The day before doctors had scheduled Amanda Duffy to give birth, the baby jolted her awake with a kick.

A few hours later, on that bright Sunday in November 2014, she leaned back on a park bench to watch her 19-month-old son Rogen enjoy his final day of being an only child. In that moment of calm, she realized that the kick that morning was the last time she had felt the baby move.

She told herself not to worry. She had heard that babies can slow down toward the end of a pregnancy and remembered reading that sugary snacks and cold fluids can stimulate a baby’s movement. When she got back to the family’s home in suburban Minneapolis, she drank a large glass of ice water and grabbed a few Tootsie Rolls off the kitchen counter.

But something about seeing her husband, Chris, lace up his shoes to leave for a run prompted her to blurt out, “I haven’t felt the baby kick.”

Chris called Amanda’s doctor, and they headed to the hospital to be checked. Once there, a nurse maneuvered a fetal monitor around Amanda’s belly. When she had trouble locating a heartbeat, she remarked that the baby must be tucked in tight. The doctor walked into the room, turned the screen away from Amanda and Chris and began searching. She was sorry, Amanda remembers her telling them, but she could not find a heartbeat.

Amanda let out a guttural scream. She said the doctor quickly performed an internal exam, which detected faint heart activity, then rushed Amanda into an emergency cesarean section.

She woke up to the sound of doctors talking to Chris. She listened but couldn’t bring herself to face the news. Her doctor told her she needed to open her eyes.

Amanda, then 31, couldn’t fathom that her daughter had died. She said her doctors had never discussed stillbirth with her. It was not mentioned in any of the pregnancy materials she had read. She didn’t even know that stillbirth was a possibility.

But every year more than 20,000 pregnancies in the United States end in stillbirth, the death of an expected child at 20 weeks or more. That number has exceeded infant mortality every year for the last 10 years. It’s 15 times the number of babies who, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, died of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, or SIDS, in 2020.

The deaths are not inevitable. One study found that nearly one in four U.S. stillbirths may be preventable. For pregnancies that last 37 weeks or more, that research shows, the figure jumps to nearly half. Thousands more babies could potentially be delivered safely every year.

But federal agencies have not prioritized critical stillbirth-focused studies that could lead to fewer deaths. Nearly two decades ago, both the CDC and the National Institutes of Health launched key stillbirth tracking and research studies, but the agencies ended those projects within about a decade. The CDC never analyzed some of the data that was collected.

Unlike with SIDS, a leading cause of infant death, federal officials have failed to launch a national campaign to reduce the risk of stillbirth or adequately raise awareness about it. Placental exams and autopsies, which can sometimes explain why stillbirths happened, are underutilized, in part because parents are not counseled on their benefits.

Federal agencies, state health departments, hospitals and doctors have also done a poor job of educating expectant parents about stillbirth or diligently counseling on fetal movement, despite research showing that patients who have had a stillbirth are more likely to have experienced abnormal fetal movements, including decreased activity. Neither the CDC nor the NIH have consistently promoted guidance telling those who are pregnant to be aware of their babies’ movement in the womb as a way to possibly reduce their risk of stillbirth.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the nation’s leading obstetrics organization, has been slow to update its own guidance to doctors on managing a stillbirth. In 2009, ACOG issued a set of guidelines that included a single paragraph regarding fetal movement. Those guidelines weren’t significantly updated for another 11 years.

Perhaps it’s no surprise that federal goals for reducing stillbirths keep moving in the wrong direction. In 2005, the U.S. stillbirth rate was 6.2 per 1,000 live births. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in an effort to eliminate health disparities and establish a target that was “better than the best racial or ethnic group rate,” set a goal of reducing it to 4.1 for 2010. When that wasn’t met, federal officials changed their approach and set what they called more “science-based” and “realistic” goals, raising the 2020 target to 5.6. The U.S. still fell short. The 2030 goal of 5.7 was so attainable that it was met before the decade started. The 2020 rate, the most current according to the CDC, is 5.74.

