Hours after a burglary at a designer jeans store in St. Louis’ upscale Central West End neighborhood, at least 16 city police officers received an email alert with surveillance photos of the car believed to belong to the suspects — and an offer of a reward of at least $1,000 for any officer able to locate it.

The email was not from the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department, the police force that employs them and that residents fund with their taxes. Instead, it was from a retired city police detective named Charles “Rob” Betts, who also employs them at his private company, The City’s Finest.

The City’s Finest is no mere security firm. With about 200 officers moonlighting for it, it’s the biggest of several private policing companies that some of St. Louis’ wealthier and predominantly white neighborhoods have hired to patrol public spaces and protect their homes and businesses.

These neighborhoods buy patrols from Betts’ firm and other private police companies because, they say, they do not get enough from a city police department that struggles to provide basic services.

Under department rules, officers have the same authority when working for these companies that they have while on duty, one reason their services are in such demand. They can investigate crimes, stop pedestrians or vehicles and make arrests. And the police department requires that they wear their police uniforms when they’re working in law enforcement or security in the city, creating confusion about who they’re working for.

The result is two unequal levels of policing for St. Louis residents and businesses. Low-income and minority residents do not have the resources to hire police through a private company, and the department has struggled to provide patrols in parts of the city that suffer high rates of violent crime.

Meanwhile, the more affluent neighborhoods, which are less affected by violent crime, have raised millions of dollars to pay companies like The City’s Finest for granular attention from the same officers the police department has said it doesn’t have enough of. Officials in some of those areas praise The City’s Finest. They credit it with suppressing crime and helping merchants stay in business.

Dwinderlin Evans, a city alderwoman who represents some of the areas of St. Louis with the highest crime rates, including the neighborhoods of The Ville and Greater Ville, said the private policing system is unfair, “especially when you have neighborhoods that can’t afford to pay for extra policing.”

What’s more, The City’s Finest has raised its pay to exceed the department’s overtime rate — in essence outbidding the police department for its own workforce. Betts, in fact, has been clear that his company has to pay more to attract city police officers who might otherwise opt to work overtime.

Following questions from ProPublica, St. Louis Department of Public Safety Deputy Director Heather Taylor said the city planned a “complete review” of how off-duty officers are used and will hire a firm to “review for best practices that are going to be equitable to officers, the community and the city.”

Taylor acknowledged that, while working as a St. Louis police officer before retiring in 2020, she received an email offering a reward from The City’s Finest to work on a case. She said rewards for off-duty officers are “a practice we’re reviewing, that’s for sure.” ProPublica has identified four cases where The City’s Finest offered rewards.

Taylor said the bigger problem was low pay that makes secondary employment necessary. City police officers make a starting salary of $50,615, about 9% less than in neighboring St. Louis County and 13% less than in suburban Chesterfield.

Meanwhile, St. Louis Comptroller Darlene Green proposed boosting officer pay and benefits and bolstering community policing through a program called “Cops on the Block.”

St. Louis is far from the only U.S. city where neighborhood groups have hired off-duty officers. In Minneapolis, Atlanta, Kansas City and Dallas, neighborhood groups contract directly with local police departments or with the officers themselves. But in those cities, such patrols are typically managed by city officials and officers are accountable to department supervisors.

In other cities, such as Chicago, officers may work off-duty patrolling neighborhoods for private security companies, but they generally do not wear their police uniforms or represent themselves as police officers. The growing presence of off-duty officers in upscale Chicago neighborhoods has drawn concern from Mayor Lori Lightfoot, who said she didn’t want “a circumstance where public safety is only available to the wealthy.”

She added, “That’s a terrible dynamic.”

Experts in policing said they had never seen a system like the one in St. Louis. That system is “an extreme example of a pattern that can be found all across the country,” said David Sklansky, a professor of criminal law and procedure at Stanford University. “Public policing, for all its problems — and it has many, many problems — does represent a commitment to protect people equally, not based on their wealth or political power,” he said. “So the privatization of policing represents a retreat from that promise.”

