This article was produced in partnership with the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal, formerly a member of ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network, and The Marshall Project. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Three months after Mississippi’s Supreme Court directed judges in the state to ensure that poor criminal defendants always have a lawyer as they wait to be indicted, one of those justices acknowledged that the rule isn’t being widely followed.

“We know anecdotally that there’s a problem out there,” Supreme Court Justice Jim Kitchens said during a state House of Representatives committee meeting on the public defense system last week.

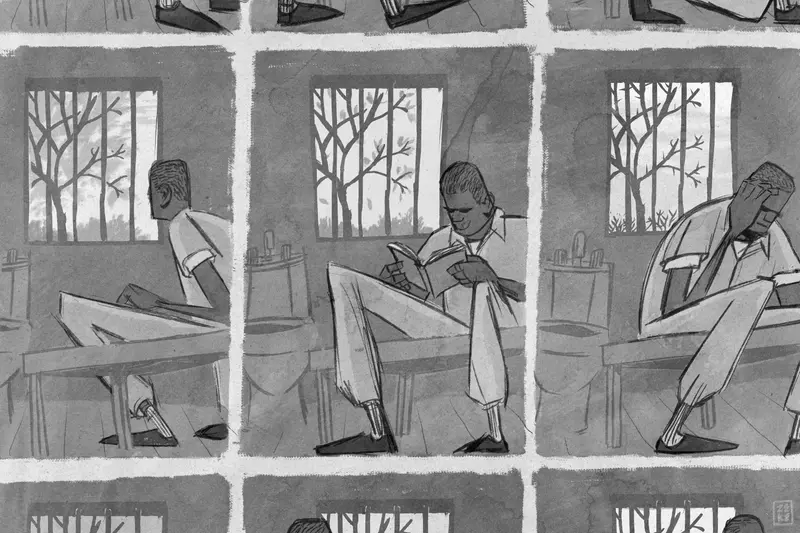

That means Mississippi’s “dead zone” — the period during which poor people facing felony charges are left without a lawyer while they await indictment — persists in many counties.

At the first court hearing after someone is arrested for a felony, a judge is supposed to decide whether the defendant can be released from jail and should appoint a lawyer if they can’t afford one.

In many Mississippi courts, that lawyer stays on the case for a short time to handle initial proceedings, including a possible motion for bond reduction, and then exits. Only after the defendant is indicted, which often takes months, is another lawyer appointed. In the meantime, no one is assigned to the case, even if the defendant is in jail.

“Mississippi stands alone as the only state that has this problem,” public defense expert David Carroll said at the state House hearing.

Carroll is the executive director of the Sixth Amendment Center, a nonprofit that studies state public defense systems and advocates for improvements. The center released a report in 2018 that found many defects in Mississippi’s public defense system, including the dead zone.

The Supreme Court’s rule, approved in April, was supposed to eliminate this problem. It says a lawyer can’t leave a case unless another one has taken over. All courts in the state must follow it.

Individual judges could face sanctions for not complying with the rule if someone files a complaint against them, Kitchens told legislators. Beyond that, however, Kitchens said it’s outside the purview of the Supreme Court to monitor local courts. “It’s not for us to go out and investigate whether that rule is being complied with,” he said.

When the rule went into effect in July, the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal, The Marshall Project and ProPublica found that many courts were unprepared to comply. Some local court officials were unaware of it. Others suggested that their practice of appointing lawyers for limited purposes would satisfy the rule, even though those attorneys do little beyond attending early court hearings.

State Rep. Nick Bain, a Republican from northeast Mississippi’s Alcorn County, convened the hearing on the weaknesses in the state’s public defense system. He also practices as a defense attorney in about 10 counties and regularly talks with lawyers who work around the state.

“There are wide swaths all over Mississippi where that rule is not being followed,” he said at the hearing.

In one circuit court district that did take action in response to the Supreme Court’s rule, there are signs that appointed defense attorneys are not doing much more than they did before.

In the 1st Circuit Court District, which covers seven counties in northeast Mississippi, chief Circuit Judge Paul Funderburk issued an order in July directing lower court judges in the district on how to meet the new requirements for indigent representation. He said an attorney in the lower court, where defendants first appear, must stay on the case until the defendant is indicted.

State Sen. Daniel Sparks, a Republican from Tishomingo County, represents those defendants in the county’s Justice Court, which hears misdemeanors and some early felony matters. He acknowledged that under the new Supreme Court rule and Funderburk’s order, he remains the attorney for indigent clients until they are indicted.

He said that although he will take calls from defendants and offer advice after they appear in justice court, he believes there is usually little defense work to do before an indictment. “I don’t think it changes my work dramatically,” he said of the Supreme Court’s rule.

He believes problems linked to the dead zone have been exaggerated by reform advocates.

Lee County Justice Court, based in Tupelo, is in the same circuit court district as Tishomingo. In July, the Daily Journal, The Marshall Project and ProPublica reported that the part-time appointed counsel for Lee County Justice Court, Dan Davis, typically did little more than file for a bond reduction for defendants who remained in jail for more than a month. After the new rule became effective in July, Davis told the court he didn’t want the job anymore.

Bill Benson, the administrator for Lee County, said last week that it’s not clear when a replacement will be available. “We’re trying to find someone who will stick with the defendants all the way through like the rule says,” Benson said.

Funderburk said he expects strict adherence to the new indigent defense rule and warned that courts “ignore it at their peril.”

Courts across Mississippi have ignored a broader rule regarding public defense, the Daily Journal, The Marshall Project and ProPublica have found. That rule, part of a 2017 push to standardize how courts across the state operate, requires judges to send to the Supreme Court their policy on how they fulfill their constitutional obligation to provide lawyers for poor criminal defendants. Just one circuit court district, covering three rural counties in southwest Mississippi, has complied.

“The counties need to come up with a plan,” Kitchens told lawmakers. “The justice courts, the circuit courts, the supervisors — all of them need to collaborate and come up with a plan.”

He called on lawmakers to fix problems with public defense that the Mississippi Supreme Court has been unable to remedy by imposing rules on local judges. The state is responsible for ensuring that its public defense system is adequate, he said. “The bottom line is the counties cannot do it alone.”

Bain, whose term ends in December after a primary defeat, said Mississippi must eliminate the dead zone and address other problems, including a lack of full-time public defenders and payment arrangements that encourage lawyers to cut corners.

“I think Mississippi is really stretching the limits of our constitutional obligations,” he said.