By comparison, other wealthy countries have implemented national action plans to prevent stillbirth through awareness, research and care. Among other approaches, those countries have focused on increasing education around stillbirth and the importance of a baby’s movements, reducing rates of smoking and identifying fetuses that grow too slowly in the womb.

The efforts have paid off. The Netherlands, for instance, has reduced its rate of stillbirths at 28 weeks or later by more than half, from 5.2 in 2000 to 2.3 in 2019, according to a study published last year in The Lancet.

Dr. Bob Silver, chair of the obstetrics/gynecology department at University of Utah Health and a leading stillbirth expert, coauthored the study that estimated nearly one in four stillbirths are potentially preventable, a figure he referred to as conservative. He called on federal agencies to declare stillbirth reduction a priority the same way they have done for premature birth and maternal mortality.

“I’d like to see us say we really want to reduce the rate of stillbirth and raise awareness and try to do all of the reasonable things that may contribute to reducing stillbirths that other countries have done,” Silver said.

The lack of comprehensive attention and action has contributed to a stillbirth crisis, shrouded in an acceptance that some babies just die. Compounding the tragedy is a stigma and guilt so crushing that the first words some mothers utter when their lifeless babies are placed in their arms are “I’m sorry.”

In the hospital room, Amanda Duffy finally opened her eyes. She named her daughter Reese Christine, the name she had picked out for her before they found out she had died. She was 8 pounds, 3 ounces and 20 1/2 inches long and was born with her umbilical cord wrapped tightly around her neck twice. The baby was still warm when the nurse placed her in Amanda’s arms. Amanda was struck by how lovely her daughter was. Rosy skin. Chris’ red hair. Rogen’s chubby cheeks.

As Amanda held Reese, Chris hunched over the toilet, vomiting. Later that night, as he lay next to Amanda on the hospital bed, he held his daughter. He hadn’t initially wanted to see her. He worried she would be disfigured or, worse, that she would be beautiful and he would fall apart when he couldn’t take her home.