Even some officials in well-to-do neighborhoods acknowledge disparities the arrangement creates. “It’s kind of a screwed-up system,” said Luke Reynolds, chair of the special business district in the city’s Soulard neighborhood, known for hosting one of the nation’s biggest Mardi Gras celebrations.

Reynolds said that it was unfair that Soulard has “affluence compared to a lot of other neighborhoods and gets extra patrols. It’s kind of screwed up that the police department can’t do their job and doesn’t have enough people, yet they can staff secondary patrols.”

Mayor Tishaura O. Jones, interim Public Safety Director Dan Isom and interim Police Chief Michael Sack declined interview requests.

Public servants, including police officers, are generally prohibited from accepting gratuities or rewards. It is a felony in Missouri to offer a benefit to a public servant for any specific action they take in that role. The St. Louis police manual says officers cannot accept gratuities, rewards or compensation — unless they are for work outside the department.

While Missouri law does not address whether it is legal for an off-duty police officer to accept payments, courts in other states, including Oklahoma and Connecticut, have held that an off-duty officer accepting rewards or gratuities from private individuals for their actions within the jurisdiction that employs them runs contrary to public policy. In 1899, the U.S. Supreme Court held that it was against public policy for federal marshals to receive a private reward for capturing a fugitive, comparing it to extortion.

Seth Stoughton, a former police officer who is a professor at the University of South Carolina law school and has studied police moonlighting, called emails from The City’s Finest offering private bounties “wild.”

“Officers used to get rewards like this,” he said, “but we’re talking 100 years ago.”

Betts said in an interview that he considers the practice “aboveboard” and not unlike an officer being recognized for good police work at a luncheon. He also compared it to Crime Stoppers, the anonymous crime tip lines that provide rewards for information — although police in Crime Stoppers’ St. Louis region cannot receive rewards.

“It’s merely just an incentive, to just pay a little more attention to this for a little bit. Everybody’s got their plates full,” Betts said. “Our job as police officers is to solve crime and there’s a lot of stuff that gets lost in the shuffle.”

He added: “Everybody works better when you incentivize them.”

St. Louis perennially has one of the nation’s highest rates of violent offenses among big cities, and, like most American cities, it has struggled to rein in crime. As a result, the performance of the police department is a point of almost constant conflict among city leaders. Some companies have even threatened to relocate because of crime.

The crime and violence, however, don’t occur evenly across the city. They are concentrated in the neighborhoods north of Delmar Boulevard, St. Louis’ well-known racial and socioeconomic dividing line. To the north of Delmar, nearly all of the residents are Black; more than half of residents south of Delmar are white. Home values south of Delmar are roughly seven times higher than those to the north, according to the city assessor.

Pockets of the north suffer from especially high rates of violent crime. In the city’s Sixth District, which contains about 35,000 residents in about 14 square miles, at least 76 murders were committed in 2020. That’s nearly as many as in the entire city of Minneapolis, a city of 430,000, and more than in Boston, with a population of 675,000, or Seattle, with a population of 735,000.

That same year, the Second District on the far south side of St. Louis, which has about 74,000 residents in 15 square miles, had just seven murders.

“It’s a crisis that we’re dealing with,” said Paul Simon, who owns a pet salon on the city’s north side. “Not only in the homes of the people that are in our community but the neighborhoods as well. We’re just in a desolate area. I can’t blame the police, because we have officers who are young and vibrant that are wanting to serve and protect, but the resources at the top” are not getting to struggling communities.

John Hayden, who served as chief from late 2017 until his retirement in June, said in public meetings that the department did not prioritize high-crime areas with its patrol plan. Instead, it deployed about the same number of officers to each of its six police districts. Those districts were drawn in 2014 to handle roughly equal volumes of calls for service — but without regard to the seriousness of the crimes.

Critics of the strategy said minor crimes are so pervasive in high-crime areas that victims typically do not bother to report them.

“If we prioritize them by violence, then some of you would have less officers in your districts, and some of you would have more,” Hayden told the aldermanic public safety committee in a videoconference in September 2020. “I think I would get a lot of resistance from some of the people that are on this call.”

