Prosecutors routinely find ways to get key detectives to testify in criminal trials, even when they are retired, sick or otherwise reluctant. Some fly retirees in from Florida or other retirement locales when necessary. Others have said they use subpoenas to force detectives to take the witness stand.

But prosecutors in the St. Louis circuit attorney’s office have been unable to get retired homicide detective Thomas W. Mayer Sr. into a courtroom, even though some of the cases Mayer investigated involved the murders of children — the sort of high-profile cases cops say they especially want to win.

Over the past two years, Mayer has told prosecutors he is unable to testify against two men he arrested after the fatal shooting of an unarmed teenager; those cases crumbled. Prosecutors said he told them he’s not available to testify in the case against a teen accused of driving a car from which at least one passenger allegedly shot another teen who was in his own vehicle. And court records say Mayer has been unavailable to testify against a teen charged with the murder of a 9-year-old boy shot while riding in his family’s SUV while they were delivering food to his grandmother.

Mayer, who served as the Missouri president of the Fraternal Order of Police from 1998 to 2006, contends retired police officers should not be expected to testify, because “retirement is meant to be retirement.” And he said his doctor told him he’s too sick to testify, though it’s not the first time Mayer has claimed illness has prevented him from carrying out his duties — and not the first time those claims have been questioned.

“If I were to be dragged back to court, with the stress level and heartbeat level — blump,” Mayer, 66, told a reporter during an interview at his home in rural southeastern Missouri, mimicking a collapse. “I don’t want that.”

Mayer’s position is in some ways similar to that of another retired St. Louis homicide detective, Roger Murphey. ProPublica and Riverfront Times reported last month how Murphey has refused to testify in at least nine murder cases because he was angry over policies of former Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner. Unlike Murphey, Mayer said he was not holding out for political reasons. Still, prosecutors are facing the same challenges to keep his cases viable as they did with Murphey’s.

In a city struggling to solve murders in the first place, the refusal of police to take part in routine court proceedings compounds St. Louis’ criminal justice challenges, and leaves victims shortchanged.

Mayer and Murphey also expose a vulnerability in how St. Louis police approach homicide investigations: They frequently rely on a single detective. But former prosecutors and homicide investigators in other jurisdictions said most police departments use multiple officers at every critical juncture of a case to reduce such vulnerabilities.

“When a homicide case is properly investigated, ideally there should be redundancies built into the investigation so you shouldn’t be reliant on a single police officer for any fact,” said Matt Murphy, who was a prosecutor in Orange County, California, for more than two decades and now works as a defense lawyer and legal commentator.

Mayer said departments should be prepared for retired detectives to be unavailable. “I regret that cases fell by the wayside, but there should be some kind of safety net,” he said in one of a pair of lengthy interviews. He said he believed prosecutors understood his health issues and said they have assured him that “they’re going to go on with other witnesses.”

How Mayer and Murphey have responded to their old murder cases raises questions about why city prosecutors have not dealt with the problem head on, using their subpoena power to force them to court.

Doing so might result in messy trials, with Mayer or Murphey potentially becoming hostile witnesses. But forcing their hands would send a message to the police department that “there are police policy issues that have to get fixed,” said Brendan Roediger, a professor at Saint Louis University School of Law and director of its civil advocacy clinic.

The St. Louis police department did not respond to questions about Mayer and his cases. Marvin Teer, Circuit Attorney Gabriel Gore’s chief trial assistant and the prosecutor who has handled three of those cases, said he had to take Mayer at his word and didn’t have the authority to force him to reveal his medical records. He said Mayer’s health information was protected by privacy laws.

“Our biggest fear,” Teer said, “is he’s already indicated he doesn’t remember the cases because his medicine interferes with his ability to recall accurately. Why do I want to put a guy like that on?”

Teer acknowledged that “in hindsight, I might have done things differently.”

St. Louis has one of the highest homicide rates in the country, with about 1,000 murders since the beginning of 2019. And some families of those who were killed say the refusal of two detectives to testify has compounded their pain.

After Jonathan Cruz, 19, was shot to death in 2021 by passengers in two separate cars, police arrested the alleged driver of one of those cars, Neptali Mejia. Court records show that Mejia provided a videotaped confession to Mayer and that prosecutors charged him with first-degree murder. Mejia has pleaded not guilty and is currently under house arrest.