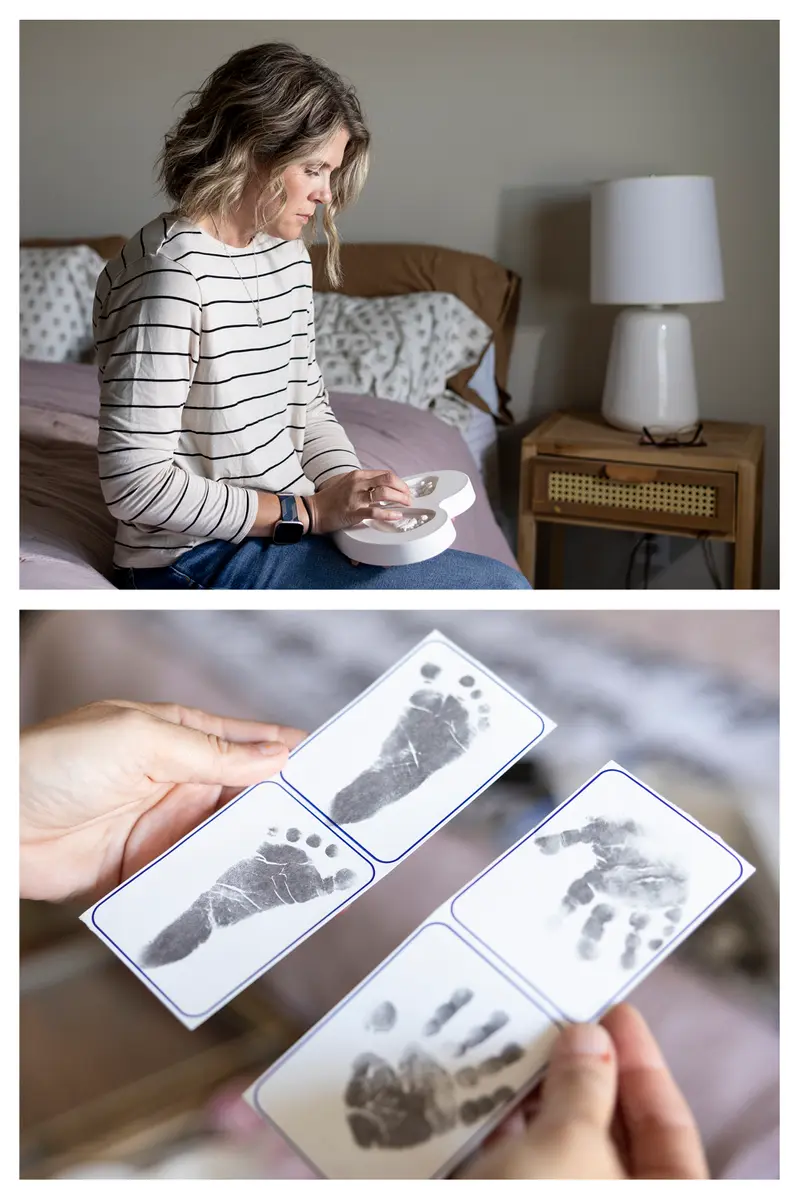

The nurses taught Amanda and Chris how to grieve and love simultaneously. One nurse told Amanda how cute Reese was and asked if she could hold her. Another placed ice packs in Reese’s swaddle to preserve her body so Amanda could keep holding her. Amanda asked the nurses to tuck cotton balls soaked in an orange scent into Reese’s blanket so the smell would trigger the memory of her daughter. And just as if Reese had been born alive, the nurses took pictures and made prints of her hands and feet.

“I felt such a deep, abiding love for her,” Amanda said. “And I was so proud to be her mom.”

On the way home from the hospital, Amanda broke down at the sight of Reese’s empty car seat. The next few weeks passed in a sleep-filled fog punctuated by intense periods of crying. The smell of oranges wrecked her. Her breast milk coming in was agonizing, physically and emotionally. She wore sports bras stuffed with ice packs to ease the pain and dry up her milk supply. While Rogen was at day care, she sobbed in his bed.

In the months that followed, Amanda and Chris searched for answers and wondered whether their medical team had missed warning signs. Late at night, Amanda turned to Google to find information about stillbirths. She mailed her medical records to a doctor who studies stillbirths, who she said told her that Reese’s death could have been prevented. They briefly discussed legal action against her doctors, but she said a lawyer told her it would be difficult to sue.

Amanda and Chris pinpointed her last two months of pregnancy as the time things started to go wrong. She had been diagnosed with polyhydramnios, meaning there was excess amniotic fluid in the womb. Her doctor had scheduled additional weekly testing.

One of those ultrasounds revealed problems with the blood flow in the umbilical cord. Reese’s cord also appeared to be wrapped around her neck, Amanda said later, but was told that was less of a concern, since it occurs in about 20% of normal deliveries. At another appointment, Amanda’s medical records show, Reese failed the portion of a test that measures fetal breathing movements.

At 37 weeks, Amanda told one of the midwives the baby’s movements felt different, but, she said, the midwife told her that it was common for movements to feel weaker with polyhydramnios. At that point, Amanda felt her baby was safer outside than inside and, her medical records show, she asked to schedule a C-section.

Despite voicing concerns about a change in the baby’s movement and asking to deliver earlier, Amanda said she and her husband were told by her midwife she couldn’t deliver for another two weeks. The doctor “continues to advise 39wks,” her medical records show. Waiting until 39 weeks is usually based on a guideline that deliveries should not happen before then unless a medical condition specifically warrants it, because early delivery can lead to complications.

Amanda would have to wait until 39 weeks and one day because, she said, her doctors didn’t typically do elective deliveries on weekends. Amanda was disappointed but said she trusted her team of doctors and midwives.

“I’m not a pushy person,” she said. “My husband is not a pushy person. That was out of our comfort zone to be, like, ‘What are we waiting for?’ But really what we wanted them to say was ‘We should deliver you.’”

Amanda’s final appointment was a maximum 30-minute-long ultrasound that combined a number of assessments to check amniotic fluid, fetal muscle tone, breathing and body movement. After 29 minutes of inactivity, Amanda said, the baby moved a hand. In the parking lot, Amanda called her mother, crying in relief. Four more days, she told her.

