This article is a partnership between ProPublica, where Pamela Colloff is a senior reporter, and The New York Times Magazine, where she is a staff writer.

This story is exempt from our Creative Commons license until Oct. 9.

Sunny Eaton never imagined herself working at the district attorney’s office. A former public defender, she once represented Nashville, Tennessee’s least powerful people, and she liked being the only person in a room willing to stand by someone when no one else would. She spent a decade building her own private practice, but in 2020, she took an unusual job as the director of the conviction-review unit in the Nashville DA’s office. Her assignment was to investigate past cases her office had prosecuted and identify convictions for which there was new evidence of innocence.

The enormousness of the task struck her on her first day on the job, when she stood in the unit’s storage room and took in the view: Three-ring binders, each holding a case flagged for evaluation, stretched from floor to ceiling. The sheer number of cases reflected how much the world had changed over the previous 30 years. DNA analysis and scientific research had exposed the deficiencies of evidence that had, for decades, helped prosecutors win convictions. Many forensic disciplines — from hair and fiber comparison to the analysis of blood spatter, bite marks, burn patterns, shoe and tire impressions and handwriting — were revealed to lack a strong scientific foundation, with some amounting to quackery. Eyewitness identification turned out to be unreliable. Confessions could be elicited from innocent people.

Puzzling out which cases to pursue was not easy, but Eaton did her best work when she treaded into uncertain territory. Early in her career, as she learned her way around the courthouse, she felt, she says, like “an outsider in every way — a queer Puerto Rican woman with no name and no connections.” That outsider sensibility never completely left her, and it served her well at the DA’s office, where she was armed with a mandate that required her to be independent of any institutional loyalties. She saw her job as a chance to change the system from within. Beneath the water-stained ceiling of her new office, she hung a framed Toni Morrison quote on the wall: “The function of freedom is to free someone else.”

If Eaton concluded that a conviction was no longer supported by the evidence, she was expected to go back to court and try to undo that conviction. The advent of DNA analysis, and the revelations that followed, did not automatically free people who were convicted on debunked evidence or discredited forensics. Many remain locked up, stuck in a system that gives them limited grounds for appeal. In the absence of any broad, national effort to rectify these convictions, the work of unwinding them has fallen to a patchwork of law-school clinics, innocence projects and, increasingly, conviction-review units in reform-minded offices like Nashville’s. Working with only one other full-time attorney, Anna Hamilton, Eaton proceeded at a ferocious pace, recruiting law students and cajoling a rotating cast of colleagues to help her.

By early 2023, her team had persuaded local judges to overturn five murder convictions. Still, each case they took on was a gamble; a full reinvestigation of a single innocence claim could span years, with no guarantee of clarity at the end — or any certainty, even if she found exculpatory evidence, that she could spur the courts to act. One afternoon, as she weighed the risks of delving into a case she had spent months poring over, State of Tennessee v. Russell Lee Maze, she reached for a document that Hamilton wanted her to read: a copy of the journal that the defendant’s wife, Kaye Maze, wrote about the events at the heart of the case.

The journal began a quarter-century earlier with Kaye’s unexpected but much wanted pregnancy in the fall of 1998. Then 34 and the manager of the jewelry department at a local Walmart, Kaye had been unable to conceive in a previous marriage, and she was elated to be pregnant. Her husband, who shared in her excitement, accompanied her to every prenatal visit. But early on, there were signs of trouble, and Kaye was told she might miscarry. “I found out at four weeks that I was pregnant,” she wrote. “I was in the hospital two days later with cramping and bleeding.” The bleeding continued intermittently throughout her pregnancy, and she suffered from intense, at times unrelenting nausea and vomiting. She was put on bed rest, and Russell cared for her while also working the overnight shift at a trucking company. For the next six months, they hoped and waited, while Kaye remained in a state of suspended animation.

Eaton noted dates and details as she read. “After developing gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension and having low amniotic fluid, it was decided to induce labor at 34 weeks,” Kaye wrote. When she gave birth to her son, Alex, on March 25, 1999, he weighed 3 pounds, 12 ounces.

Alex spent the first 13 days of his life in the neonatal intensive care unit. Kaye and Russell roomed with him before he was discharged, taking classes on preemie care and infant CPR. Because he had been diagnosed with supraventricular tachycardia, or an unusually rapid heart rhythm, they were provided a heart monitor and taught to count his heart rate. The Mazes were attentive parents, Eaton could see. In the three weeks that followed his release from the hospital, they took him to doctors and medical facilities seven different times. When they took him to an after-hours clinic on April 18 to report that he was grunting and seemed to be struggling to breathe, a physician dismissed their concerns. “We were told that as long as we were able to console Alex, there was nothing wrong with him, except he was spoiled,” Kaye wrote. The doctor advised them, she continued, “that we, as new and anxious parents, needed to learn what was normal.”

It was the admonition — that they were too vigilant — that discouraged them from seeking medical attention when a bruise emerged on their son’s left temple and then his right temple. Another bruise appeared on his stomach. Russell worried that the tummy massage he had given his son to relieve a bout of painful constipation was to blame. “We are concerned,” Kaye wrote, “but trying not to jump at shadows.”