Hayden said that day that he had tried to bridge the gap by supplementing patrols in the most violent areas with officers from specialized units. And he said that if he had more officers at his disposal, he would send them to areas with the highest violent crime rates, which “may not be something that everybody supports.”

The aldermanic committee advanced a measure that would have redrawn all six police districts and added a seventh to direct more officers to high-crime areas.

But Hayden told aldermen it was “not feasible” because the department would be spread too thin.

Hayden said in an interview that the ability of some neighborhoods to hire extra police while others cannot was simply “a matter of fact.”

Department leaders and the union that represents rank-and-file officers have for years portrayed the department as shorthanded, struggling to recruit and retain officers. Between 2015 and 2021, the department ran about 100 to 200 officers short of its authorized force of 1,340 officers.

Last year, Mayor Jones cut more than 100 unfilled positions. The department today has 1,053 officers, according to the Missouri Department of Public Safety. Even with job cuts, the force remains one of the largest in the nation per capita.

A longstanding complaint from neighborhood leaders is that officers are so busy responding to emergency calls that they seldom have time to engage with residents, build relationships in the community and act as a deterrent — to just be seen on the street.

Last October, about a dozen business owners in an area of the north side that includes the high-crime neighborhoods of Walnut Park East and Walnut Park West met at a restaurant with two St. Louis police officers. They expressed their frustration about the scarcity of patrols in their district. A reporter observed the meeting.

“We don’t even call you every time,” Tahany Jabbar, the chief operating officer of a chain of gas stations, told Sgt. Christopher Rumpsa and Lt. David Grove.

Rumpsa nodded and finished Jabbar’s thought: “You’d be calling all day.”

“To be honest, you guys don’t come,” Jabbar said. “No offense, but if someone’s not dying, you’re not coming.”

Rumpsa told Jabbar that when the city restructured its police districts in 2014, the Sixth District was meant to have 16 cars on the street at all times, but currently had far fewer.

“Patrol always has the least amount of resources,” Rumpsa said. “That’s the one thing they have got to change.”

ProPublica sought to observe The City’s Finest at work, after Betts suggested that a reporter ride along with some of his employees. The police department, however, blocked the request.

The department also blocked ProPublica’s access to data that would provide a picture of how the department deploys its officers. It declined to provide in-depth data on the activities of its patrol officers, which could have shown possible differences in how they respond in different neighborhoods.

But two groups of consultants did get access to that kind of information. Both concluded that the department does not put enough officers in high-crime neighborhoods.

Teneo Risk, led by Charles Ramsey, who has headed police forces in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., studied St. Louis’ police department in 2020 at the request of the area’s biggest publicly traded company, Centene. Teneo found the department lacked a comprehensive plan to address crime that left it “constantly in ‘fire-fighting’ mode,” leading to “persistent rates of crime and disorder.”

Its report said that in high-crime areas the department “finds itself chronically reactive to incoming calls for service, struggling to maintain sufficient numbers of officers on patrol, and lacking the resources to implement more community-based policing.”

Another group, Center for Policing Equity, studied the police department last year and found that while the department had “exceptional” response times to emergencies, officers in high-crime areas had little time for what is called proactive police work: deterring criminal activity with a visible police presence.

In two districts that lie mostly north of Delmar, the Center for Policing Equity found, officers were so backed up with calls they had little time for “a more comprehensive community-centered policing presence.” But in some areas with lower violent crime rates, the group said, the department was comparatively overstaffed.

Taylor, who retired from the police department as a sergeant in September 2020 and was hired as deputy public safety director after Jones became mayor in April 2021, said “a lot of things that we’re doing have changed” under Jones. She said the department has, in fact, sent more officers to work in areas struggling with high rates of violent crime.

Jay Schroeder, the president of the St. Louis Police Officers Association, the police union, said some officers feel the department has too many officers working in administrative roles. As the department has lost officers, he said, it has left more vacant positions in the patrol division, creating even more demand for private policing.

“The patrol division should be the division that has the most people and the most resources going to it, and it doesn’t seem like it’s been the focus over the last nine to 10 years,” Schroeder said. “As crime goes up, aldermen want policemen in their neighborhoods and the only way it seems they can get it is to pay” private policing companies.