Less than 24 hours before the scheduled C-section, Reese was stillborn.

Four months after her death, Amanda, then a career advisor at the University of Minnesota, and Chris, a public relations specialist, wrote a letter to the University of Minnesota Medical Center, where Amanda had given birth to her dead daughter. They said they had “no ill feelings” toward anyone, but “it pains us to know that her death could’ve been prevented if we would have been sent to labor and delivery following that ultrasound.”

They noted that though they were told that Reese had passed the final ultrasound where she took 29 minutes to move, they had since come to believe that she had failed because, according to national standards, at least three movements were required. They also blamed a strict adherence to the 39-week guideline. And they encouraged the hospital staff to read more on umbilical cord accidents and acute polyhydramnios, which they later learned carries an increased stillbirth risk.

The positive feelings they had from speaking up were replaced by dismay when the hospital responded with a three-paragraph letter, signed by seven doctors and eight nurses. They said they had reexamined each medical decision in her case and concluded they had made “the best decisions medically possible.” They expressed their sympathy and said it was “so very heartwarming that you are trying to turn your tragic loss into something that will benefit others.”

Amanda felt dismissed by the medical team all over again. She didn’t expect them to admit fault, but she said she hoped that they would at least learn from Reese’s death to do things differently in the future. She was angry, and hurt, and knew that she would need to find a new doctor.

A spokesperson for the University of Minnesota Medical School told ProPublica she could not comment on individual patient cases and did not respond to questions about general protocols. “We share the physicians’ condolences,” she wrote, adding that the doctors and the university “are dedicated to delivering high quality, accessible and inclusive health care.”

For many expectant parents, it’s hard to muster the courage to call a doctor about something they’re not even sure is a problem.

“Moms self-censor a lot. No one wants to be that mom that all the doctors are rolling their eyes at because she’s freaking out over nothing,” said Samantha Banerjee, executive director of PUSH for Empowered Pregnancy, a nonprofit based in New York state that works to prevent stillbirths. Banerjee’s daughter, Alana, was stillborn two days before her due date.

In addition to raising awareness that stillbirths can happen even in low-risk pregnancies, PUSH teaches pregnant people how to advocate for themselves. The volunteers advise them to put their requests in writing and not to spend time drinking juice or lying on their side if they are worried about their baby’s lack of movement. In the majority of cases, a call or visit to the hospital reassures them.

But, the group tells parents, if their baby is in distress, calling their doctor can save their life.

Debbie Haine Vijayvergiya is fighting another narrative: that stillbirths are a rare fluke that “just happen.” When her daughter Autumn Joy was born without a heartbeat in 2011, Haine Vijayvergiya said, her doctor told her having a stillborn baby was as rare as being struck by lightning.

She believed him, but then she looked up the odds of a lightning strike and found they are less than one in a million — and most people survive. In 2020, according to the CDC, there was one stillbirth for about every 175 births.

“I’ve spoken to more women than I can count that said, ‘I raised the red flag, and I was sent home. I was told to eat a piece of cake and have some orange juice and lay on my left side,’ only to wake up the next day and their baby is not alive,” said Haine Vijayvergiya, a New Jersey mother and maternal health advocate.

She has fought for more than a decade to pass stillbirth legislation as her daughter’s legacy. Her current undertaking is her most ambitious. The federal Stillbirth Health Improvement and Education (SHINE) for Autumn Act, named after her daughter, would authorize $9 million a year for five years in federal funding for research, better data collection and training for fetal autopsies. But it is currently sitting in the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions.

Not all stillbirths are preventable, and medical experts agree more research is needed to determine who is most at risk and which babies can potentially be saved. Complicating matters is the wide range of risk factors, including hypertension and diabetes, smoking, obesity, being pregnant with multiples, being 35 or older and having had a previous stillbirth.

ProPublica reported this summer on how the U.S. botched the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines for pregnant people, who faced an increased risk for stillbirth if they were unvaccinated and contracted the virus, especially during the delta wave.

