When questioned by federal officials or faced with an accident, the nation’s powerful freight railroad companies say they are among the safest employers in America and tout their injury records to prove it.

But those statistics belie a troubling dynamic within the companies, ProPublica found: a culture that blames workers when they get hurt and motivates supervisors to go to extreme, and sometimes dangerous, lengths to keep injuries off the books.

The playbook is scattered across the pages of sworn court testimonies and complaints to workplace regulators. One supervisor said in a deposition that he drove a track repairman, who had been vomiting and stumbling from heat stroke, to a job briefing site an hour away instead of a hospital. Another admitted he paid a carman to hide his head injury. A third accompanied a hurt worker into an emergency room, according to a recent complaint to regulators, and demanded, successfully, that a doctor change his discharge record so that the railroad would not have to report the injury to the government.

Other railroad workers told ProPublica they had gotten hurt on the job but chose to keep it quiet, saying they were aware of what happened to those who talked.

The allegations of harassment and retaliation came alive in hundreds of interviews conducted by reporters and thousands of records they reviewed, including federal lawsuits stretching back 15 years, complaints to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration as recent as this summer and hours of audio recordings captured by workers.

The reporting showed how railroad officials pushed arguments that workers faked their accidents or were at fault for them, at times hiding evidence to the contrary. The officials then punished and fired workers, including those who lost fingers and limbs, for reasons that fell apart when tested in court.

Judges, juries and regulators found several of these firings unjust and illegal; documents of their official findings burned with outrage:

“Reprehensible.”

“A culture of retaliation.”

“Pattern and practice of willful misconduct.”

“There is no justice for employees injured on the job.”

Though the companies won at least 10 of the cases, every one of America’s six largest freight rail operators, the so-called Class 1s, settled lawsuits with workers who alleged they were retaliated against, harassed or fired after injuries; of 185 suits, at least 111 were resolved this way. Several more are ongoing, and at least a couple resulted in jury verdicts for the injured workers.

In addition, in the past five years, OSHA regulators found merit to at least six complaints alleging retaliation, and administrative law judges working for the Department of Labor sided with workers in at least six more cases within that time period. Regulators acknowledge these cases are likely an undercount, because not all workers will go through the arduous process of filing a complaint or lawsuit.

Several officials who investigate worker injuries told ProPublica that the rails are unique in how aggressively they deal with hurt workers. The antagonism is baked into railroad culture, ProPublica found.

In other industries, employees can draw workers’ compensation, no matter who is at fault for their injuries; in return, they are prevented from suing their companies. The railroads, however, are governed by the Federal Employers’ Liability Act, which allows hurt workers to sue and get bigger payouts but requires them to prove their company was at fault.

Layer on top of that company performance metrics and bonus systems that punish managers for reporting injuries. “We’re constantly going up against that, and it’s very frustrating,” said Michael Wissman, who audits railroad companies for the Federal Railroad Administration, which oversees rail safety. He said he recently set out to investigate an injury an employee’s colleague reported, but then, when he asked the worker about it, the man denied he was hurt enough to need government attention and seemed hesitant to say more.

“I feel for the employee if he was fearful for his job,” Wissman said. “My hands are kind of tied. I have nothing to go on.”

Congress has known for decades of the railroad industry’s propensity for hiding and lying about worker injuries. It held a landmark hearing in 2007 to examine the practice. Congressional staffers found government reports that identified “a long history” of railroads underreporting injuries, deaths and near misses. They had identified more than 200 cases in which workers said they were harassed following injuries and lined up a number of them to speak. “We are going to hear some very startling and dismaying testimony,” House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Chairman James Oberstar said at the beginning of the hearing, “but it has to be laid out in the public.”

In the wake of those hearings, Congress passed an update of the Federal Railroad Safety Act in 2008, which toughened safety rules, oversight and whistleblower protections and specified that railroad companies had to ensure their injured workers got prompt medical care.

But 15 years later, ProPublica found, many of the problems persist, in large part because many of their drivers persist. “I believe it’s linked to their bonus structure,” Wissman said of the rail companies. “There’s no ands, ifs or buts about it.”

The Association of American Railroads, the industry’s lobbying arm, did not comment on those incentives but said employee safety has improved because of the companies’ concerted efforts.