On May 3, Kaye left their apartment to buy formula. Half an hour later, Russell placed a frantic phone call to 911 to report that Alex had stopped breathing. He performed CPR until paramedics arrived. The baby was rushed to the hospital, where doctors discovered he had a subdural hematoma and retinal hemorrhaging; blood had collected under the membrane that encased his brain and behind his eyes. Preliminary medical tests turned up no obvious signs of infection or illness. With bruising visible on both his forehead and his abdomen, suspicion quickly fell on the Mazes. “We were told Alex had injuries that you only see with shaken baby syndrome,” Kaye wrote. A doctor who was called in to examine the 5-week-old for signs of abuse “told me she thought Russell hurt Alex.”

Eaton read the journal knowing that in the years since the infant was taken to the emergency room, shaken baby syndrome has come under increasing scrutiny. A growing body of research has demonstrated that the triad of symptoms doctors traditionally used to diagnose the syndrome — brain swelling and bleeding around the brain and behind the eyes — are not necessarily produced by shaking; a range of natural and accidental causes can generate the same symptoms. Nevertheless, shaken baby syndrome and its presumption of abuse have served, and continue to serve, as the rationale for separating children from their parents and for sending mothers, fathers and caretakers to prison. It’s impossible to quantify the total number of Americans convicted on the basis of the diagnosis — only the slim fraction of cases that meet the legal bar to appeal and lead to a published appellate decision. Still, an analysis of these rulings from 2008 to 2018 found 1,431 such criminal convictions.

When Alex was discharged from the hospital three weeks later, he had been removed from his parents’ custody and placed in special-needs foster care. The DA’s office charged Russell with aggravated child abuse. He was jailed that June and found guilty by a jury the following February.

Alex’s health continued to deteriorate, and on Oct. 25, 2000, over the Mazes’ emphatic objections, he was taken off life support. When Russell’s conviction was later vacated on a technicality, prosecutors charged him again, this time with murder. He was found guilty in 2004 and sentenced to life in prison. By the time Eaton examined the case, he had been behind bars for nearly a quarter-century.

She turned to the journal’s final entry. “My beautiful baby took 20 minutes to leave us,” Kaye wrote about the day of Alex’s death, when she was permitted to cradle him in the presence of his foster parents. “I held him in my arms, rocked him and sang him into Heaven. This is the most horrific thing for any mother to have to endure. The agony that my husband felt at not being allowed to be there is an agony no father should have to endure. What the state of Tennessee has taken from us can never be replaced or forgiven.”

Eaton understood that if she decided to take on the Maze case and concluded that Russell did not abuse his son, she was still looking at long odds. She would have to go before the original trial judge — a defendant with an innocence claim typically starts with the court where the case was first heard — to argue that the police, prosecutors and jurors got it wrong. That judge, Steve Dozier, was a no-nonsense former prosecutor and the son of a veteran police officer, who might be disinclined to disturb the jury’s verdict. But it was still early in Eaton’s investigation, and she did not know what she would find — only that she needed to first understand what persuaded jurors of Russell’s guilt.

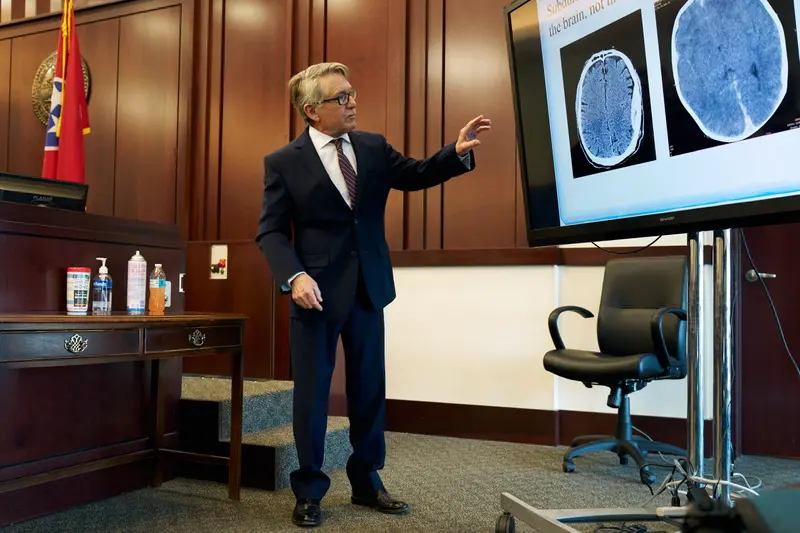

That evidence included testimony from the diagnosing doctor, Suzanne Starling, who told jurors that the bleeding around Alex’s brain and eyes indicated that he endured a ferocious act of violence by shaking. “You would be appalled at what this looked like,” she testified at Russell’s first trial. So forceful was the shaking, she added, that “children who fall from three or four floors onto concrete will get a similar brain injury.” Eaton also needed to make sense of a set of X-rays suggesting that Alex’s left clavicle had been fractured and a recording of an interrogation that prosecutors characterized as an admission of guilt.

When Eaton listened to the scratchy audio of Russell’s interrogation, she could hear the insistent voice of a police detective, Ron Carter, posing a series of increasingly combative questions. The investigator’s confrontational style had been considered good police work, Eaton recognized, but she observed that Carter would not take no for an answer when Russell denied hurting his child. Carter was mirroring what Starling told investigators; informed that the baby had been shaken, Carter predicated his questions on that seemingly incontrovertible fact. “You had to have shaken the child,” he told Russell. “That’s the only way it could’ve happened.” The detective repeated this idea more than a dozen times. Russell was already in a state of distress; he had just withstood four previous rounds of questioning at the hospital — from the treating physicians, Starling, another detective and a child welfare investigator — and he did not know if his son was going to live or die.

