ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week. This story was co-published with Minnesota Public Radio and KARE-TV.

Amy Morris started working at Hilltop Health Care Center in Watkins, Minnesota, in June 2021 with a clean nursing license that belied her looming troubles.

Morris, a licensed practical nurse, had been fired from a nearby nursing home seven months earlier for stealing narcotics from elderly residents. The state of Minnesota’s health department investigated and found that the accusation was substantiated, and then notified the Board of Nursing, the state agency responsible for licensing and monitoring nurses.

But even though state law requires the board to immediately suspend a nurse who presents an imminent risk of harm, it allowed Morris to keep practicing.

In September 2021, supervisors at Hilltop discovered that pain pills were disappearing during Morris’ shifts and called the sheriff. Only then did Hilltop learn of allegations of narcotic theft that had been made nearly a year earlier at the other nursing home.

“I thought, ‘How is she practicing now?’” Meeker County Sheriff Brian Cruze recalled.

The answer, ProPublica found, is that the nursing board’s investigations frequently drag on for months or even years. As a result, nurses are sometimes allowed to keep practicing despite allegations of serious misconduct.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. In the face of intense criticism eight years ago, the nursing board announced changes to improve its performance. But that progress was short-lived, ProPublica found.

Since 2018, the average time taken to resolve a complaint has more than doubled to 11 months, while hundreds of complaints have been left open for more than a year; state law generally requires complaints to be resolved in a year. Some nurses, like Morris, have gone on to jeopardize the health of more patients as the board failed to act on earlier complaints.

Some of the board’s problems stem from vexingly bureaucratic issues, ProPublica found. For example, the board had started meeting every month to resolve cases more quickly. But, for the past few years, it has gone back to meeting every other month.

Some complaints get caught in a general email inbox, where they sometimes sit for weeks or months before being forwarded to staff for investigation, according to current and former staffers.

And the board, which oversees licensing and discipline for more than 150,000 nurses, has been perennially shorthanded. By state law, the board is supposed to have 12 nurses and four members of the public. But at times, it has operated with barely enough members to make up a quorum. In March, Gov. Tim Walz made five appointments to the board, leaving one vacancy.

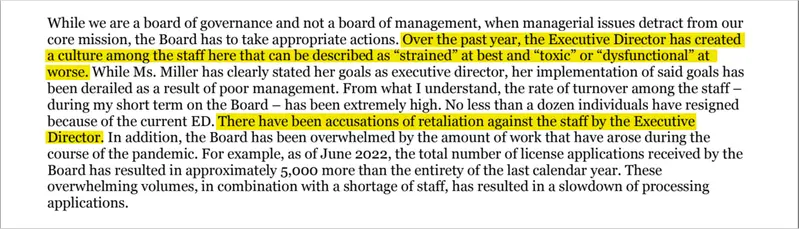

Other problems stem from the board’s professional staff, who investigate complaints and prepare the materials the board uses to make disciplinary decisions. Several former employees told ProPublica that the lag time in resolving discipline cases could be attributed to a dysfunctional office environment and a wave of resignations, many of them since the board’s August 2021 selection of veteran staffer Kimberly Miller as executive director.

David Jiang, who resigned from the board in August because he moved out of the state, told Walz in a letter that the board’s problems “arise because of a general lack of confidence from the staff, lack of communications to the board, and, most importantly, a general lack of oversight by the Board.”

Walz’s office did not respond to ProPublica’s requests for comment about Jiang’s concerns.

William Hager, a former legal analyst for the board, vented his frustrations about Miller’s leadership in an email to another employee in February 2022. “I am very concerned the Director seems to have been unaware of this ‘backlog,’” Hager, who left the board a few months later, said in the email. Miller “has chosen to not learn how to work” the case management system “or engage with software and staff to oversee our work.”

Miller, who worked for the board for more than two decades before becoming executive director, acknowledged the case backlog in an interview but said she was working to “right the boat,” including by hiring a consultant to improve board performance. Although the number of pending complaints is higher now than it was after a critical 2015 state audit, the backlog has been reduced by about a quarter since peaking last summer, according to state data.

“I think that we are on a good course at this point, and we’re making the changes that we need to, and learning to work as a team, and working out our system that I think is going to be really wonderful at some point,” Miller said in an interview. She did not respond to questions about criticism of her job performance.

Miller blamed the backlog on the transition to remote work during the height of the pandemic and on a new case management system that she said board members found difficult to use. She said some cases simply take longer than others. When a nurse won’t agree to discipline as part of a settlement, she said, the board must file the case in the state’s administrative court, where Miller said scheduling a hearing can take “at least a year.”

But a spokesperson for the administrative court said that the court was not the source of delays, and nurse discipline cases are concluded on average in four months from the time they are filed.

