Each year, people and companies contribute hundreds of millions of dollars to tax-exempt political organizations in an effort to influence elections nationwide. These organizations, commonly known as 527s after a section of the tax code, can raise unlimited sums for political spending. Today, ProPublica is releasing a database that will allow journalists, researchers and others to more easily search 527s’ finances and find patterns.

It’s a wide-ranging trove of data that includes well-known groups such as the Democratic Governors Association, which influences pivotal races nationwide, and many obscure ones, including the Minnesota-based organization Garbage Haulers for Citizen Choice, which says it advocates for local freedom of choice in waste pickup.

While the organizations in our database can affect the outcome of elections, their direct support of political candidates is often limited. This means much of their activity is not regulated by the Federal Election Committee or a state equivalent, and is therefore unavailable on the FEC’s easily searchable website.

The 527s in our database instead file reports with the Internal Revenue Service, much like charities, but their filings do not appear in the same locations as most nonprofits. Instead, they’re published on an entirely separate part of the IRS website that uses a dated, difficult-to-use search tool. But buried behind that clunky interface is some significant and useful information, from the names of organizations’ leaders all the way down to line-item expenditures and contributions.

We got firsthand experience of the utility of this data last year when former ProPublica contributor Ilya Marritz used it to report on corporations that had resumed making donations to the Republican Attorneys General Association after Jan. 6, 2021.

RAGA, one of the largest and most influential 527s, used robocalls to urge then-President Donald Trump’s supporters to march to the Capitol on that day. In the aftermath of the attack, many of RAGA’s reliable donors publicly condemned its actions, but an analysis of the data showed that many of them merely paused their donations and then quietly returned months later. It was only possible for us to understand this after downloading and parsing the hard-to-use dataset.

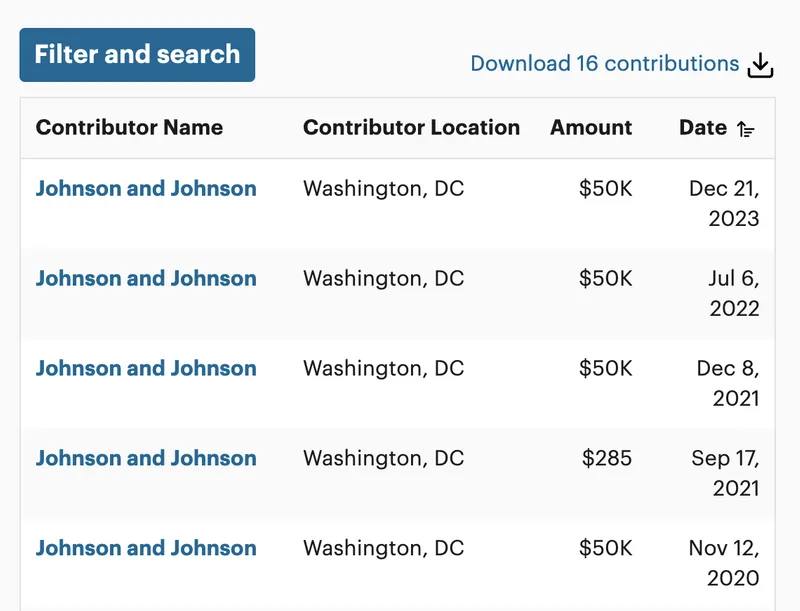

Our new database makes it easy to search all the donations to RAGA and discover how companies like Microsoft not only stopped giving to the Republican group but also halted donations to the Democratic Attorneys General Association. It also makes it obvious that Johnson & Johnson cut a large check to the Republican group later that year.

Despite the influence of many 527s, experts said they receive little scrutiny and are rarely audited. Lloyd Mayer, a professor of law at Notre Dame, says that because these organizations’ filings don’t appear in the same place as those of most other nonprofits or political groups, they aren’t viewed as often. “FEC filings are a lot more searchable and therefore a lot more visible, and therefore it’s easier for reporters to make stories based on those and even for opponents or law enforcement investigators to discover stuff,” Mayer told us.

In this environment, questionable spending often goes unnoticed. ProPublica found a network of 527s that purport to support police, veterans, cancer patients and firefighters, but appear to largely be spending their donation money on a small group of fundraisers and administrative companies that support more fundraising efforts. They’ve raked in millions of dollars from Americans but appear to use little of it for their stated causes.

Last year, The New York Times found a group of 527s that similarly appeared to be putting almost all the money they raised into fundraising and organizations affiliated with the founders. ProPublica identified the network we reported on by looking at similar contributions and expenditures to those going to and from the group that the Times uncovered. In our new database, we’ve created a feature that will show you 527s that appear to have similar donors and expenditures so researchers and the public can do the same thing.

The database helps you find interesting things to dig into further. It makes it easy to see that some organizations withhold the names of large donors, pay most of their money to a single company, or appear to give most of their money back to their largest donors. Whether this behavior is legal often depends on the context, experts say.

The American Dental PAC Education Fund, for example, spent so much money on suites and tickets — about $1.5 million between 2005 and 2020 — to see artists like Taylor Swift and Celine Dion that the company that owns the Capital One Arena in Washington, D.C., makes up about 12% of the PAC’s reported expenditures. According to experts, if the tickets furthered the organization’s purpose, for instance by being used as prizes in a fundraiser, then that is a valid expense. If it is completely unrelated to furthering a political purpose, it would not be. Emails and phone calls to the group were not returned.

Now that this data is more easily explorable, we look forward to seeing what you discover in it. You can drill into state-level data to find the biggest players and largest organizations in your state, or you can take advantage of the powerful search and look up notable people, or sort and filter to see the largest donations made in a year or to a specific organization.

In addition to our similar organizations feature, we’ve added another way to help you uncover connections across organizations. Each contribution and expenditure has its own page, which uses machine learning to show similar contributions and expenditures, allowing you to do things like find other contributions that likely came from Walmart, regardless of minor variations in name or address.

If you write a story using this new information, come across bugs or issues, or have ideas for improvements, please let us know!