Three Democratic U.S. representatives introduced a bill last week that would require the Environmental Protection Agency to create a pilot program for air monitoring in communities overburdened with pollution. The program would have a $100 million annual budget over five years to allow local agencies to monitor the air quality in neighborhoods, block by block.

One of the lead sponsors, Rep. Kathy Castor, D-Fla., cited ProPublica’s work on toxic air pollution as a factor motivating her introduction of the Environmental Justice Air Quality Monitoring Act. “I’m grateful for ProPublica’s work to expose the devastating consequences of air pollution, economic inequality, and environmental racism on vulnerable Americans,” Castor said in an emailed statement to ProPublica, after highlighting stories from our “Sacrifice Zones” and “Black Snow” series on social media.

“The data provided by ProPublica’s air pollution mapping tool and the Environmental Protection Agency demonstrates the urgent need to decisively address toxic air pollution that is putting Americans at greater risk for cancer and other harmful health outcomes,” Rep. A. Donald McEachin, D-Va., a co-sponsor of the bill, wrote in an email. “For too long, low-income communities and communities of color have borne the brunt of environmental degradation and injustice, and it must end.”

Sen. Ed Markey, D-Mass., introduced a nearly identical bill last July, weeks after ProPublica and The Palm Beach Post published an investigation into air quality in the Florida Glades, one of the country’s largest cane-sugar-producing regions. For years, residents in the area’s largely Black and Hispanic communities had been saying that the sugar industry pollutes the air when, as part of the harvest, workers set fire to the crops to rid the cane of its outer stalk. Sugar companies have long insisted the air was safe to breathe.

State officials used a single monitor to track air quality across the entire 400,000-acre sugar-growing region. So the news organizations worked with residents to set up commercially available air sensors that measured particulate matter during the burn season and identified short-term spikes in pollution on days when the state had authorized cane burns and when smoke was projected to blow toward the sensors. These shorter-term spikes in pollution, which are a defining feature of Florida’s harvesting process, had been obscured by federal and local regulators’ reliance on longer-term averages. The spikes often reached four times the average pollution levels in the area — high enough that experts said they posed health risks.

In November, ProPublica began publishing “Sacrifice Zones,” a series of stories that exposed how and where toxic air pollution elevates the cancer risk of residents who live close to industrial facilities. An estimated 256,000 people live in areas where the cancer risk exceeds levels the EPA considers acceptable, ProPublica found through a first-of-its-kind analysis. Predominantly Black census tracts have more than double the estimated cancer risk of majority-white tracts.

Our analysis used EPA air modeling to reveal the estimated industrial cancer risks at a granular level in every neighborhood across the country. Such models are a starting point for identifying areas in need of actual monitoring. The new bill proposes a hyperlocal approach by requesting “ongoing measurements of air pollutants at a block-level resolution.”

A spokesperson for Rep. Ritchie Torres, D-N.Y., another lead sponsor of the bill, said in an email that ProPublica’s stories “helped raise attention on this issue as well as concerns from our constituents. Our congressional district, NY-15 based in the South Bronx, has one of the highest levels of pollution in the entire state of NY. Residents are deeply impacted by bad air quality that leads to dangerous health conditions.”

If passed as currently written, the Environmental Justice Air Quality Monitoring Act would award grants or contracts to state, local and tribal agencies in partnership with local nonprofit groups or organizations that have a demonstrated ability to conduct hyperlocal air quality projects. The bill does not outline what steps should be taken if the air monitoring finds unacceptable levels of pollution in the air. The EPA said it does not comment on potential legislation.

After Markey introduced his version of the bill in July, the Senate referred the legislation to the Committee on Environment and Public Works. There is no vote scheduled for the bill, according to committee aide Jake Abbott.

The legislation “is what communities around industrial facilities have needed for a long time,” Wilma Subra, an environmental health expert, said in an email. Subra has spent her career helping communities struggling with air and water pollution. She said the data from localized air monitoring could tell residents what they’re exposed to and when the pollution exceeds government standards, which could prompt additional scrutiny of industrial polluters.

The House bill was introduced amid a nationwide push for more monitoring of air pollution. In the wake of ProPublica’s “Sacrifice Zones” investigation, the EPA announced that it would establish a new team to conduct aerial monitoring from planes and track emissions on the ground. It pledged to spend more than $600,000 on air monitoring in parts of the southern U.S., such as Mossville, Louisiana, one of the hot spots highlighted in ProPublica’s analysis. The agency also ordered a Louisiana chemical plant to install air monitors along its boundary. These initiatives follow the EPA’s decision last summer to make $50 million in American Rescue Plan funding available to communities interested in improving air quality monitoring. The deadline for applications is March 25.

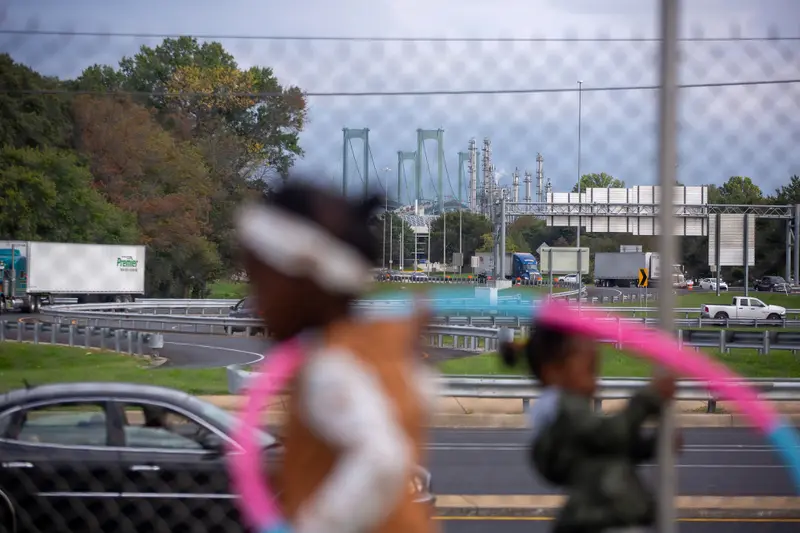

Applying for federal funding, however, can be a lengthy and complex process. Penny Dryden grew up a few miles away from a handful of chemical plants just south of Wilmington, Delaware. Last summer, Dryden worked with community members to set up five handheld air quality monitors in the area after securing a grant from a local health care system. She is now working with a team to apply for EPA funds to expand that effort so that residents and regulators can better understand which chemicals they are breathing and whether more protections are warranted.

“I’ve been at this work for over 30 years, but there were rarely federal funding opportunities, and now here we are, and it is even difficult for me,” said Dryden.

She and others were encouraged by the introduction of this latest bill, which could push agencies and organizations to partner with communities like Dryden’s.

“Hopefully through this bill people can have their voices heard in wanting to understand what’s going on in their community that could be impacting their health and well-being,” said Sheryl Magzamen, a Colorado State University professor who specializes in air quality and health. Magzamen helped ProPublica and Palm Beach Post reporters design the air quality monitoring plan and assess the results of the “Black Snow” project. The work prompted Magzamen to submit a research proposal to NASA, which awarded her team a $218,000 grant to use low-cost sensors and satellite data to better track pollution in Florida’s cane-burning region and other areas.

“Problems are able to be solved when we have data that points us to what the problems actually are, and monitoring is a huge step in the right direction,” Magzamen said.