Ohio lawmakers this fall will consider adding consumer protections to “clean energy” lending programs, responding to concerns they can burden vulnerable homeowners.

In testimony during state House committee hearings this year, some proponents of the bill pointed to reporting by ProPublica as evidence that Ohio should closely regulate the lending. That reporting showed that Property Assessed Clean Energy, or PACE, loans often left low-income borrowers in Missouri at risk of losing their homes.

Two Republican state House members from eastern Ohio are pursuing rules for PACE, though such a lending program has only been offered through a pilot program in Toledo. But lawmakers Bill Roemer, from Richfield, and Al Cutrona, from Canfield, said they want to make sure that, if companies try to bring a statewide program to Ohio, they comply with stricter rules.

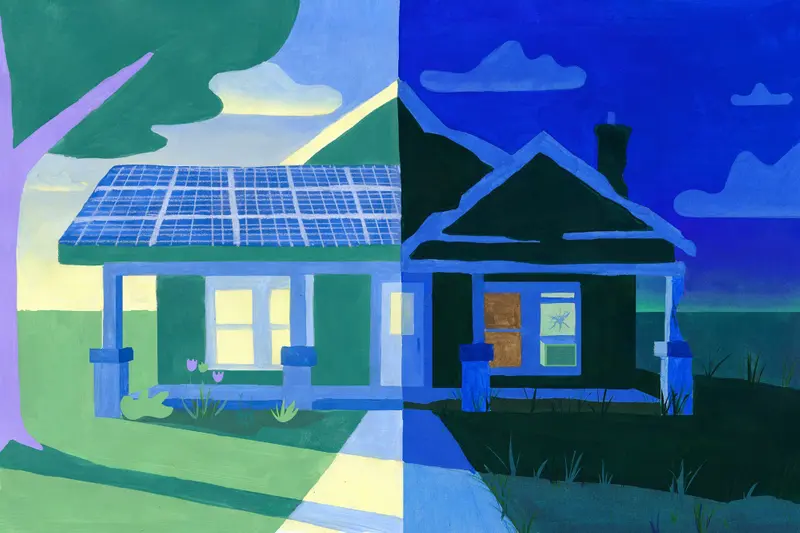

PACE offers financing for energy-saving home improvements that borrowers pay back in their property taxes. Unlike with some other types of financing, defaulting on a PACE loan can result in a home being sold in a tax sale.

Missouri, California and Florida are the only states with active statewide residential PACE programs. Ohio last year came close to becoming the fourth, after California-based Ygrene Energy Fund announced it would offer loans to homeowners in partnership with the Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority.

But the program never got started. Ygrene has since suspended all lending nationwide and last week agreed to settle a complaint by the federal government and the state of California that the company had harmed consumers through deceptive practices.

Roemer said in an interview that he co-sponsored the measure after talking to a coalition that included mortgage lenders, real estate agents and advocates for affordable housing and the homeless.

“You never really see all those people come together on a bill,” he said. “I did my research, and I said, ‘This is really a bad program that takes advantage of the most vulnerable people.’”

The legislative session ends on Dec. 31, leaving little time to pass the bill.

“It’s going to be a lot of work,” Roemer said, “but I think it’s very important that we do it.”

Ben Holbrook, an aide to Cutrona, said that after Ygrene’s withdrawal, the bill is “less of a reactive piece of legislation and more proactive.”

ProPublica found that state and local officials in Missouri exercised little oversight over the two entities that have run the clean-energy loan programs in that state. Ygrene and the Missouri Clean Energy District charged high interest rates and fees over terms as long as 20 years, collecting loan payments through tax bills and enforcing debts by placing liens on property — all of which left some borrowers vulnerable to losing their homes if they defaulted.

Reporters analyzed about 2,700 loans recorded in the five counties with Missouri’s most active PACE programs. They found that borrowers, particularly in predominantly Black neighborhoods, sometimes were paying more in interest and fees than their homes were worth.

PACE lenders said that their programs provided much-needed financing for home upgrades, particularly in predominantly Black neighborhoods where traditional lenders typically don’t do much business. They said their interest rates were lower than payday lenders and some credit cards.

Weeks after ProPublica’s investigation, the Missouri legislature passed and Gov. Mike Parson signed a law mandating more consumer protections and oversight of PACE. In Ohio, following our reporting, leaders in the state’s two most populous cities, Columbus and Cleveland, said they would not participate in any residential PACE plan.

Ohio’s bill would cap the annual interest rate on PACE loans at 8% and prohibit lenders from charging interest on fees. Lenders must verify that a borrower can repay a loan by confirming that the borrowers’ monthly debt does not exceed 43% of their monthly income and that they have sufficient income to meet basic living expenses.

The measure would also change how PACE lenders secure their loans. In states where PACE has thrived in residential markets, PACE liens are paid first if a home goes into foreclosure. And a homeowner can borrow without the consent of the bank holding the mortgage. Ohio’s bill would pay off PACE liens after the mortgage and any other liens on the property. In addition, the mortgage lender would have to agree to adding a PACE loan.

Ygrene officials did not respond to requests for comment. But a company official told the legislative committee that the bill would “unequivocally kill residential PACE.” Crystal Crawford, then a Ygrene vice president, told the committee in May that the bill was “not a consumer protection bill — it is a bank protection bill.”

Ohio’s limited experience with PACE illustrated how the program, with sufficient oversight, could be a low-cost option for borrowers. The Toledo-Lucas County Port Authority operated a pilot program allowing residents to borrow money for energy-saving projects without paying high interest or fees. A local nonprofit, the Lucas County Land Bank, made sure borrowers had the means to repay the loans, matched homeowners with contractors and made sure home improvements were completed correctly before releasing the loans.

Ygrene announced in August it had suspended making residential PACE loans in Missouri and California but was continuing to make residential PACE loans in Florida and commercial PACE loans in more than two dozen states. Commercial loans have not attracted as much attention from regulators because they tend to involve borrowers with more experience and access to capital who aren’t as likely as residential borrowers to default.

More recently, Ygrene’s website suggests that instead of making loans directly, Ygrene now operates as an online lending marketplace where consumers seeking personal loans for home improvements can enter personal information and receive offers from third-party lenders.

The complaint by the Federal Trade Commission and the California Department of Justice alleges the company deceived consumers about the potential financial impact of its financing and recorded liens on borrowers’ homes without their consent. To resolve the case, Ygrene agreed to provide monetary relief to some borrowers, end allegedly deceptive practices and meaningfully oversee the contractors who act as its sales force. The settlement must be approved by a judge.

Ygrene said in an email that the complaints date back to the “earliest days” of the company’s marketing of PACE loans in 2015 and that it had since taken “considerable action” to safeguard consumers.

“We deeply regret any negative consequences any customer may have experienced, as even one unhappy customer is too much,” the company said.