As Eaton studied the interview, she could see that Russell consistently denied harming his son. But he never asked for an attorney, and in unguarded comments, he sought to help the detective fill in the blanks of a situation that he himself did not seem to understand. He agreed that it was “possible” that while picking up Alex or putting Alex in a car seat, he had accidentally jostled the baby. “But as far as physically shaking him to the point of causing injury, no,” he said. Carter warned him that he was getting “deeper and deeper and deeper in trouble” and that his baby boy was “lying up there, and it’s for something that you caused.” The detective continued to insist that Russell was not telling the truth and that only he or Kaye could be to blame because they were Alex’s sole caretakers. Worn down, Russell finally hypothesized that he might have jostled, or even shaken, his son to try to revive him after finding him unresponsive. “I guess I could,” Russell said, sounding bewildered. “It’s possible.”

To Eaton’s ears, this did not amount to a confession. As she understood it, Russell was pressured to either accept blame or point the finger at his wife. He had remained steadfast that he did nothing to cause Alex to become unresponsive but found the baby that way.

The case did not look like the abuse cases she saw as a public defender; rather than hiding their son away, the Mazes put him in front of doctors again and again. But Eaton knew that once investigators and then prosecutors settle on the theory of a case, the state’s narrative calcifies, and DAs will go to great lengths to defend it. DA’s offices often reflexively reject innocence claims and even block defendants’ efforts to have the courts consider potentially exonerating evidence. Their faith in the underlying police work, and their certainty about a defendant’s guilt, can make prosecutors resist acknowledging a mistake. So, too, can the political pressure to protect the office’s record and to appear tough on crime. “It’s ingrained in some prosecutors to fight for the sake of fighting,” says Jason Gichner, the Tennessee Innocence Project’s deputy director, who now represents Russell Maze.

When Nashville created a conviction-review unit to try to disrupt this prosecutorial mindset, it was following the earlier lead of another reform-minded DA’s office. In 2007, Dallas’ newly elected district attorney, Craig Watkins, established what he called the conviction-integrity unit. The office he inherited had a long and ugly history of tipping the scales of justice against Black citizens, and Watkins wanted to harness the power of an innovative technology, DNA analysis, to see if he could undo some of the harms of that legacy. The unit reviewed hundreds of convictions in which defendants’ requests for testing had been denied. “When a plane crashes, we investigate,” Watkins told the Senate Judiciary Committee in 2012 when he testified about wrongful convictions. “We do not pretend that it did not happen; we do not falsely promise that it will not happen again; but we learn from it, and we make necessary adjustments so it won’t happen again.” By the time he left office in 2015, his conviction-integrity unit had exonerated 24 people, nearly all of them Black men. Since then the office has secured nine more exonerations.

Watkins’ vision for changing the system from inside inspired prosecutors in cities across the country to form their own conviction-review units. But because unraveling complex, long-ago criminal cases is labor-intensive, conviction-review units are unheard-of in the smaller, resource-strapped DA’s offices that dot rural America. Of some 2,300 prosecutors’ offices nationwide, just around 100 have them. In jurisdictions that have the funding and the political will for them — and where they are staffed not with career prosecutors but with attorneys who have defense experience — they can be powerful tools. According to data collected by the National Registry of Exonerations, these units have helped clear more than 750 people. Last year, they played a role in nearly 40% of the nation’s exonerations.

In the years that followed Russell’s murder conviction, doctors who challenged the notion that shaken baby syndrome’s symptoms were always evidence of abuse faced resistance from prosecutors. Brian Holmgren, who led the Nashville DA office’s child-abuse unit until 2015, and who tried the Maze case, built a national profile as one of the most strident critics. While a prosecutor, he served on the international advisory board for the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome, a nonprofit advocacy group, and he lectured around the country about how to conduct shaken baby prosecutions. He also was a co-author of two 2013 law-review articles, which lambasted doctors who testified for the defense in such cases as unethical and mercenary, suggesting that they were willing to offer unscientific testimony for the right price.

Holmgren made no secret of his disdain for these doctors when he delivered a keynote presentation at a National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome conference in Atlanta in 2010. Standing before an image of Pinocchio, he read from the testimony of physicians who had refuted shaken baby diagnoses, the puppet’s nose growing longer with each quote. He concluded his talk by inviting a guitar-playing pediatrician to lead the audience in a sing-along to the tune of “If I Only Had a Brain” from “The Wizard of Oz”:

I will say there is no basis for the claims in shaking cases,

My opinion’s in demand.

Though my theories are outrageous, I’ll work hard to earn my wages

If I only get 10 grand.

Holmgren’s impassioned advocacy on behalf of child victims made him a polarizing figure in Nashville. In 2015, The Tennessean ran a front-page article revealing that he told a public defender he would not offer a plea deal in a child-neglect case unless her client, who was mentally ill (she had stabbed herself in the stomach during one pregnancy), agreed to be sterilized.

His dismissal soon after was part of a sea change at the DA’s office that began in 2014, when voters elected Glenn Funk, a longtime defense lawyer, to be the city’s top prosecutor. As a sign of his commitment to reform, Funk created the conviction-review unit in late 2016, when CRUs were virtually nonexistent in the South. But for the first three years, it was by all measures a failure. Hamstrung by its own bureaucratic rules — a panel of seven prosecutors had to agree before any formal investigation could occur — the unit had yet to reopen a case. In 2020, Funk persuaded Eaton to come run the unit with assurances that she would not have to contend with the panel of prosecutors and that she would answer only to him.