“They’re paying to have policemen in their neighborhoods. That’s what we’ve come to.”

The sign over The City’s Finest’s headquarters off a busy St. Louis street in the city’s central corridor features a single word: POLICE. Many of its vehicles also feature the word POLICE and a logo that incorporates the St. Louis police badge. Other vehicles say SECURITY.

When there has been confusion among residents over whether the officers driving these cars are working on behalf of the city’s police department or a private company, The City’s Finest has tried to avoid drawing a distinction between the two. Speaking about his company, Betts once said it was “essentially an extension of the police department.”

It took decades for this mindset to become commonplace in St. Louis. Some city and neighborhood leaders have concluded private policing is the only way to get policing.

Betts said in an interview that private policing “allows an officer to focus in one particular area for the entirety of their shift, which puts a consistent police presence in that neighborhood.” He added: “We kind of look at ourselves as a force multiplier to the police department, and it’s at no expense to the city.”

Betts has even talked about rolling out a system to allow residents in the neighborhoods The City’s Finest patrols to bypass the city’s 911 system to contact a company officer to report an incident or request an escort. His company would then locate the nearest officer, using a GPS app on the officers’ phones, and direct them to handle the call.

The city, according to financial statements and other records, has at least 15 districts that levy taxes to pay more than $2 million a year for private police patrols, which include most of the city’s central corridor and several prosperous residential areas on the south side. And more are signing on. The Holly Hills neighborhood, which has one of the lowest rates of violent crime in the city, voted in August to create yet another taxing district, which would raise about $400,000 a year from a property tax surcharge and spend 30% of that for private police.

Steve Butz, a Democratic state representative who helped organize the Holly Hills ballot initiative, said he and his neighbors believe the city is “becoming ungovernable.”

“Is it fair?” Butz asked. “Is it fair that wealthier people drive nicer cars, have better homes, have home security systems, get better health care, go to better schools? People with less resources get the lower end of the stick.”

Private policing in St. Louis dates to the early 1990s and the theft of a Bob Marley box set from West End Wax, an independent record store in the Central West End. Tony Renner, who was then an employee of the store, recalled chasing the shoplifter down Euclid Avenue as the store’s owner, Pat Tentschert, fired shots at the thief.

Central West End resident Jim Dwyer said that Tentschert showed up at a neighborhood meeting one day soon afterwards, pounded her fist on a table and said that more needed to be done to make the neighborhood safe. (Tentschert died in 2017.) He said an alderman “whispered in my ear afterwards” that the neighborhood could form a special business district. “And we did.”

Residents from the area voted to form the Central West End North Special Business District in 1992. Their goal: improving neighborhood safety, including by hiring their own private police officers.

“There are people who are envious of the presumed wealth and privilege of our neighborhood in particular,” said Dwyer, who now serves as the district’s chair. But, he said, “we’re not abusing anything.”

Around the same time, Adam Strauss, whose father, Leon Strauss, had redeveloped thousands of homes in the DeBaliviere Place neighborhood next to the Central West End, founded Hi-Tech Security. The company dominated private policing until 2009, when the St. Louis Police Board stripped Adam Strauss of his city security license for engaging in an improper chase and using unnecessary force to arrest two people who had been suspected of trespassing on a gated Central West End street. Adam Strauss declined to comment.

Then-Police Chief Isom told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 2009 he wanted the department to “have better control over where those services are and where those people are.” He added: “The idea would be there would be no middle person. So you would not have any private security company in the middle.”

But that never happened. Instead, private policing continued to grow. A new company — this one run by police officers — was starting to compete with Hi-Tech for neighborhood policing contracts. In 2007, Betts was a beat cop working in the Forest Park Southeast neighborhood near the Washington University medical campus. The university’s redevelopment arm was investing heavily to stabilize the surrounding area.