Doctors often work to balance the risk of stillbirth with other dangers, particularly an increased chance of being admitted to neonatal intensive care units or even death of the baby if it is born too early. ACOG and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine have issued guidance to try to slow a rise in elective deliveries before 39 weeks and the potential harm that can result. The Joint Commission, a national accrediting organization, began evaluating hospitals in 2010 based on that standard.

A 2019 study found that the risks of stillbirth slightly increased after the rule went into effect, but fewer infants died after birth. Other studies have not found an effect on stillbirths.

Last year, the obstetric groups updated their guidance to allow doctors to consider an early delivery if a woman has anxiety and a history of stillbirth, writing that a previous stillbirth “may” warrant an early delivery for patients who understand and accept the risks. For those who have previously had a stillbirth, one modeling analysis found that 38 weeks is the optimal timing of delivery, considering the increased risk of another stillbirth.

“A woman who has had a previous stillbirth at 37 weeks — one could argue that it’s cruel and unusual punishment to make her go to 39 weeks with her next pregnancy, although that is the current recommendation,” said Dr. Neil Mandsager, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist in Iowa and a medical advisor to a stillbirth prevention nonprofit.

At or after 40 weeks, the risk of stillbirth increases, especially for women 35 or older. Their risk, research shows, is doubled from 39 weeks to 40 and is more than six times as high at 42 weeks. In 2019 and 2020, a combined 1,200 stillbirths occurred between 40 and 42 weeks, according to the most recent CDC data.

Deciding when a patient should deliver entails weighing the risks to the mother and the infant against a possible stillbirth as the pregnancy continues, said Dr. Mark Turrentine, chair of ACOG’s Clinical Consensus Committee-Obstetrics, which helped create the guidance on managing a stillbirth. He said ACOG has addressed stillbirth in other documents and extensively in its 2021 guidance on fetal surveillance and testing, which is done to reduce the risk of stillbirth.

ACOG said it routinely reviewed its guidance on management of stillbirth but was unable to make significant updates “due to the lack of new, evidence-based research.” While prevention is a great concern to ACOG, Turrentine said it’s difficult to know how many stillbirths are preventable.

He said it’s standard practice for doctors to ask about fetal movement, and ACOG updated its guidance after new research became available. Doctors also need to include patients in decision-making and tailor care to them, he said, whether that’s using aspirin in patients at high risk of preeclampsia — a serious high blood pressure condition during pregnancy — or ordering additional tests.

After Reese’s death, Amanda and Chris Duffy wanted to get pregnant again. They sought out an obstetrician-gynecologist who would educate and listen to them. They set up several consultations until they found Dr. Emily Hawes-Van Pelt, who was recommended by another family who had had a stillbirth.

Hawes-Van Pelt cried with Amanda and Chris at their first meeting.

“I told her I was scared to be involved,” Hawes-Van Pelt said. “It’s such a tricky subsequent pregnancy because there’s so much worry and anxiety about the horrible, awful thing happening again.”

Amanda’s fear of delivering another dead baby led to an all-consuming anxiety, but Hawes-Van Pelt supported her when she asked for additional monitoring, testing and an early delivery.

When Hawes-Van Pelt switched practices midway through Amanda’s pregnancy, Amanda followed her. But the new hospital pushed back on the early delivery.

“We intervene early for poorly controlled diabetes,” Hawes-Van Pelt said. “We intervene early for all sorts of medical issues. Anxiety and prior stillbirth are two medical issues that we can intervene earlier for.”

Hawes-Van Pelt said she learned a lot from caring for Amanda, who made her reevaluate some of her own assumptions around stillbirths.

“I had a horrible fear of scaring women unnecessarily, and then realized that I was just not preparing women or educating them because of my own fears around it,” she said. “If you can carry a human being in your body and birth that human being and take care of it, you can hear those words.”

The hospital eventually agreed to let Hawes-Van Pelt schedule Amanda for a 37-week C-section. But after Amanda was again diagnosed with polyhydramnios, she went in for a C-section even earlier. She gave birth in 2015 to a healthy boy she and Chris named Rhett. Two years later, Amanda and Hawes-Van Pelt followed the same pregnancy plan, and she delivered a girl named Maeda Reese. Amanda chose the name because, when said quickly, it sounds like “made of Reese.”