The state’s own data, in part, counters Miller’s assertions of progress. The board closed more complaints in fiscal years 2020 and 2021, respectively, than it did in 2022, when vaccines were widely available and many industries were returning to in-person work.

It was not clear why the board did not move quickly to suspend Morris after the substantiated report of pill theft. Miller declined to discuss individual discipline cases, citing confidentiality rules.

ProPublica contacted 10 current and seven former members of the board. None responded to requests for comment.

The nursing board finally issued a temporary suspension of Morris’ license in November 2021 — a month after prosecutors filed charges in the Hilltop case. She is facing felony theft charges for both incidents and has failed to show up in court. She has not entered a plea because she has not appeared to face the charges, and authorities have issued warrants for her arrest.

She did not return messages left on her cellphone and sent by email.

Administrators for both facilities declined to comment. Records show that one Hilltop manager was frustrated by a lack of warning about Morris. The manager complained to a state inspector that there was “nothing flagged on the background study or license verification,” according to the facility’s inspection report.

“This is not a facility system problem but a state system problem,” the manager said.

Investigations Drag On

When Christy Iverson started working for the board last year on investigations of nurse misconduct, she was surprised by the backlog of cases. Some she took on were around five years old. It was embarrassing, she said, to put her name on cases that had been on hold for so long.

Then, about four months into her tenure, she said, she was instructed to help the licensing staff with an influx of applications ahead of an anticipated nursing strike at several hospitals in the Twin Cities and Duluth areas. Iverson, who had spent over a decade working in leadership positions at an area hospital, said she largely spent her days folding letters and sorting paperwork. So she quit.

The problems she observed weren’t new. A Minneapolis Star Tribune investigation in 2013 had sparked the state audit that found serious delays at the board and led to improvements for a time.

With auditors scrutinizing it in 2014, the board began to dispose of complaints more quickly. The average age of closed cases was reduced from six months to four. But delays then climbed, eventually reaching the current average of 11 months, according to state data.

And despite a state mandate to resolve complaints within a year, the percentage of cases that go beyond that mark has soared from less than 5% in 2016 to 30% now, the state data shows.

Miller said the board is mindful of the backlog and puts a priority on “all of our more egregious cases.”

An internal email provided to ProPublica described how complaints can sit for weeks or even months simply because they weren’t forwarded in a timely manner. Those delays, the employee wrote, were “unprofessional” and “inefficient.”

For example, a complaint about a nurse stealing medication sat in the main inbox for more than two months before it was forwarded to the discipline staff, according to that internal email. It was the fourth complaint the board had received about that nurse. The employee’s email describing these delays was sent to several other employees and the board’s executive director in December. Miller did not answer ProPublica’s questions about the employee’s allegations.

Some delays begin in the earliest stages of processing a complaint, according to former employees and lawyers who represent nurses in front of the board. Eric Ray, a former discipline program assistant from January 2020 until fall of 2021, said in an interview that the board didn’t always meet statutory requirements to notify nurses of a complaint within 60 days of receiving it. Ray said he saw complaints “sitting for months or a year” before the board sent a notice to the nurse.

Miller said the board “did take seriously the 60-day issue” and recently made changes to the management software so that it would remind caseworkers that a letter needed to be sent out.

The notification delays can also hurt a nurse’s ability to mount a defense, according to lawyers who defend nurses in front of the board. As complaints age, they become more difficult to investigate, evidence becomes harder to locate, nurses move on to other jobs and witnesses forget key details.

“This is your professional career on the line,” said attorney Marit Sivertson. “It makes it incredibly difficult for someone to be able to fairly defend themselves.”

The state law that requires the board to resolve complaints within a year also gives the board sweeping discretion to take longer if it determines the case can’t be resolved in that time. Still, Sivertson said that does not explain why so many cases take more than a year to resolve. She and eight other lawyers have met several times to raise these issues with Miller and assistant attorney general Hans Anderson, legal counsel to the board. In October, they presented their concerns at a board meeting. They said they are still waiting for a response.

Del Shea Perry is also still waiting. It’s been nearly five years since the death of her son, Hardel Sherrell, in the Beltrami County Jail in northern Minnesota. The incident sparked public outrage and led to reforms and consequences for some of the officials connected to his care. Sherrell died on the floor of his cell after guards and medical staff refused his pleas for help. A pathologist hired by Perry as part of a wrongful death lawsuit later ruled that he died of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a treatable neurological disorder.

State legislators passed a law named after Sherrell that aims to improve access to health care for jail inmates. Todd Leonard, the jail doctor who monitored Sherell’s condition via telephone, had his medical license indefinitely suspended in early 2022. And this month, Beltrami County and Leonard’s company agreed to settle Perry’s lawsuit by paying Sherrell’s family $2.6 million.