Eaton needed qualified medical experts to evaluate the evidence in the Maze case, but she thought the public vilification of doctors might still give pause to one she wanted to talk to: Dr. Michael Laposata, who previously served as chief pathologist at Vanderbilt University Hospital in Nashville.

Laposata had spent much of his career recommending that physicians rigorously search for underlying diseases when evaluating children who are bruised or bleeding internally, rather than leaping to a determination of abuse. His body of work has shown that the symptoms of certain blood disorders can mimic — and be almost indistinguishable from — those of trauma. In 2005, he and a co-author wrote a seminal paper for The American Journal of Clinical Pathology, which acknowledged at the outset that child abuse too often goes undetected. But the fear among clinicians that they might inadvertently overlook a child’s suffering “has produced a high zeal for identifying cases of child abuse,” and that zeal, the paper argued, combined with a lack of expertise in blood disorders, had led to catastrophic mistakes. “It is very easy for a health care worker to presume that bruising and bleeding is associated with trauma because the coagulopathies” — disorders of blood coagulation — “that may explain the findings are often poorly understood.” Such a misinterpretation, the paper cautioned, could result in the false conclusion that a child had been abused.

Now the chief of pathology at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Laposata was initially guarded when the conviction-review unit asked if he would assess the Maze case, explaining that he was already overcommitted. He agreed to look at Alex’s lab reports and Kaye’s prenatal and birth records, but he made no promises that he could do more. His hesitance fell away after he reviewed the material. One fact leapt out at him immediately: Alex’s blood work was not normal. The infant’s hematocrit, or concentration of red blood cells, was not only extremely low; the size and shape of those cells were also atypical. This suggested a problem with red blood cell production that would have taken time to evolve, making it inconsistent with acute trauma. He put this into simpler language when he spoke with Eaton and her team, and she wrote down and underlined his words: “Abnormal red blood cells are not created from child abuse.” These abnormalities raised the suspicion of an undiagnosed blood disorder.

The pathologist also zeroed in on Kaye’s prenatal history. In addition to the health issues she enumerated in her journal, Laposata noticed a positive result for an antinuclear antibody test, commonly associated with an autoimmune disorder. Pregnant women with such disorders often develop antibodies and can pass them to the fetus, he explained. Those antibodies can remain in their infants’ systems for months and may lead to the formation of blood clots. He could see that the treating physicians did not conduct all the necessary tests to determine if Alex carried antibodies that would have predisposed him to clotting abnormalities. “It is surprising that these tests were never performed on the child given the extreme circumstances and the clinical implications of having a clot in the brain,” Laposata later wrote.

The likelihood that Alex suffered from an undiagnosed health condition raised serious questions about the prosecution’s case, and from that point on, Eaton did not look back; this was the conviction on which her team would focus. That there was a plausible medical explanation for Alex’s bruises also had profound implications for Kaye. Prosecutors had pointed to them as evidence that Kaye should have known her husband was abusing their son, and for failing to protect him, they charged her in June 1999 with aggravated assault. After she was told that having an open criminal case would make it harder to regain custody, Kaye took an Alford plea to a reduced felony charge — a plea that allows defendants to accept punishment while maintaining their innocence. She received a two-year suspended sentence and never regained her parental rights.

Eaton often thought about Kaye as she sifted through the case file. If Kaye had been willing to testify against her husband, she might have won back custody of her son, and in return for her cooperation, her criminal charge could have been reduced or dropped. Yet she always stood by Russell. She was unequivocal when she testified at his murder trial, insisting that he was not capable of hurting their child. She moved to rural East Tennessee after he was incarcerated there, so she could visit him as often as possible. She never abandoned their marriage. Eaton knew that such loyalty was rare; long prison sentences often lead to divorce, and the more time a person remains locked up, the more likely the marriage is to fall apart. Kaye’s resolute belief in her husband was not the kind of hard evidence Eaton was seeking, but she filed it away, another data point to consider.

Eaton had noticed a detail in the trial transcripts that she found telling: A police officer named Robert Anderson testified that when he arrived at the apartment as paramedics worked to revive Alex, he saw Russell looking on, impassive. He was acting “rather calmly, just kind of watching,” Anderson told the jury. “He didn’t appear upset, no, not from the outside.” The inference was that Russell was callous, even cold-blooded.

Eaton, having followed the emerging research on trauma, saw something different in his emotionlessness. The encounter with police came just after Russell struggled to resuscitate his son, who had turned blue and gone into cardiac arrest. She was struck by how little the investigators who first interacted with the Mazes understood acute stress and how much that lack of knowledge shaped the investigation that followed.

Eaton had educated herself about the effects of trauma because it had altered not only the lives of her defense clients but also her own. She arrived in Nashville during a tumultuous adolescence, after running away from home in Clarksville, Tennessee, at the age of 16. “I’d experienced a significant trauma, and I didn’t know how to ask for help,” she told me. She was from a peripatetic military family that was not equipped to give her the intensive support she needed. In a Nashville phone booth, Eaton spotted a sticker that read, IF YOU ARE A TEENAGER AND YOU NEED HELP, CALL THIS NUMBER. She dialed the number and, weeping into the receiver, said she had nowhere else to turn.

That phone call, Eaton believes, saved her life. It led her to an emergency shelter for teenagers, where she found counselors who were trained in crisis intervention, and after receiving daily therapy, she returned to Clarksville to finish high school. From that point forward, she knew she wanted to go into a helping profession — a journey that led her first to psychology and then to the law. She was drawn to representing defendants, whom she saw as survivors of trauma too. “No 5-year-old dreams of growing up to become a felon,” she told me. She joined the public defender’s office in 2007, and squaring off against the DA’s office day after day, she proved to be both quick on her feet and tenacious. Three years later, she started her own private practice.