Federal agencies, national organizations and state and city officials have mobilized in recent years to address maternal mortality, when mothers die during pregnancy, at delivery or soon after childbirth. They have focused on improving data collection, passing legislation and creating awareness campaigns that encourage medical professionals and others to listen when women say something doesn’t feel right.

In 2017, ProPublica and NPR documented the U.S. maternal mortality crisis, including alarming racial disparities.

According to CDC data, Black women face nearly three times the risk of maternal mortality. They also are more than twice — and in some states close to three times — as likely to have a stillbirth than white women, meaning not only are Black mothers dying at a disproportionate rate, so are their babies.

Janet Petersen, a state senator from Iowa, said it gives her hope to see how the country has turned its attention to maternal mortality and disparities in health care. She simply cannot understand why stillbirth isn’t being met with the same urgency.

In 2020, the CDC reported 861 mothers died either while pregnant or within six weeks of giving birth. That same year, 20,854 babies were stillborn.

Stillbirth, Petersen said, is a missing piece of the puzzle. Research shows the likelihood of severe maternal complications was more than four times higher for pregnancies that ended in stillbirths, and mothers who died within six weeks of delivery were more likely to have had a stillbirth.

“We see it over and over again that stillbirth is one of the maternal health care issues that continuously gets ignored,” said Petersen, a Democrat.

Petersen was a young legislator in 2003 when her daughter Grace was born still. Devastated, she thought of her grandmother, who lost a baby to stillbirth in 1920, just a few weeks before women got the right to vote.

“I was laying in my hospital bed thinking, ‘How could this still be happening in our country?’” Petersen recalled. “And it seemed, from the medical perspective, that, well, stillbirth happens. We can’t do anything to prevent them.”

Over the next few months, Petersen heard from other mothers who had lost their babies and wanted to spark change. As an elected official, Petersen was in a position to do that. In 2004, she introduced legislation that required the Iowa Department of Public Health to create a stillbirths work group, later securing funding through the CDC to create a stillbirth registry.

But the CDC didn’t renew the funding and never analyzed the data from the registry, though a CDC spokesperson said the Iowa Department of Public Health examined the data. Officials from the department did not respond to requests for comment.

Petersen and her fellow mothers pivoted. After hearing how researchers in Norway were able to increase awareness around fetal movement, they co-founded a nonprofit aimed at doing the same in the U.S.

The group, Healthy Birth Day, created colorful “Count the Kicks” pamphlets — and later an app — teaching pregnant people how to track a baby’s movements and establish what is normal for them. Monitoring a baby’s movements is the earliest and sometimes only indication that something may be wrong, said Emily Price, chief executive officer of Healthy Birth Day. One of the organization’s main messages is for pregnant people to speak up and clinicians to listen.

“Unfortunately, there are still doctors who brush women off or send them home when they come in with a complaint of a change in their baby’s movements,” Price said. “And babies are dying because of it.”

One Indiana county, which recorded 65 stillbirths from 2017 through 2019, reported that 74% had either some chance or a good chance of prevention, according to St. Joseph County Department of Health’s Fetal Infant Mortality Review program. For mothers who experienced decreased fetal movement in the few hours or days before the stillbirth, that estimate jumped to 90%.

Although there is not a scientific consensus that kick counting can prevent stillbirths, national groups, including ACOG, recommend that medical professionals encourage their patients to be aware of fetal movement patterns. ACOG also advises medical professionals to be attentive to a mother’s concerns about reduced movement and address them “in a systematic way.”

One complaint the CDC hears too often, an agency spokesperson said, is that pregnant people and those who gave birth recently find that their concerns are dismissed or ignored. “Listening and taking the concerns of pregnant and recently pregnant people seriously,” she said, “is a simple, yet powerful action to prevent serious health complications and even death.”