“Railroads patently reject the unsubstantiated allegation that there is a systemic safety culture lapse or widespread underreporting of injuries,” association officials said in a statement. “Isolated incidents or behaviors do not reflect an industry-wide problem or account for the thousands of professional railroaders who work safely and responsibly every day. Let us be clear: there is no distinction between railroad culture and safety culture. Railroad culture is safety culture.”

The railroad companies mentioned in this story echoed those points, saying their rules require them to promptly report injuries and forbid retaliation against hurt workers. “Allegations that managers are incentivized to hide or ignore injured employees are false,” a Union Pacific spokesperson said in a statement. Read the companies’ and AAR statements.

Karl Alexy, chief safety officer for the FRA, said there is a “yawning gap” between what he hears from top leaders and the management culture on the ground level. “These guys up at the headquarters certainly have the perspective that it’s unacceptable and they don’t want it to happen,” he said. In fact, according to the FRA, Union Pacific disciplined one or more managers this summer for misclassifying injuries so that they didn’t have to report them to regulators.

“But then they’ll turn around and put these unrealistic expectations on these managers out in the field,” Alexy said, “and [the managers] are like, ‘I got to do whatever I can do, because otherwise, I’m going to lose my job.’”

ProPublica previously reported about how, in a quest to maximize profits, railroad companies are pushing managers to keep trains moving at all costs by using performance metrics that penalize them for delays, even those caused by fixing safety hazards. Those scorecards, which can dictate five-figure bonuses, also tally worker injuries. But it’s not just about money.

ProPublica spoke with seven railroad workers who were managers at CSX, Norfolk Southern, Union Pacific and Canadian National between 2011 and 2021. Most are still employed by those companies. All described an industry philosophy that deems every injury preventable — and the fault of the employee and their manager.

Having a spate of injuries can kill a career, they all said. “It decides who is on the fast track for promotion … and it decides who fizzles out,” one manager said. Another said that when he was first promoted, he slammed his finger in a train door and broke it. “There was no way in hell I was going to report that to anybody,” he said. Today, his finger is still bent.

None of the former managers believed that employees should escape discipline for injuries due to sloppiness, poor oversight or failure to follow procedures. But they said the railroad’s prosecutorial approach to handling injuries includes those no one could have avoided.

As supervisors, they all said, the injuries they dreaded most were those serious enough to report to the FRA, because they invite time-consuming government intervention and ire from higher-ups who brag about their safety record to customers, shareholders and the public. Federal regulations require companies to report any injuries that result in a worker being prescribed certain medications, missing time from work or being assigned to light-duty work.

That context helps explain some of the behavior ProPublica discovered.

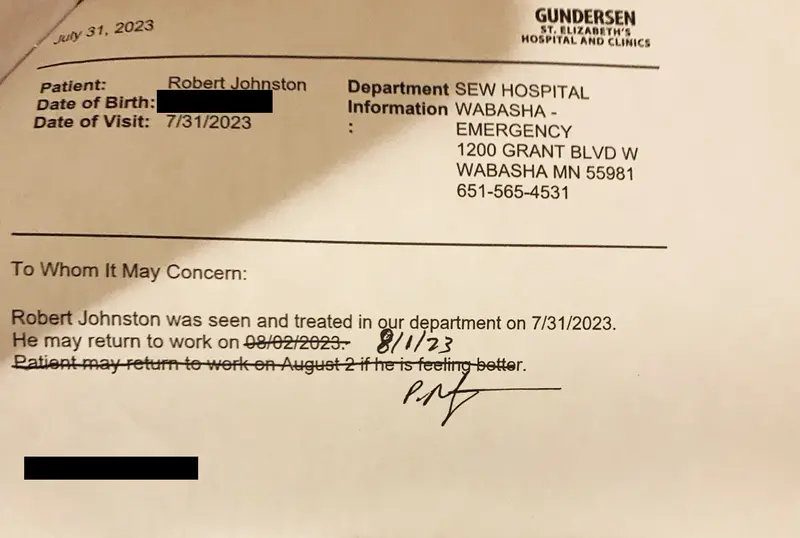

This August in Minnesota, Canadian Pacific Kansas City bridge specialist Robert Johnston smashed his knee after his leg fell between railroad ties. He said his manager called him repeatedly while he was getting an X-ray at the hospital. “He’s like, I will get you whatever you need, over the counter,” Johnston said. “Anything that you need if you don’t take prescription drugs.”

