, Justice and DEA officials in Washington, D.C., were joined by video link with senior DEA agents in Mexico City and New York. This time, however, the questions were sharper, several people familiar with the meeting said. Even if U.S. Embassy officials informed only trusted Mexican officials, the information could easily leak out, some officials said, and it could be explosive.

DEA representatives at the meeting emphasized that they were not seeking to affect the Mexican election, officials familiar with the meeting said. But they also made the point that if Mexico elected a president who came to office in debt to powerful drug traffickers, the consequences could be catastrophic for the two countries’ law-enforcement partnership.

Not long into the meeting, the video link to Mexico City went down — a common occurrence with the technology of the time. Without the main DEA group working on the case, the tone of the discussion shifted, two people present said. Justice Department lawyers talked about the huge risks of the operation, the uncertain evidence and the still-volatile aftermath of the Fast and Furious scandal, which had prompted some Republicans in Congress to call for the resignation of Attorney General Eric Holder.

The agents and prosecutors got word of the SARC decision days later — the operation was being shut down.

In May 2012, the Mexican government extradited El Grande. When agents were able to ask him on U.S. soil about the donations to the López Obrador campaign, he confirmed that La Barbie had made them after the meeting in Nuevo Vallarta, two officials said.

López Nájera’s star turn as Jennifer in Operation Clean-up was short-lived.

When the Calderón government was replaced in December 2012, it was not by López Obrador and his leftist alliance but by the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, the political party that had held the country in a corrupt, authoritarian grip for more than 60 years until 2000. The new president, Enrique Peña Nieto, quickly pulled back from his predecessor’s close law-enforcement cooperation with the United States. Part of that shift was an effort by Peña’s attorney general, Jesús Murillo Karam, to disparage and reverse the previous administration’s prosecutions of corrupt officials.

According to three officials familiar with the events, Mexican prosecutors continued to interview López Nájera in the United States, but now they sought to exploit gaps and contradictions in his testimony. They asked him to corroborate new details of events he had described, sometimes suggesting specific dates, only to have other witnesses produce alibis for the dates López Nájera had confirmed.

A flurry of Mexican news stories, many of them driven by apparent government leaks, assailed López Nájera as a well-paid liar for the previous regime. Proceso, the country’s leading investigative magazine, revealed his identity with a cover photograph that U.S. officials said came from the Mexican attorney general’s office. Virtually all the officials jailed in Operation Clean-up were released after the charges against them were dropped.

What did not become public was that U.S. law-enforcement officials took the opposite view. While they noted that López Nájera had been inconsistent or mistaken on some points in his statements, almost everything else he had told them held up. So even as López Nájera became a symbol in Mexico of the justice system’s failures, the DEA judged him credible and continued to work with him.

Even before López Obrador took office in December 2018, U.S. officials began to review information from the DEA investigation as part of their effort to assess the new president’s willingness to work with them against the mafias, people briefed on the effort said. But the new Mexican leader soon answered that question himself.

First he sidelined the Mexican commando teams that had been the most trusted partner of U.S. law-enforcement and intelligence agencies. He then shut down a federal police unit that the DEA had trained and vetted to work with the Americans on big drug cases.

When DEA agents arrested a former Mexican defense minister, Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos Zepeda, on drug-corruption charges in October 2020, López Obrador turned on the agency even more forcefully. With the military high command pressing the president to act in Cienfuegos’ defense, Mexican officials made clear that counter-drug cooperation was at risk. After U.S. Attorney General William Barr dropped the case and repatriated the general, López Obrador declared the Mérida accord “dead” and pushed through strict new limits on how U.S. agents could operate inside Mexico.

López Obrador’s long-standing promises to carry out a crusade against political corruption have produced almost no meaningful results. Although a smattering of corruption charges were announced early in the administration — nearly all against the president’s political adversaries — almost none were successfully prosecuted.

However, López Obrador did call into question the previous administration’s discrediting of Operation Clean-up. In August 2022, his government arrested Murillo Karam on charges of helping cover up the 2014 disappearances of 43 students in the state of Guerrero. Months later, the government announced that the former attorney general would also face corruption charges in connection with more than $1.3 million in hidden income and illicit contracts from which he was said to have profited during his time in office. Murillo Karam has denied the charges.

The president’s former close aide, Mollinedo, left López Obrador’s side after the 2012 campaign to go into business. He later joined Soto in trying to establish a new political party focused on the environment. The effort fizzled out within a year.

Mollinedo told ProPublica that he remains deeply loyal to the president. Although he and his family have been accused of growing wealthy from their political connections, he said his business endeavors have been entirely aboveboard.

Update, Jan. 31, 2024: At his regular morning news conference following the publication of ProPublica’s article, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador denounced the story as “completely false.” He added, “There is not a shred of evidence.”

He suggested that ProPublica’s story was a product of “management of the media” by the U.S. State Department and other powerful government agencies. “The DEA must say if this is true, not true, what was the investigation, what proof does it have.”