Funk, the district attorney, had always regarded her as one of the brightest stars in Nashville’s criminal defense bar, and as his conviction-review unit foundered, he began talking to her in 2019 about taking the helm. He knew that if he wanted to make the unit effective, he had to put someone with her singular focus and defense experience in charge. Nashville’s CRU was not the only one to fall short of expectations; many conviction-review units have not produced an exoneration. Some are simply overburdened and underfunded, while others have met resistance from local judges. But underperforming conviction-review units have also given rise to suspicion, among defense attorneys, that there is a more cynical calculus at work; they see DAs who want to signal their commitment to justice reform without actually doing the hard work of challenging fellow prosecutors and local police officers.

“The C.R.U., as presently constituted, is a complete and utter sham,” the defense lawyer Daniel Horwitz wrote in 2018, when the Nashville DA’s office declined to act on new information that his client, convicted of murder, was the wrong man.

In Funk’s willingness to try to do better, Eaton saw an opportunity to give defendants with credible innocence claims a fair hearing, while using the resources of the state to investigate. The first case she took on, in the summer of 2020, was Horwitz’s client, Joseph Webster. Tennessee law does not give prosecutors any clear mechanism to get back into court if they uncover a potential wrongful conviction. Eaton coordinated with Horwitz, who had already obtained DNA testing of the murder weapon and tracked down eyewitnesses to the killing whom the police had ignored. After conducting her own independent investigation, which built on two years of work by her predecessor, she went to court to jointly argue with the defense that Webster should walk free. His conviction was vacated, and he was released, having served nearly 15 years of a life sentence.

This became the template for how Eaton worked. Conducting her own parallel investigations alongside the Tennessee Innocence Project, she probed more troubled cases. Of the five convictions she helped undo, three relied on forensic findings that are now seen as flawed.

One of those defendants, Claude Garrett, had already spent nearly 28 years in prison when Eaton began looking at his case in 2020. He survived a 1992 house fire only to be charged with murder after fire investigators determined that the blaze, which claimed the life of his fiancée, was intentionally set. He was locked up when his daughter was 5 years old. In the intervening years, many once-accepted tenets of arson science were debunked. The “pour patterns,” or burn marks, that arson investigators saw as proof that someone poured an accelerant around the house had come to be understood as a natural byproduct of fast-burning fires. Several nationally recognized fire experts who reviewed the case testified that there was no evidence the fire was intentionally set. “When stripped of demonstrably unreliable testimony, faulty investigative methods and baseless speculation,” Eaton wrote to the court, “the case against Garrett is nonexistent.”

Garrett’s conviction was vacated, and he was released in May 2022 at the age of 65. He died suddenly, five months later, of heart failure. “When we have advancements in science, why don’t we look at every single case in which that science convicted someone and see whether the evidence still stands up?” his daughter, Deana Watson, says. “People are going to die in prison who don’t belong there — human beings who literally have no reason to be there, who are stuck there based on what we thought was true 30 years ago.”

Claude Garrett’s death would always hang over Eaton — a nagging reminder, as she worked on the Maze case, that there was no time to spare. She and Hamilton, who was a former federal defender, threw themselves into their reinvestigation. The lawyers learned about blood disorders and genetic diseases, poring over medical journals and buttonholing doctors. They spoke to experts about police interrogation techniques and the effects of emotional trauma on suspects. They visited the Mazes’ former apartment complex to visualize the sequence of events. They conferred with lawyers at the Tennessee Innocence Project, who were talking to other medical experts around the country. Still, the question remained: What had happened to Alex?

Eaton wanted to stay focused on the specifics of Alex’s case and not get lost in the controversy over shaken baby syndrome. While there is no disagreement that the violent shaking of an infant causes harm, there is fierce dissent over whether the symptoms associated with the diagnosis can be taken as proof that abuse has occurred. (“Few pediatric diagnoses have engendered as much debate,” the American Academy of Pediatrics acknowledged in a 2020 policy statement.) This has left both doctors and the courts divided. Over the past four years, according to the National Registry of Exonerations, nine people whose convictions rested on the diagnosis — five parents and four caregivers — have been exonerated. Last year, a New Jersey appellate court backed a lower-court judge who pronounced the diagnosis “akin to junk science.” But appellate judges in recent years have also upheld shaken baby convictions, including that of a man on death row in Texas, Robert Roberson, whose execution date is set for October.

Eaton reached out to experts in the fields of pathology, radiology, neonatology, genetics and ophthalmology, and over the spring and summer and then fall of 2023, physicians who looked at the medical records independently of one another came to the same conclusion: Alex’s symptoms were not consistent with abuse. They observed that the bleeding in his brain and around his eyes continued to progress during his hospitalization. Such ongoing hemorrhaging “suggests a mechanism other than abusive trauma,” explained Dr. Franco Recchia, an ophthalmology specialist. So, too, did the increased bleeding around Alex’s brain. The doctors were in agreement: This progression of symptoms pointed to an undiagnosed, underlying condition — like a metabolic disease or blood disorder — which most likely resulted in a stroke. After reviewing the autopsy slides and other medical records, Dr. Darinka Mileusnic-Polchan, the chief medical examiner in Knox and Anderson counties, determined that Alex “had a systemic disorder that was never properly worked up due to the early fixation on the alleged nonaccidental head trauma.”