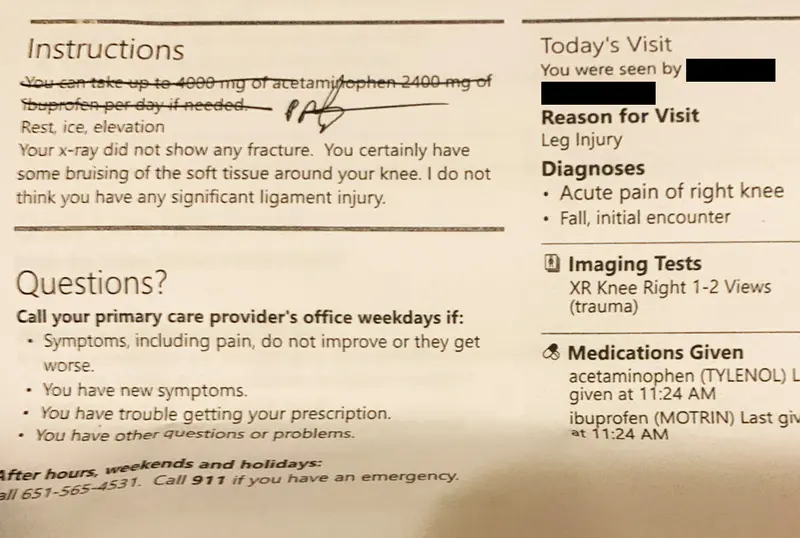

Johnston had no fractures but was still in pain, his knee swelled to double its normal size, so an emergency room doctor told him to take medicine and a day off from work. But when his bosses later read his discharge papers, they deemed them unacceptable, Johnston told ProPublica and said in a complaint he filed with OSHA.

In the complaint and interview, he said Nate Lund, one of his supervisors, told him they needed to go back to the emergency room and get the papers changed. Johnston said he refused, but Lund insisted. “We sat there and sat there and he hounded me and hounded me,” Johnston said. Desperate to go home, Johnston said, he relented. (When reached for comment, Lund hung up on a ProPublica reporter and later did not respond to questions sent by text.)

At the hospital in Wabasha, Johnston said Lund took over, telling medical staff he needed the paperwork to change. The doctor, Johnston recalled, was beside himself, shaking his head in disgust. “Fucking railroad,” he recalled the doctor saying, and then mouthing to him, “Get a lawyer.” Johnston recalled Lund asking the doctor if he could retype the discharge papers. The doctor refused; the most he would do is cross out the instructions in pen, leaving the original instructions plainly visible.

Despite the discomfort in his knee, Johnston said, he went to work the next day and his managers were happy to see him and very accommodating. “I mean, they literally would have given me a La-Z-Boy and fed me grapes,” he said. “They did not want me to do anything, but they didn’t want me to have a day off. It was really weird.”

Johnston resigned from the railroad about three weeks after his accident. In a statement, Canadian Pacific Kansas City said Johnston’s story “does not align with the information [the company] has regarding this situation” and declined to comment further. An OSHA investigation is pending.

An earlier case peels back the pressures managers face when their workers get injured.

In 2015, Pierre Hunter, a general supervisor at Illinois Central Railroad, a subsidiary of Canadian National, got a call from a higher-up after one of his employees, carman Cameron Davis, hit a pothole while driving an ATV in a Memphis rail yard and damaged it. Word had gotten around that Davis had gotten hurt in the accident.

Hunter’s supervisor Darrell Hoyt wanted Hunter to make sure the injury didn’t have to be reported, Hunter said in a recorded statement with Davis’ lawyers. “You need to get that fixed. Handle it. Do what you got to do,” Hunter said Hoyt advised him. “Don’t put your job on the line for another employee.”

Hunter said he was certain his job hung in the balance as he repeatedly called Davis and pressured him not to tell anyone he’d had doctors look at his head, which was throbbing and swollen. Davis recorded some of the calls, which later became part of a lawsuit against the company. “Just stick to your story if anybody asks. You never went to a damn hospital. You ain’t injure yourself at all,” Hunter said. “Don’t say shit else to … no goddamn body, not a fucking soul on CN property.”

“What’d the doctor say?” Hunter continued. “They give you something or they say you’ll be all right? … No medication, none of that shit, right?”