Cruz’s brother Ivan said he hoped Mejia’s arrest would lead the police to others involved in the crime. Mayer, he said in an interview, “gave me hope there was going to be justice and everyone responsible was going to be behind bars.”

Now the case is in trouble. Because prosecutors have said Mayer won’t testify, Mejia’s lawyer said he plans to ask the judge in the case to block the video recording of Mejia’s statements to Mayer from being admitted at trial.

Ivan Cruz, who said he has moved to another state out of fear of the people who shot his brother, said he was aware that prosecutors were having trouble reaching Mayer. Mayer, he said, “can bring a lot of peace and closure to the families that are suffering from all of this violence.”

The notion that officers would not follow their cases to trial is anathema to many homicide detectives and prosecutors. They said retired police officers, despite generally not being paid for testifying in their old cases, hold a legal and ethical duty to participate at trial, the same as anyone with knowledge pertinent to a court case.

Retired Seattle homicide detective Cloyd Steiger said he belongs to a Facebook group of retired police officers. “I get messages from them sometimes saying, ‘Hey, I got a subpoena for this murder trial. Do I have to go?’” he said. “And my answer is, ‘Yes, it’s unambiguous. Sorry, yeah, you gotta put your big boy pants on and go down there and do it.’”

John Skaggs, a retired Los Angeles homicide detective who trains homicide squads around the country, said the thought that a homicide detective would refuse to testify for any reason “is foreign to me.”

He said he has brought witnesses into court in wheelchairs and even hospital beds because their testimony was so important. He said he would do the same if he was ill and his testimony was needed. “I’d come in with a medical doctor and a paramedic team, and they can revive me if I go out,” he said. “If I’m needed, I’m coming.”

Brian Seaman, the district attorney in Niagara County, New York, said he had to track down seven retired police officers — including two who had moved out of state — to testify in a 2021 trial over the strangling murder of a 17-year-old girl nearly three decades earlier. He won a conviction.

Seaman said that bringing back the retirees was a “logistics puzzle” but that they “took great pride in their work and wanted to see the case through” to a trial. He said if a retired officer is the only witness who can provide testimony about evidence, “it’s just expected that they be available.”

Officers do sometimes have legitimate medical reasons for missing court, experts noted. Or, particularly in cold cases, they may even be dead by the time a case comes to trial. That’s why it’s important that departments have multiple police witnesses for each piece of evidence collected in the investigation.

But in St. Louis, perhaps because the two detectives are alive and their absences cannot easily be explained to jurors, local prosecutors have tried to salvage what they can from them.

Some legal experts took issue with the circuit attorney’s office’s decision not to compel Mayer to court. Murphy, the former Orange County prosecutor, said it would be a “cop-out” for a prosecutor to say they couldn’t proceed with a case because a witness said they were sick. He said prosecutors can subpoena a witness to determine whether they have a valid medical reason not to testify.

In the early morning hours of a Sunday in August 2019, Sentonio Cox became the 12th child that year in St. Louis to be killed by gunfire — and the third that weekend. The 15-year-old had been roaming around a south side neighborhood with a cousin, who was about the same age. The cousin told police later that someone had come out of a house and yelled at them to get off their property. He fled when he heard a gunshot.

The cousin guided the family to the last place he saw Sentonio. Just after sunrise, they found Sentonio’s body in a vacant lot across the street with a gunshot wound to his head.

Mayer led the investigation, which culminated with the arrest of Brian Potter, who lived in a house across from the vacant lot, and Joseph Renick, who had been staying with him. Police and prosecutors alleged the men had confronted the teens after using a surveillance camera to spot them trying to break into a vehicle parked in front of the house.

According to police and court records in the murder cases, Mayer alleged that Renick pointed a revolver at Sentonio as the teen was backing away with his hands up. Potter ordered Renick to “shoot this piece of shit,” and Renick fired one shot into Sentonio’s head. Renick and Potter pleaded not guilty.

Emails obtained through a public record request showed that prosecutors contacted Mayer several times to update him on the case as they prepared for the Renick and Potter trials. Mayer acknowledged in October 2021 that he had received a subpoena, according to the emails.

In January 2022, prosecutor Srikant Chigurupati emailed Mayer to say the trials were coming up and “we’ll obviously need you as a witness.”

Weeks later, prosecutors requested new trial dates, telling Judge Christopher McGraugh that Mayer was on leave from the department and they were unable to get him to testify. The judge denied the requests.