The doctors noted the absence of obvious evidence of violence; Alex had no neck injuries, broken ribs, limb fractures or skull trauma. They also zeroed in on what Eaton and Hamilton found noteworthy in Alex’s hospital records: Starling rendered her diagnosis within hours of Alex’s arrival at the ER, before receiving all the results of blood work and other testing. And she did not consult his pediatrician’s records, which documented a sudden increase in his head circumference weeks before he arrived at the emergency room. (Starling did not respond to requests for comment.)

But it was the analysis of one last piece of evidence, a set of X-rays known as a skeletal survey, that helped Eaton understand something that she had been trying to make sense of, but that had remained stubbornly perplexing: the clavicle fracture. A close examination of the medical records showed that chest X-rays, performed when Alex was first admitted to the emergency room, did not detect any breaks. Only after he was diagnosed with shaken baby syndrome was a fracture identified on the skeletal survey, on his second day in the hospital.

Interpreting radiological images like a skeletal survey can be subjective, and when evaluating a curved bone like the clavicle, radiologists may disagree about whether a tiny abnormality is a fracture or not. When Dr. Julie Mack, a Harvard-trained radiologist, reviewed the images last fall for the Tennessee Innocence Project, she said she saw no evidence of a bone break. She left open the possibility that a slender hairline fracture was present, which she could not detect in her copy of the original images. But, she explained, “He underwent CPR, which, if a clavicle fracture was present, is a sufficient explanation for such a fracture.” Mack’s review of the records, which included several CT scans and an MRI of Alex’s brain, led her to conclude that the infant had suffered not from abuse but rather from “an ongoing, abnormal, natural disease process.”

In coordination with the conviction-review unit, Russell’s attorneys filed a motion in state court in December, seeking to reopen State of Tennessee v. Russell Lee Maze. “Physicians who suspect abusive head trauma can no longer stop their analysis with the identification of the shaken baby syndrome triad,” it read. “Instead, they must seriously consider all other etiologies that may plausibly explain the constellation of symptoms and eliminate them as causes.” Horwitz — the attorney who once called the CRU a sham — and one of his law partners, Melissa Dix, also filed a motion on behalf of Kaye, petitioning the court to vacate her felony conviction. The decision about whether to reopen the case was in the hands of the judge, Dozier; he had been on the bench since 1997, having won reelection or run unopposed in every election since his appointment.

Eaton walked over to the courthouse that day with Hamilton to file the unit’s 71-page report, which detailed their investigation. Eaton and her team wrote a report each time they went before a judge to ask that a conviction be overturned. It was imperative, she believed, to establish trust with judges before asking them to take the weighty, and sometimes politically perilous, step of tossing out a jury’s verdict, and to signal that they had the full backing of the DA’s office. “While it was reasonable for the treating doctors to consider abuse,” the report read, “every other medical possibility was either overlooked or completely ignored. Law-enforcement officers blindly followed the course set out by Dr. Starling and failed to consider any other explanation for Alex’s condition. After an investigation comprised of a hasty medical determination, an interrogation of traumatized parents and little else, the case was considered closed.”

The lawyers recommended that the court vacate Russell’s and Kaye’s convictions. “The tragedies in this case cannot be overstated,” they concluded. “What every single expert the C.R.U. consulted with agrees upon is that Alex Maze did not die from abuse.”

Shortly after they filed their report, Dozier agreed to set a hearing so that he could evaluate the findings from the state’s and defense’s expert witnesses.

When Russell was led in handcuffs into the courtroom on a drizzly morning this past March, he bore little resemblance to the ruddy-cheeked new father paramedics found in 1999, struggling to revive his infant son. At 58, his careworn face was framed by thick, prison-issued glasses. He walked with a cane, which he had to maneuver with both hands manacled together, and as he took his seat at the defense table, he winced. Beside him sat Kaye, her expression guarded, her shoulder-length hair shot through with gray. The husband and wife, who last lived together when Bill Clinton was president, were instructed not to have physical contact. Wordlessly, they gazed out at the courtroom and waited for the hearing to begin.

Eaton had not slept well. She knew that the experts who were slated to testify would be good witnesses, but she worried that their testimony would not be enough to satisfy Dozier. It was Dozier who signed off on Kaye’s plea deal and Dozier who presided over not only Russell’s trials but also his appeals and postconviction proceedings. It was Dozier who sentenced Russell to life in prison.

She studied him as he sat on the dais before them, quietly conferring with his clerk, and tried to read his mood. Eaton appeared before him when she was a public defender, and she was well aware of how tough he could be. But some of her biggest victories came in his courtroom, including the Joseph Webster case, her first exoneration. That case had included the persuasive power of DNA evidence, something she was painfully aware, at that moment, that the Maze case lacked.

The state’s opening statement would be delivered by Funk. District attorneys seldom appear in court to throw their weight behind their prosecutors, but both Funk and Eaton thought it would send the right message to Dozier. Funk struck a note of deference as he underscored his support of the CRU’s findings, playing not to the local TV news cameras in the courtroom but to an audience of one. “Every single medical expert, using current science, confirms that Russell and Kaye Maze are actually innocent of the crimes for which they were convicted,” he told the judge. “It is my duty as district attorney to ask the court to vacate these convictions.”