Some neighborhood leaders viewed the neighborhood’s stubborn crime and the presence of gangs as an obstacle to progress. According to Betts, Brooks Goedeker, who was then a community development specialist with the medical center, suggested that he add bike patrols conducted by St. Louis police officers. Goedeker did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

Although Betts’ online resume says he has owned the company since July 2007, when he was still on the force, he has said over the years that his mother owned the company. Since at least 2006, the police department has prohibited members of the force from having a financial interest in or acting as officers or directors of a private security company. Betts said he had to form his company “in a certain way to ensure that things weren’t being violated.”

Betts retired as a homicide detective in 2013 after being injured in a traffic accident on duty.

Charles P. Nemeth, author of the book “Private Security and the Law” and the retired director of the Center of Private Security and Safety at John Jay College in New York, said rules regulating officers owning security companies are important because “private security firms may deal with a criminal case or other matter in a distinctively different way than public policing may be required to handle.”

Nemeth, now the director of the Center for Criminal Justice Law and Ethics at Franciscan University of Steubenville in Ohio, said officers in uniform working for private companies is “very troublesome” because it blurs the basis of their authority. “This is a new one to me, and I’ve been watching this a long time,” he said.

Indeed, nothing suggested that an officer patrolling a Central West End sidewalk on a recent evening was moonlighting for a private company. Lt. JD McCloskey, who works as an aide to the St. Louis police chief, acknowledged to a reporter that he was working for The City’s Finest, though he was wearing his police uniform. He said his responsibilities that evening were to maintain a visible presence along a stretch with several businesses and “interact with citizens and businesses.”

The private policing system puts law enforcement in the hands of interests that are not part of the city’s government and, as a result, are not accountable to taxpayers citywide.

The police department’s only oversight of private policing is screening employers of off-duty officers and auditing whether the officers work more than the maximum hours allowed: 32 hours a week total, or 16 hours a day including their eight-hour department shift. A state audit two years ago found the department didn’t adequately track moonlighting; since then, police have assigned officers to monitor the practice.

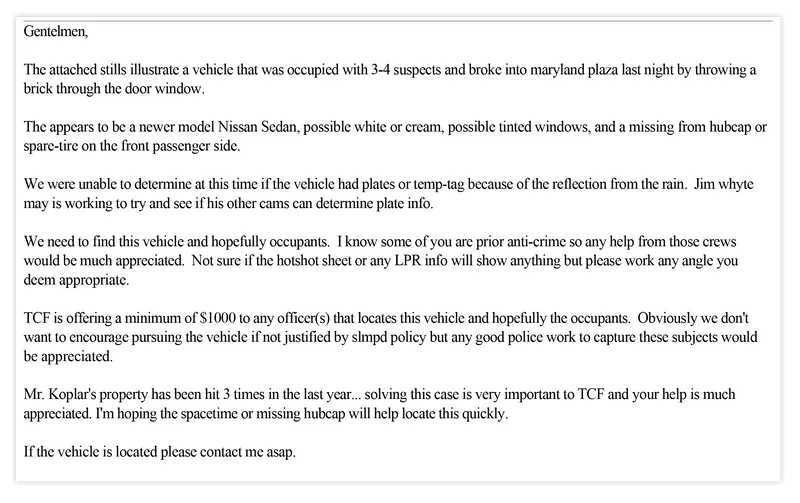

Officers on patrol for private police companies don’t necessarily go where crime is happening; they go where they’re paid to go. So it was that a burglary in the Central West End prompted a substantial reward offer from The City’s Finest and a search by several officers across St. Louis for the potential suspects.

The landlord of the burglarized jeans store was no ordinary resident. He was Sam Koplar, a prominent local developer. In addition to Koplar being a board member of one of the Central West End taxing districts that had hired The City’s Finest, his company separately hires officers from The City’s Finest to protect his properties in the Central West End.

Betts wrote in the email to officers that Koplar’s properties had been targeted by criminals three times in the previous year. He implored officers to “work any angle you deem appropriate” and even recruit fellow officers from an undercover task force to help find the car.

“Solving this case is very important to TCF and your help is much appreciated,” he wrote, using The City’s Finest’s initials. The email was sent to some of the officers’ department email addresses; among the recipients were two of the six St. Louis police district captains at that time.