In the recorded call, he advised Davis to cover the big bump on his head with a knit hat so that he wouldn’t arouse talk among his co-workers.

Hunter later told Davis the best way out of trouble for the accident was to sign a statement admitting it was his fault, not tell anyone about his injury and take a 15-day suspension without pay. “Take my word, they want to get rid of you,” Hunter recalled telling Davis. Davis said he couldn’t afford to be off for two weeks, but Hunter had a way around that, too: “Bribe him to not report it,” he said in his statement to Davis’ lawyers. While Davis served out his suspension, Hunter gave him $1,500.

Davis ultimately reported the injury anyway. About six months later, he was fired, accused of violating safety rules like not maintaining the proper distance away from moving equipment and working without protective eyewear. "I was targeted because of what happened,” Davis told ProPublica. “It was retaliation for the injury.”

Once the railroad heard the taped phone call, it also fired Hunter.

Emails, calls and social media messages to Hunter went unanswered. Hoyt told ProPublica in a message that he didn’t remember the affair and that it wasn’t “consistent with company policy or my application of safety commitments.” Canadian National settled the case with Davis for an undisclosed amount. A spokesperson told ProPublica the railroad doesn’t comment on “individual personnel cases.”

During the 2007 hearings on Capitol Hill, workers testified about being left to die by the tracks while railroad managers ignored pleas for care. The 2008 update to the Federal Railroad Safety Act required the companies to provide “prompt medical attention” and mandated that railroads bring injured workers to the hospital as soon as they ask.

About five years after the harrowing congressional testimony, outside Chicago, a supervisor was driving a Union Pacific machine operator, Jared Whitt, to the hospital. Whitt’s lips felt as if they were about to burst and his arms and legs tingled, he testified as part of a lawsuit he later filed. He closed his eyes and thought about his five kids. Was he dying? “Please,” he recalled telling his manager: “Get me there. Please hurry.”

Whitt had suffered a heat stroke as June temperatures climbed to about 100 degrees, and his manager, work equipment supervisor Dave Birt, believed Whitt was going into cardiac arrest, Birt said in his deposition. They had just started toward the hospital when Birt’s cellphone rang. “Well,” Whitt heard Birt say, “what do you want me to do?” A pause. “I’m no doctor, but when a man’s arms are numb and tingling, I’d say he needs to go see one.” Pause. “I’m pulling over.”

Birt held the phone to Whitt’s ear. Whitt couldn’t hold it himself because his numb arms had retracted, his fists clenched at the top of his chest, Whitt said in his pretrial deposition. The man on the other end was Birt’s boss, manager of track programs Talmage Dalebout. “Why don’t we just bring you back here to the job site and get you cooled down,” Whitt recalled Dalebout saying. “If you get cooled down, you’ll probably be OK.” Birt declined to comment when reached by ProPublica. Dalebout didn’t respond to calls, texts and social media messages.

Union Pacific claims in the lawsuit that Whitt never requested to be taken to the hospital and, when Birt says he asked, Whitt chose the job site. But experts say workers suffering from heat stroke —a potentially life-threatening condition marked by confusion in which body temperatures can rise to 106 degrees — lack the faculties to make any decision for themselves; someone should always take them to the hospital regardless of what a worker requests. In hindsight, Birt said later in deposition, he wished they had continued to the hospital.

Back at the job site, Whitt testified that he remained in Birt’s truck for some time. A co-worker brought him Gatorade and bottles of water. Then he recalled ending up in a trailer, where people were pouring cold water over him and his co-workers were rubbing his arms to restore circulation, according to Whitt. He didn’t get to the hospital until some four and a half hours after his body started tingling and his consciousness began slipping, according to court records. His roommate drove him.

The heat stroke partially disabled Whitt, he said in his court deposition. He no longer had the strength to work at the railroad and for years struggled with his left arm and hand, which went numb whenever he raised it above his shoulders. Two years later, Whitt had surgery to restore movement to his left arm. The surgeon cut away part of his left pectoral muscle and removed his left upper rib. Whitt sued Union Pacific, and the railroad settled with him for an undisclosed sum.

Whitt, who now works as a home inspector, said he still can’t believe that a manager intervened to redirect him away from the hospital. “It’s unfathomable,” Whitt told ProPublica. “I can’t imagine treating a human that way.” Today, he says, his arm remains tight, with a limited range of motion and numb at the armpit.