But Dozier appeared unreceptive from the start. When Russell’s lead attorney, Jason Gichner, gave his opening statement outlining the defense experts’ findings, Dozier grew impatient, interjecting, “Do they factor in that there’s a history of a statement that the child was jostled?” When it was time for the physicians to testify, he remained obstinate. He grilled them about granular aspects of their testimony, repeatedly breaking in to interrogate them and questioning whether their opinions were grounded in any kind of new scientific thinking. He wondered aloud if different experts, evaluating the same evidence, might reach a completely different conclusion. Even when he said nothing, he radiated disapproval; he arched his eyebrows, pursed his lips and shot exasperated glares at whoever was sitting in the witness box. He grew more skeptical as the hearing went on, accusing Russell’s attorneys of only presenting experts who had been “picked and chosen” to best suit the defense’s narrative.

During breaks, the lawyers conferred with one another, unsure how to interpret the judge’s intransigence. Dozier was always prickly, and in the absence of an adversarial party, he seemed to have decided to take on the role of adversary himself. Perhaps the judge was just putting them through their paces, pushing back on them to elicit answers that would only strengthen their arguments. Or maybe, Eaton feared, they had lost him. For months, her team worried that Dozier would balk at the fact that their experts had not coalesced around a single diagnosis that could explain all of Alex’s symptoms, and yet without new blood and tissue samples to test, it was all but impossible to agree upon a definitive cause of death. When she called Dr. Carla Sandler-Wilson, a neonatologist, to the stand on the second day of the hearing, she had the doctor inform the court that newborn screening tests — which can identify genetic, blood and metabolic abnormalities — were so limited at the time of Alex’s birth that he was screened for just four disorders. “There are over 50 tests on the Tennessee State Newborn Screen now,” Sandler-Wilson explained.

The Mazes remained composed throughout hours of graphic testimony about the condition of their son’s body and the details of his autopsy. All told, seven experts from around the country took the stand to attest to the fact that Alex’s symptoms resulted from natural causes, not trauma.

In the weeks leading up to the hearing, Eaton had written and rewritten her closing argument. She paced her house for hours, practicing until she could recite it from memory. She rehearsed it in the shower, and in her car, and in the quiet of her home office. She delivered it for friends and colleagues so she could gauge whether the most important lines were resonating, and she recited it to her therapist. Her closing argument was a very different narrative from the one prosecutors presented at trial. “If Alex Maze could speak to us,” the argument she had prepared began, “he would tell us his parents loved him, cared for him and, to his last breath, did not give up on him.”

As Eaton watched Gichner deliver his closing argument, which Dozier cut into with rapid-fire questions, she realized that she needed to change course. An emotional plea was not going to win the judge over. She set aside the speech she knew by heart. She would have to improvise.

When her turn came to speak, Eaton rose and walked across the courtroom to face the judge. Gripping the lectern, her face rigid with concentration, she tried to find the right words. “Our office receives hundreds of applications for review per year,” she began. “Out of those hundreds, we take on less than 5%. And of that 5%, sometimes we have to ask experts to review the information in the case.” She continued: “We’ve had experts look at cases and tell us, ‘No, you got this right — this was trauma, this was abuse.’ And we turn down those cases. But sometimes, your honor, a case is different.”

She spoke quickly, as if by racing forward, she could prevent the judge from interrupting her. “Over the last two years, this unit has analyzed every detail of this case,” she said. “We’ve read every record. Every line of testimony. We’ve consulted expert after expert. And we did not just rely on the petitioner’s experts. We got baby Alex his own independent experts, including the chief medical examiner for Knox and Anderson county, who more typically testifies for the state. Including a local practitioner trained at Vanderbilt, who we trust with our babies every single day. Including the former chief pathologist for Vanderbilt University. And one by one, expert after expert, told us this was not abuse —”

Dozier leaned forward in his high-backed chair. He wanted to know about the doctor who had diagnosed Alex with shaken baby syndrome, Starling, and whether she had been consulted. “But she wasn’t?” he asked sharply.

Eaton was startled by the question because it showed a fundamental misunderstanding of the work that the conviction-review unit did. Her duty was not to double-down on the state’s original trial theory but rather to investigate whether there was new evidence to consider, and whether that evidence was consequential enough that it should change the outcome of the case. Just as she did not ask the original prosecutors to evaluate the soundness of the conviction, so she did not ask Starling to review the accuracy of her diagnosis. Eaton had sought out physicians who did not have a record to defend.

“No, she was not,” Eaton said. “But we consulted experts in every possible field that could be relevant to this case. And one by one, they told us that the science presented to this court was outdated. One by one, they told us that our understanding of things has changed. And one by one, they told us that Russell and Kaye Maze did not abuse their son, and they did not cause his death.” She looked directly at the Mazes as she spoke. Then she turned to the judge and raised her voice to signal the importance of the point she wanted to make, drawing out each word: “The state got this wrong.”

When she finished, Dozier offered no reaction as he looked down from the dais. “All right,” he said flatly. “I will take this under advisement.” Court was adjourned for an indeterminate period of time — as long as it took for him to make his ruling. There was nothing more to do but wait.

A few days after the conclusion of the hearing, the two prosecutors who originally tried the case wrote to the court voicing their opposition to the effort to clear Russell Maze. Brian Holmgren and Katrin Miller expressed outrage that they had learned of the hearing only from local media coverage, and they pushed back against the notion that the science behind shaken baby syndrome had grown weaker in recent years. That idea had been promulgated, they asserted, by a “small cadre of medical witnesses” and shaken baby “denialists.” They went on to suggest that the push to exonerate Russell was part of a concerted, nationwide campaign to discredit the diagnosis. The hearing, they wrote, had given “denialist medical witnesses another opportunity to publicize their false scientific claims.”