One of those captains, Michael Deeba, who also worked for The City’s Finest at that time, responded from his department email with a key detail: the plate of the wanted car. Another officer emailed the group from his email address at The City’s Finest that a license plate reading camera had detected the car on a street several miles away. A short time later, a suspect was taken into custody at an address near where the car had been seen, although it’s not clear if anyone was prosecuted for the break-in. It was also not clear if any officer was given the reward money.

Deeba, who was charged in April with stealing for allegedly moonlighting for another company on police department time, said that “the whole department,” including its last three chiefs, knew of the rewards. But he said neither he “nor my people would take such a reward.” He has pleaded not guilty to the stealing charge. Deeba has said the department placed him on forced leave; the Missouri Department of Public Safety said he was no longer employed by the city.

Koplar said in an interview that he doesn’t like paying for additional policing, saying the police department should provide adequate patrols. “But unfortunately,” he said, “the police department is stretched very thin.” He said the repeated break-ins at his property were frustrating. “We were exasperated. Our job as the property owner is to provide a safe environment.”

Betts said in an interview that offering a reward was warranted because it brought attention to a crime that the police department might not have devoted the resources to solve. “That business, that area, was a very important part of the business district of the Central West End,” he said. “It was hit three times, which ultimately cost the Koplar family to lose their client, which was detrimental to their business. And nothing was being done.”

Betts said he does not know how often he offered rewards: “It wasn’t like I was doing that every day. It’s usually for a high-profile crime or something that’s of great importance to our efforts.”

ProPublica discovered the rewards by obtaining emails between the company and some members of the department through an open records request. Only emails copied to police department email accounts were subject to the records request.

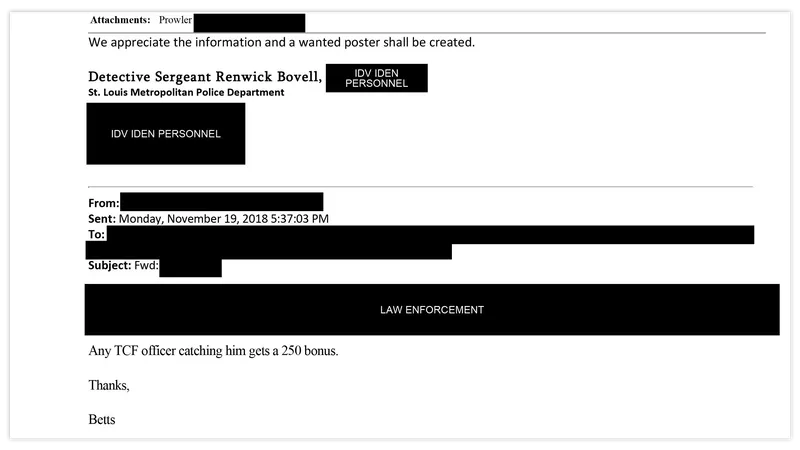

In another case, after Betts emailed a group of city officers to offer $250 for the arrest of a suspected prowler, a detective sergeant for the department responded on his department email that a “wanted poster shall be created” for the suspect. The detective sergeant, Renwick Bovell, did not return requests for comment.

Mary Fox, director of the Missouri public defender system, said she had “real concerns with a private organization saying, ‘Hey, if you arrest this person, we’ll give you money,’ when there has not been a judicial determination that the person should be arrested. For a police officer to arrest someone without a warrant, they have to have reasonable suspicion that a crime occurred and this is the person who committed the crime. And it sounds like they are just taking the word of the organization that’s reaching out to them without any investigation by themselves or their department. That’s problematic.”

Nate Lindsey is a former official for a taxing district in Dutchtown, a south city neighborhood that struggles with crime. In 2018, Dutchtown neighborhood officials tried to hire The City's Finest but could not afford to. “Even if a poor neighborhood that lacks resources goes as far as to tax itself to attempt to bring better policing resources into the streets, it’s going to struggle if it doesn’t have enough money to compete with deeper-pocket interests,” he said.

For city residents, he said, “the expectation is that the police department is making decisions with the public good in mind as a whole and that process isn’t affected by special interests or the amount of money that can be provided to either individual officers or companies like The City’s Finest,” he added. “They’re not doing that now.”