The cautionary incident didn’t appear to influence what happened three years later, when another Union Pacific worker fell ill on a blistering hot day in Kansas, according to records from a lawsuit he later filed.

Guillermo Herrera worked in the same road crew as Whitt, which roves throughout the company’s western region repairing tracks. On July 26, 2015, Herrera’s worried co-workers called higher-ups. The track repairman had vomited and was out of it, according to the court records. When the bosses came to get Herrera, he needed assistance getting into a pickup truck. He whispered a plea for help into his foreman’s ear; “Ayudame,” he said, according to a court deposition.

Considering the shape he was in, Herrera’s co-workers assumed he was being taken to a hospital, they testified. And indeed, there was one 21 minutes away. But instead, track supervisor Charley Diaz drove him to a job site to cool down, according to his deposition. The job site was about an hour away.

Once again, Union Pacific defended its actions, saying that Herrera would have been taken to a hospital if he had asked, and that Herrera at one point said he wanted to go back to his motel room. (Herrera contends that he was in and out of consciousness but kept saying the word “hospital.”) Either way, Diaz himself suggested he was concerned about Herrera’s mental state. “I told him to stay awake,” Diaz testified. “I didn’t want him going to sleep or anything like that, so I just watched him and asked him how he was feeling mostly.” (Diaz did not respond to calls and text messages.)

Diaz drove Herrera to the job briefing site, a boxcar office on wheels. Safety captain Bobby Steely testified that he checked on Herrera in the truck several times, each time asking him if he wanted to go to a hospital. (Steely declined to comment when reached by ProPublica.) After about 20 minutes, he said, Herrera finally said yes.

Herrera was ultimately diagnosed with heat stroke, which profoundly altered his life.

In the year that followed, he later testified, he could no longer drive safely or get a decent night of sleep. His morning walk around the block was so difficult, he had to sit down for a half hour or so until the tingling in his legs dissipated. His days were all about rest and heat avoidance, and he did physical therapy six hours a week. His family barred him from the kitchen because his memory issues had caused him to start two small fires.

He sued Union Pacific in 2015, a case that settled for an undisclosed amount. Union Pacific did not comment on either of the cases, but a company spokesperson said in a statement that nothing is more important than safety. “Employees complete annual training on how to respond to and handle injuries,” the spokesperson said.

An injury can paint a target on a worker’s back, ProPublica found.

It happened to Montana conductor Zachary Wooten, who damaged his right wrist so severely in 2015 after falling from a BNSF train that he needed surgery. The culprit, he said, was a defective latch on the train; he struggled to open it and felt a stab of pain as his wrist popped. When he tried to climb back up onto the engine after inspecting the train, his wrist gave way and he fell to the ground.

From that moment forward, court and company records show, his supervisors and BNSF lawyers searched for ways he could have come to work already hurt. “They always tried to blame it on something else that happened at home and say you dragged it into work,” said Wooten’s union representative, retired switch foreman Mark Voelker.

According to records from an internal company hearing, a superintendent of operations had visited 27-year-old Wooten when he was in the emergency room and asked him how he got a scrape on his other arm. Wooten, who was on pain medication, told the manager he got the rug burn during sex a day before the injury — an episode that also involved his bed breaking. The company took that morsel of information and used it to insinuate that’s also how he damaged his hand, records show. “I am not comfortable answering questions about my sex life,” Wooten told railroad officials during the internal hearing.

ProPublica learned of other unusual arguments used to blame workers, and not safety hazards, for their injuries. Machinist Bobby Moran was wearing his company-issued safety gloves in 2019 when one got caught in a lathe, snapping bones from his forearm down and severing a finger; another damaged finger later had to be surgically amputated. Union Pacific fired him after accusing him of using the equipment in the Arkansas yard for personal reasons, perhaps to manufacture a firearm silencer. “I was fearful,” Moran said. “Me and my wife were thinking, ‘When is the FBI going to show up?’”

Moran said he had been creating a piece of equipment that would improve the functionality of a hydraulic pump he and his fellow machinists worked with in the repair shop; his legal team showed the railroad’s attorneys the device’s schematics and a video of it working just as he said it would. According to Moran’s lawyer, Union Pacific never provided evidence to support its weapon theory before it settled the case. Union Pacific did not comment on it.