Dozier informed the two lawyers that they could not insert themselves into the proceeding, and he denied them the opportunity to file a brief with the court that would have formalized their opposition. He did not, however, hand down his ruling. One week passed, then two. A third week came and went without any word. As the days dragged on, Eaton had trouble focusing. Briefly, she entertained a bit of magical thinking; maybe the judge was drafting such a sweeping ruling in the Mazes’ favor that it was just taking him a little extra time. She stared at her phone, checking her messages again and again. “I’m worried,” she told me on April 23. “I’m worried for Russell. I’m worried for Kaye. I’m worried for the morale of my team and worried that if we lose this case, it will make it a million times more difficult to help anyone else.”

Two days later, Eaton was working on her laptop when she spotted an email from the court. She could see that it landed in her inbox a half-hour earlier. The silence of her phone — no calls, no texts — signaled bad news.

The decision leaned heavily on the findings at Russell’s preceding trials. “Substantial evidence presented at two trials is not sufficiently overridden by the new scientific evidence,” it read. Dozier did not give the witnesses’ testimony at the hearing any more weight than the original testimony of witnesses like Starling. The present-day testimony did not represent a new scientific consensus; in the judge’s estimation, it was nothing more than “new ammunition in a ‘battle of the experts.’” He went on to find fault with the hearing itself, which he criticized for lacking “the adversarial role of the prosecutor” — a weakness, in his eyes, that rendered experts’ testimony less credible. With no opposing counsel to cross-examine the witnesses, he argued, “fresh opinions were offered but not probed.” Ultimately, Dozier wrote, “The court does not find an injustice nor that the petitioner is actually innocent based on new scientific evidence.”

Bewildered, Eaton tried to grasp what she had just read: The judge was penalizing them because everyone — the state, the defense, the witnesses — agreed that the Mazes committed no crime. As she wrestled with the implications of the ruling over the days that followed, she began to ask herself increasingly absurd questions. By the judge’s logic, should she have been performatively combative with the defense’s witnesses? Would Russell have stood a better chance if the DA’s office had fought the defense’s efforts to prove his innocence? Did the “adversarial role of the prosecutor” leave no room for the state to right a wrong — or worse, did it require prosecutors to uphold a bad conviction? Dozier’s ruling went to the heart of what a conviction-review unit is supposed to do, and it seemed to eviscerate it.

Never had there been a day, since taking on the Maze case, when Eaton did not know that losing was a possibility. But the implications of Dozier’s ruling made her worry for the future — both for the chilling effect it might have on other judges at the courthouse and, more broadly, for the system as a whole. Her own office filed the original criminal charges against the Mazes, but the same office could not undo them. If the DA’s office could not fix this, who could?

Russell remains one of many defendants who have been behind bars for decades based on the testimony of expert witnesses who believed in the inviolability of shaken baby syndrome. In April, Starling — who, by her own account, has testified in court more than 100 times — was a state witness at a hearing for a case in Atlanta that was similar to Russell’s. Danyel Smith, who was convicted in 2003 of the shaking death of his 2-month-old son, was asking for a new trial, asserting that the infant died from trauma sustained during childbirth. Starling, who was not involved in the original prosecution, testified that the only explanation for the baby’s symptoms was abuse. During cross-examination, Starling was asked about Tennessee v. Maze. “I’m not familiar with this case,” she told Smith’s attorney. The lawyer then produced hundreds of pages of testimony bearing her name. “That does prove that I was there,” she allowed. But the facts of the case had escaped her, she said. “If you say he was convicted, then I will take you at your word.”

“He has served 25 years in prison?” the lawyer pressed.

“Again, not in my personal knowledge,” she replied.

Russell’s case is currently before the Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals, which must decide whether to grant him permission to appeal the ruling. “The Tennessee Innocence Project fully believes in Russell’s innocence, and we will not stop fighting until he is released from prison,” Gichner told me. (Kaye’s appeal to vacate her felony conviction will proceed separately.) The case now faces a new challenge: Lawyers working for Attorney General Jonathan Skrmetti of Tennessee, a conservative Republican, are handling the appeal. That office is often at odds with Funk’s; in late June, it called on the appellate court to deny Russell permission to appeal.

Russell is now back at Trousdale Turner Correctional Center, a notoriously rough private prison northeast of Nashville, where five men were stabbed in the course of three weeks earlier this year. Kaye has returned to her home in the mountains of East Tennessee, where she moved when Russell was incarcerated nearby, before his transfer to Trousdale. She lives alone, her brief time with her son preserved in photos that stand alongside her collection of framed family portraits. Her, beaming, with Alex in her arms; him, wearing tiny overalls, his gaze unfocused.

Eaton’s powerlessness, as an assistant DA, to rectify what she sees as a wrongful conviction felt more crushing than any failure, as a public defender, to prevent a client from facing an unjust punishment. “The weight is heavier because we did this,” she says. She wakes up in the night thinking about the Mazes — of how Kaye stepped out one afternoon to buy baby formula and returned home to find her life irrevocably broken. Of how Russell, as of this June, has endured 25 years of imprisonment. Of how the Mazes lost their son and then each other. And she agonizes over whether her decision to take on the case caused them harm. “We gave them a whole fresh set of trauma, and I’m haunted by that,” she says. “Before we got involved, I imagine Russell was trying to make peace with his situation and live the best life he could behind bars. He and Kaye had their visits together. And then we came along and disrupted all that. Teams of lawyers! Doctors! The elected DA! More than losing, what is weighing on me is that we gave them hope.”