To buy more time to try to get Mayer to court, the circuit attorney’s office in March 2022 dropped the cases and refiled them. Potter’s attorney said the move violated his client’s right to a speedy trial; Renick’s said it was an abuse of the criminal justice system.

By then, Mayer was approaching retirement and using his accumulated sick time. Mayer said he called in sick for several months in 2022, a common practice among St. Louis officers to maximize their payout for unused sick days, and left the department in September of that year, when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 65.

The trial of Potter began in August 2022. Without Mayer, the case against Potter rested on a single eyewitness who had told Mayer she heard Potter give the order to shoot. Potter had told Mayer he didn’t know Renick had a gun, and that the shooting had surprised him, according to testimony at the trial.

Potter’s attorney, Travis Noble, sought to undermine the credibility of that witness, according to the transcript. Noble’s questions during cross-examination revealed that the eyewitness had lied under oath in a previous case and suggested a possible hidden agenda for her implication of Potter: that Mayer had showered her with compliments, called her a hero and promised to intercede with her parole officer. She was on parole for drug trafficking.

Noble also challenged parts of the investigation as unethical and incomplete. In his opening statement, he noted that Mayer, the detective who wrote all the reports, wasn’t there in court but that jurors would instead hear testimony from another detective, Benjamin Lacy, who hadn’t written the reports.

In an exchange with Teer in court, Noble said he would reveal the reason for Mayer’s absence to the jury, insinuating there was more to the story. Out of earshot of the jury, Noble told the judge that he’d heard rumors that Mayer simply “doesn’t want to come back” to testify and said he wanted to ask Lacy about it on the stand, according to the trial transcript.

“He said, ‘F the city of St. Louis,’” Noble told the judge. “He’s riding out, burning his sick time until he can retire.”

The judge said he was wary of derailing the trial by allowing the jury to hear questions about Mayer’s absence. He pointed out that another prosecutor had vouched for Mayer’s medical condition, and he had to accept it as fact. The judge told both sides to say Mayer was “not available.”

In cross-examination, Noble pressed Lacy for details that Mayer had not recorded in his report.

“I know this is not your investigation,” Noble said. “I’m not saying you were derelict the way you did it. This ain’t you. This is Mayer’s investigation, right?”

Lacy answered: “It is.”

The jury acquitted Potter after less than a day of deliberation.

“There was no evidence presented that seemed credible,” the jury foreman, Adam Houston, said in an interview. “Maybe the detective could have made the difference if he had been a credible witness, but it was just some really crappy pictures, a lot of hearsay and random people who are not trustworthy saying things you don’t feel were unmotivated by the things they might be getting out of testifying.”

A week before Renick’s murder trial was set to begin in June, Teer struck a deal for him to plead to involuntary manslaughter; under what’s known as an Alford plea, Renick maintained his innocence even as he conceded prosecutors had enough evidence to convict him. Renick was sentenced to 10 years in prison; under parole guidelines, he is scheduled to be released in August 2025.

While the judge said he didn’t typically discuss plea deals, he described Renick’s sentence as “extremely favorable.” If the case had gone to trial, he said, Renick could have faced life in prison.

Teer said he was “incensed” over how Mayer affected his cases.

Mayer lives far from where he once tried to solve some of the city’s most brutal crimes, in a home set in woods off a dirt road about 100 miles south of St. Louis. Reporters from ProPublica and the Riverfront Times interviewed him in front of his home in June and again in October, each time for about 90 minutes.

Mayer has told prosecutors that he suffers from a heart condition, according to Teer. During the interviews, he said his physical decline should be plainly visible, and he repeatedly apologized for seeming groggy or forgetting key details, which he blamed on the medications he takes. He declined to share his medical records.

This is not the first time Mayer has claimed to be sick for extended periods, but he said that allegations he has abused sick time are false. Before joining the St. Louis police force in 2005, Mayer worked for 24 years in the police department in St. Charles, a major St. Louis suburb. He also took on leadership roles with the FOP, and eventually became its statewide president, representing some 5,000 officers.

In 1995, the St. Charles chief, David King, wrote in an internal memo that Mayer had developed an attitude that “may be counterproductive to police efforts” after his work shift was changed, according to court records.

Mayer then called in sick for 4 1/2 months, producing doctor’s notes that said he had shortness of breath and vocal cord spasms, according to court records. In a memo in January 1996, King noted that Mayer had been seen at an FOP dinner dance and was attending union-related meetings.