The CDC, she said, is “very interested” in expanding its research on stillbirth, which is “a crucial part of the development of any awareness or prevention campaigns.” In addition to working to improve its stillbirth data quality, the agency has funded some pilot programs at the city and state level to better track stillbirths, survey people who have had a stillbirth and research risk factors and causes. The Iowa registry, she said, led the CDC to fund different research projects in Arkansas and Massachusetts, which are ongoing.

In 2009, the CDC acknowledged that fetal mortality remained a “major, but often overlooked, public health problem.” Officials wrote that much of the public health concern had been focused on infant mortality “in part due to lesser awareness of the magnitude of fetal mortality, its causes, and prevention strategies.”

But little has changed over the past 13 years. Echoing its earlier message, the CDC this year declared that “much work remains” and that “stillbirth is not often viewed as a public health issue, so increased awareness is key.”

A spokesperson for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which is part of the NIH, said the agency has continually funded research on stillbirths, even after one of its key studies ended. The agency, she said, also supports research on conditions that increase the risk of stillbirth.

As a scientific research institute, it does not issue clinical guidelines or recommendations, she said, though it did launch the Safe to Sleep campaign in 1994, two decades after Congress put it in charge of SIDS federal research efforts. That campaign, which educates parents and caregivers on ways to reduce the risk of SIDS, highlights recommendations issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics. She said the agency will continue to collaborate with organizations that raise awareness about stillbirth and other pregnancy complications “to amplify their messages and efforts.”

“NICHD continues to support research on the prevention, causes, frequency, and risk factors of stillbirth,” the spokesperson said in an email. “Our commitment to enhancing understanding of stillbirth and improving outcomes focuses on building the scientific knowledge base.”

But getting laws on the books that could raise awareness around stillbirth — even when they don’t require additional funding — has been a struggle. Petersen and Price are pushing Congress to pass legislation that would add stillbirth research and prevention to the list of activities approved for federal maternal health dollars.

Though the bill doesn’t ask for any additional funding, it has not yet passed.

In addition, the SHINE for Autumn Act breezed through the House of Representatives in December 2021. After Haine Vijayvergiya, the New Jersey mother who has championed it, secured bipartisan support from U.S. Sens. Cory Booker, D-N.J., and Marco Rubio, R-Fla., she thought the most comprehensive stillbirth legislation in U.S. history would finally become law.

Neither bill has sparked controversy.

But months after press releases announced the SHINE legislation and referred to the U.S. stillbirth rate as “unacceptable,” lawmakers and the families they represent are running out of time as this session of Congress prepares to adjourn.

“From the day that the bill was introduced into the Senate,” Haine Vijayvergiya said, “approximately 13,000 babies have been born still.”

Last month, on a brilliant fall day much like the one when Reese was stillborn, Amanda Duffy bent down to kiss her son Rogen’s head before they walked on stage.

She wore a soft blue T-shirt tucked into her jeans that read “Be courageous.” The message was as much for her as it was for the crowd on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., many of them like her, mothers who didn’t know stillbirth happened until it happened to them. Since Reese’s death, she has coached doctors and nurses on improving care for patients who have suffered pregnancy loss. Among her many suggestions, she tells them their first words when a concerned patient reaches out should be “I’m so glad you called.”

A few hundred people had gathered for The Big PUSH to End Preventable Stillbirth, billed as the first-ever march on the issue. As part of an art installation, Amanda wrote a note to Reese: “You’re pretty magical & for that I’m grateful. You’re a change maker and you are so very loved. Love, Mama.” Before she slipped the folded paper into a sea of more than 20,000 baby hats, Rogen added his own message: “Hope you are having a good time — Rogen.”

Reese would have turned 8 this month.

Before Amanda spoke, she took a deep breath and silenced her nerves. She walked onto the stage and called on Congress to pass the stillbirth legislation before it. She didn’t ask. She demanded.

“It’s time to empower pregnant people and their care providers with information that leads to prevention,” she insisted.

With the afternoon sun bearing down, Amanda and Rogen disappeared into the crowd of families marching toward the Capitol. Many carried signs. Some pushed empty strollers. Amanda was still wearing the orange-scented oil she had rubbed on her wrists that morning.