As for Wooten, BNSF pulled several angles of videos to show how, in the hours before the accident, he appeared to be favoring his right wrist by using his left hand. What the company didn’t know is that, according to Wooten, he is ambidextrous, as adept with one hand as with the other. Two months after his accident, the company fired him, accusing him of lying about his injury. Then, when Voelker gave information to Wooten’s attorney about the unrepaired loose handle on the locomotive, he, too, was fired. His dismissal letter cited his “misconduct and failure to comply with instructions when you disclosed confidential BNSF business information.”

A jury believed Wooten’s story, finding he was wrongfully terminated in retaliation for his on-the-job injury; he was awarded $3.1 million. U.S. District Judge Dana L. Christensen denied the company’s appeal, calling BNSF officials’ testimony biased, unreliable, inconsistent and lacking in credibility. “They latched on to an early formed presumption that Wooten was being dishonest that jaded their treatment of Wooten throughout,” the judge said. The company settled with Voelker over his wrongful firing claim.

BNSF has lost at least three cases in recent years in which it tried to allege a worker faked or exaggerated their injuries. In one, the company fired a worker in 2020 who suffered neck and back injuries in a crash because a private investigator surveilled him exercising at the gym — part of a physical therapy and a workout regimen ordered by his doctor. OSHA described the behavior as a “knowing and callous” disregard for his rights and found merit to his argument that he was retaliated against for getting hurt. The company settled his case in court in May.

BNSF did not comment on any cases but said it prohibits retaliation against employees for reporting injuries or safety concerns. “We take any alleged violation of those policies very seriously,” the company said in a statement.

Former managers interviewed by ProPublica said their companies foster a culture in which every injury claim is treated with skepticism. The presumption, one said, is: “How is the person trying to [screw] me? How can we prove he’s lying?”

ProPublica obtained about 10 hours of recorded railroad manager phone meetings that give a window into how supervisors discuss injuries and their efforts to catch employees violating rules. They took place among Norfolk Southern managers in its Tennessee region between January and April of 2016 and were led by Division Superintendent Carl Wilson and Assistant Division Superintendent Shannon Mason. Wilson, whose LinkedIn page describes him as retired, did not respond to calls, text messages, social media messages and a letter sent to his home. Mason, who is still with the company, declined to comment. Norfolk Southern wouldn’t answer ProPublica’s questions about the calls, only saying that they were “routine and focus on safety.”

While the meetings were indeed largely devoted to business like company performance, productivity and safety, the tenor changed nearly every time an injury was brought up, as Wilson and the other supervisors expressed incredulity that it was legitimate and discussed ways the injury could be proven to have been the employee’s fault.

In one call, they discussed an employee who also owned a motorcycle repossession business and questioned whether the injury could have happened there. Wilson told the managers he asked for surveillance of the engineer. “Hopefully he messes up,” Wilson can be heard saying in the call.

On another call, Wilson described one 67-year-old employee with a shoulder injury as a “piece of work” and insisted he was trying to get out of a training session. The managers cast doubt on another employee who said he was attacked by bees: “If there was anything, it looked more like a shaving bump.” Wilson, in another call, lamented losing the chance to fire an employee before he injured himself by slipping and hitting his head: “Quite honestly, he got us before we could get him.” And when they brought up a female conductor who felt her knee pop when she stepped onto a train, the conversation turned to her weight.

“She’s a big gal,” said Wilson, who also referred to her as “cheerful.” “Her joints, her knees are gonna wear out eventually sooner than most of us simply because we don’t carry the amount of weight that she carries.” He joked that if another manager had run her out of the company earlier, they “wouldn’t have this problem.”

The comments disgusted the worker, Amy Simmons, who called the discussion “embarrassing” and “unprofessional” when ProPublica shared the recording with her. She said that railroaders’ knees wear out because they are asked to walk mile after mile along rocky ballast and the company has cut staffing to the bone, demanding moreand more from each employee. “They’re wearing us out because they won’t give help,” she said. “It’s not my weight. If anything, it’s the fact that they overwork us.”

She has since left the industry and said she regretted the amount of time she wasted and all that she sacrificed trying to be a good employee. To her, the calls illuminate the way railroad companies truly see their workers.

“They hire you to fire you,” she said. “They don’t care.”

Jeff Kao, Carolyn Edds, Mollie Simon, Mariam Elba, Miriam Pensack and Ruth Baron contributed research.