In 2003, some St. Charles City Council members wanted to trim Mayer’s benefits, including the 200 hours a year of paid leave he received to do union work. He filed a workers compensation claim for stress-related illness from the “constant and pervasive harassment” of the city council members, then called in sick for five months. His doctor noted that while Mayer was too sick to work, he was able to carry out his FOP duties, which carried “minimal stress,” according to medical records in court papers.

In May 2004, Mayer sued the city, the city administrator and all 10 council members, alleging they were harassing him and causing him health problems. The city countersued with a host of charges against Mayer, including repeated sick time abuse. It pointed to his work for the FOP and claimed that he was physically active.

Mayer was fired in April 2005, according to court records, then months later hired by the St. Louis police department. Mayer and the city of St. Charles agreed to drop their lawsuits, with the city agreeing to pay Mayer $57,000 and describe his departure in personnel records as a retirement, according to news reports.

Fourteen months into his retirement, Mayer recalled how he used to relish testifying in court, a task he called the “crowning jewel” of police work. He said he particularly enjoyed the results of his testimony: helping to send a defendant to prison.

But Mayer said he doesn’t want to think about the horrors of his old job. “That city was just a toilet, and the violence put on other people is just horrendous,” he said. “I don’t really want any involvement anymore,” he added. “I’m retired, you know — aging — and I have my kids and my grandkids.”

That attitude comes with a cost. In the case against Neptali Mejia for the murder of Jonathan Cruz, Mayer’s reluctance to testify casts doubt on the prosecution’s ability to get a murder conviction.

Ivan Cruz said he fears the people involved in his brother’s death will become emboldened if Mejia is not convicted of murder. He said he believes that potential co-defendants have seen Mejia on house arrest and “laugh about it and say the system is not going to do anything.”

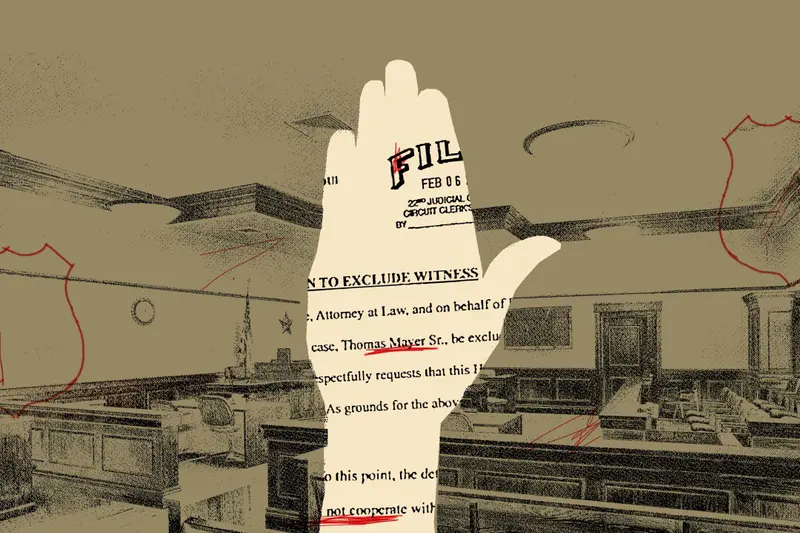

In February, Judge Katherine Fowler granted a motion by Mejia’s lawyer, Mark Byrne, to exclude Mayer from testifying because prosecutors had not made him available for a pretrial deposition. Byrne noted in the motion that the prosecutor had told him and the judge months before that Mayer “has not been cooperative with prosecutions of cases in the City of St. Louis.”

Mayer was the only detective present when Mejia allegedly made statements that prosecutors say implicated him, and prosecutors have not disclosed any witness who could provide evidence against his client, Byrne wrote. It’s not clear if a prosecutor would be able to use the recording of Mejia’s statements at trial without Mayer appearing in court to testify about it.

Byrne said if the case were to go to trial, he would ask the judge to bar the recording because he would not have a chance to cross-examine Mayer about it.

“Any evidence they would try to put on and not have the lead detective is problematic,” he said. “The lead detective has his hands on everything and directs people to do things as part of their investigation.”

Two weeks before publication of this story, Teer said he’d been “troubled for quite some time” about Mayer’s absence from the Mejia case. “You can expect that he’ll receive a subpoena from us,” Teer said.

“And if I have to arrest Tommy Mayer to bring him in,” he added, “then I will.”