But there have been no consequences for Michelle Skroch, a nurse who worked for Leonard and was directly in charge of Sherrell’s care in the last two days of his life. According to a state administrative judge who ruled in the doctor’s licensing case, Skroch failed to provide care to Sherrell or even check his vital signs as he lay nearly lifeless on the floor of his cell wearing adult diapers soaked in his own urine.

An emergency room doctor had released Sherrell to the jail with instructions to bring him back if his symptoms worsened. Instead, Skroch instructed jail staff not to assist him because she said there was nothing medically wrong with him, according to the judge’s report.

The judge wrote that it could appear from Skroch’s notes that she had “provided some type of care or assessment” of Sherrell. “She, in fact, did not,” the judge wrote.

Video later showed she had only briefly peered into his cell twice and had missed that he was in distress: Sherrell was unconscious on the floor with a white substance coming out of his mouth.

In response to Perry’s lawsuit, Skroch testified that she was able to sufficiently assess Sherrell’s condition without touching him and that she believed his condition was improving. She also noted that emergency room doctors had diagnosed him with weakness and “malingering,” a medical term for faking illness.

In ruling that the medical board had cause to discipline Leonard, the judge also called for the nursing board to investigate Skroch’s “dereliction of duty and shocking indifference.” Noting that the doctor was both Skroch’s supervisor and her romantic partner, the judge wrote it appeared “she was unconcerned about being held accountable by the attending physician.”

Five years later, Skroch still has an unblemished license and her online professional profile identifies her as the nursing director of Leonard’s medical firm. She declined to comment.

Another nurse who provided care to Sherrell at the jail filed an official complaint about Skroch with the nursing board. But she said that after an interview with a board representative about a year after the death, she has not heard an update. The board is required to provide updates every 120 days on the status of a case.

“I have no idea what the board is doing, and it sure as hell shouldn’t take 4 years to investigate,” Perry wrote in a text message.

“A Clear Message”

When a nurse is accused of misconduct, the board can seek discipline ranging from a reprimand, which is essentially a public slap on the wrist, to a license revocation, which means the nurse can no longer work in the field. Typically, the board allows a nurse to continue working while it tries to reach an agreement or takes the complaint to the state’s administrative court.

But in cases when the nurse poses an immediate risk to patients, the board can use its power to issue a temporary suspension and remove the nurse from practice while it investigates.

The board rarely used that power until the state legislature changed the law in 2014. Under the revised rules, the board wasn’t just authorized to use the emergency suspension — it was required to do so in cases where there was “imminent risk of serious harm.”

As a result, the board ramped up its use of temporary suspensions, issuing 55 of them from 2014 to 2017, more than twice as many as it had in the preceding four years, according to data reported to a national database of actions taken against medical professionals.

In 2018, this increase was touted by Daphne Ponds, then a board employee. Speaking at a national seminar on nurse regulation, Ponds, who helped investigate complaints against nurses, told her peers that the Star Tribune’s stories had “made us look bad, made us look ineffective.”

She added, “The legislature had really sent the board a clear message that you have this tool of temporary suspension — you need to use it.”

But about that time, the board had reverted to its pre-audit practices. In 2018, it issued only three temporary suspensions, according to a national discipline database. And it issued only 11 over the next three years.

Miller said the board is now inclined to protect the public by pursuing a voluntary agreement to stop practicing with nurses who’ve been the subject of a complaint. She said this is because there are “more hoops” to jump through to issue a temporary suspension, while the voluntary agreements can be drafted and signed by the nurse in days.

Asked how she reconciles this with a state law requiring a temporary suspension when there is an imminent risk of serious harm, Miller said Minnesota’s attorney general had signed off on the strategy.

Hager, the former legal analyst for the board, said that while a stipulation to cease practicing may work in some cases, it doesn’t work in all of them, especially when nurses don’t want to cooperate. In one case reviewed by ProPublica, a nurse kept her license for more than a year because she refused to sign a stipulation. The board suspended her only after she was convicted of financial exploitation.

Sometimes, the delays hurt patients. In early 2018, the board received complaints about a nurse named La Vang that accused him of stealing narcotics from patients — including one allegation that was validated by the state health department.

But the board didn’t issue a temporary suspension, and Vang got a new job later that year. He stole pain medicines from another patient, LaVonne Borsheim, according to a lawsuit that Borsheim and her husband brought against Vang and the home care company that employed him.

In that lawsuit, Borsheim described pain so severe that she didn’t want to go on living. (Attempts to reach Vang for comment were unsuccessful.)

By the time the nursing board got Vang to sign an agreement to cease practicing in August 2018, the police had already arrested him on charges that he had stolen Borsheim’s drugs. Vang pleaded guilty in federal court to obtaining controlled substances by fraud. At his sentencing, Vang’s attorney said he was in treatment for drug addiction and was embarrassed that he had violated Borsheim's trust. He was sentenced to 18 months in prison.