This article was co-published with Alive in Afghanistan, a news agency launched in the days after the fall of Kabul, aimed at bringing the perspective of the most marginalized Afghans to the world.

Days before the final withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan, thousands of desperate Americans and Afghan allies seeking to flee the country were using unguarded routes across open fields and through narrow alleys to reach one of the only gates providing access to the Kabul airfield.

Despite intelligence warning of terrorist attacks, U.S. military commanders encouraged use of the routes. Some U.S. officials even provided maps to evacuees trying to bypass Taliban fighters stationed at a checkpoint outside the airport.

It was a decision born of necessity, senior military officials told Alive in Afghanistan and ProPublica. The U.S. had publicly committed to helping the tens of thousands of Afghans who had worked on its behalf to safety. The choice was stark. The government’s hold on Afghanistan was collapsing far sooner than intelligence agencies had expected, and the U.S. was forced to improvise a way to evacuate more than 120,000 people in a chaotic environment barely controlled by its remaining forces.

The Taliban controlled the outer checkpoints and were preventing Americans and Afghan civilians from getting to the airport entrance known as Abbey Gate, according to military officials. Commanders on the ground had to weigh the safety of American forces posted at the gate against concerns about leaving behind U.S. citizens and Afghan allies.

On Aug. 26, U.S. intelligence issued warnings of an imminent threat at the airport. That evening, a man loaded with explosives “likely” used one of the unguarded routes to gain access to Abbey Gate, according to a military investigation reviewed by the news organizations. He detonated his suicide device, killing 13 American servicemembers and an estimated more than 160 Afghan civilians.

“This was not the original way it was intended to work,” a senior military official familiar with the investigation told the news organizations, suggesting the compressed timeframe of the evacuation led to the decision to leave the routes unimpeded.

Alive in Afghanistan and ProPublica recently interviewed several Kabul-based doctors who believed they saw gunshot wounds in civilians coming from Abbey Gate. In response to questions, senior military officials provided a preview of their inquiry into the attack, which found there was no evidence civilians had been shot. The officials allowed the news organizations to interview officers familiar with the investigation and view previously unreleased video and drone footage.

At a press briefing Friday, Pentagon officials said that three commanders huddled near the gate roughly 30 minutes before the bombing. The commanders discussed the deteriorating situation on the ground and the possibility of closing the gate. Brig. Gen. Lance Curtis, who led the investigation, declined to elaborate on what decisions, if any, were made.

Taken together, the new information provides the most detailed look yet at the Pentagon’s evolving story of what happened at Abbey Gate that day. Young Marines and Afghan families were exposed to extraordinary danger as a result of a hastily executed evacuation that left ground commanders with hard decisions and limited options.

Ultimately, investigators determined that the attack was “not preventable” without undermining the evacuation mission.

The investigation also provides insight into how the military made a striking reversal of its assessment of the damage done by gunfire that followed the blast. Initially, top officials told the public that Islamic State fighters opened fire on the Marines. Now, the Pentagon has concluded that there was no enemy gunfire. American and British troops fired their weapons, but they didn’t hit any of the thousands of Afghans crushed against the gate seeking refuge, officials said.

The investigation and its conclusions are likely to raise new questions about the Biden administration’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan as the Taliban rapidly retook the country. The suicide bombing at the gates of the airport was one of the deadliest attacks on American forces in the 20-year history of the war. In addition to those who lost their lives, 45 U.S. service members and an estimated 200 or more Afghans were wounded.

With the date of the final withdrawal approaching, tens of thousands of Americans, green card holders and other Afghans flooded toward the Kabul airport, which was surrounded by high walls with entrances at locations around the perimeter.

The crowd pressed against the gates, some attempting to jump the fences while others passed children over the walls to Marines and members of NATO forces inside the airfield. As the situation grew ever more desperate, commanders leading the evacuation decided to shut down all of the main airport entrances on Aug. 25 except Abbey Gate.

Each gate had to close due to its own unique vulnerability, the officials explained. At the northern entrance, three roads converged to provide “high-speed approaches” susceptible to a car bomb. The eastern gate sometimes required an entire squad to evacuate a single civilian because the Marines decided they could only safely bring in one person at a time.

“The reality is that Abbey Gate was the least risky of all the gates,” one official said.

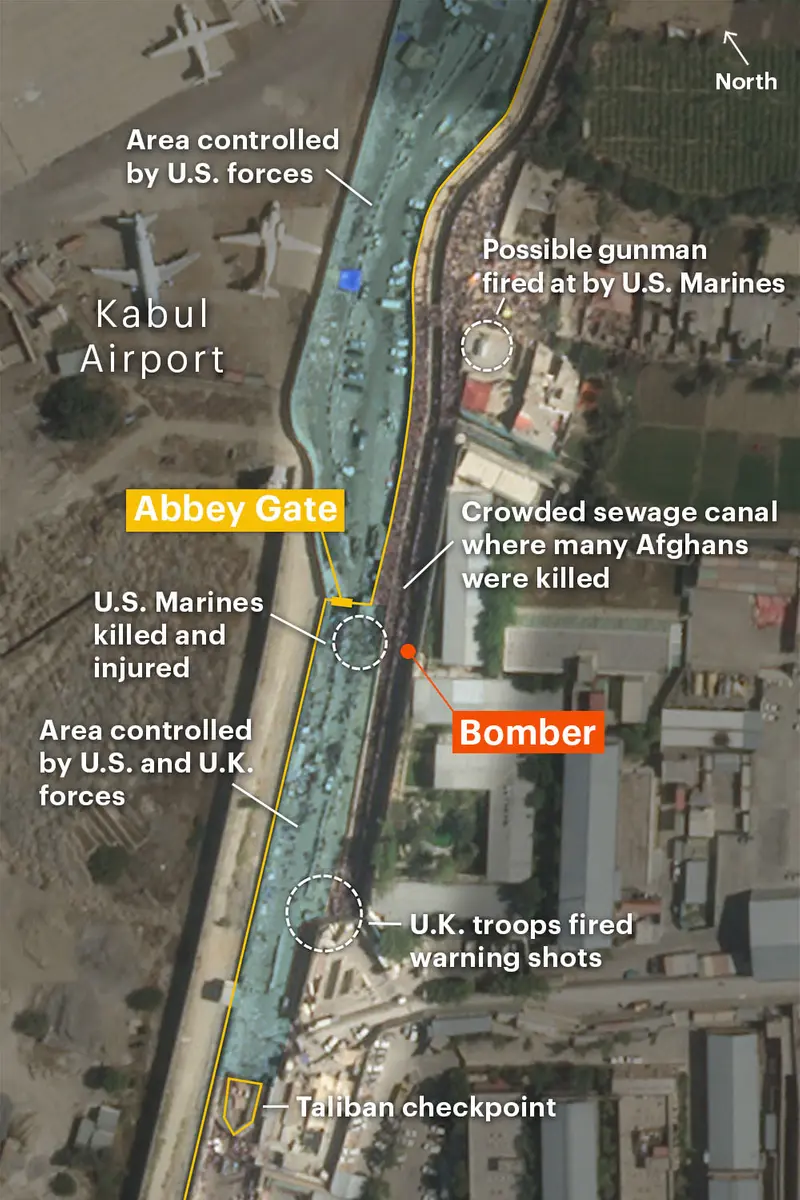

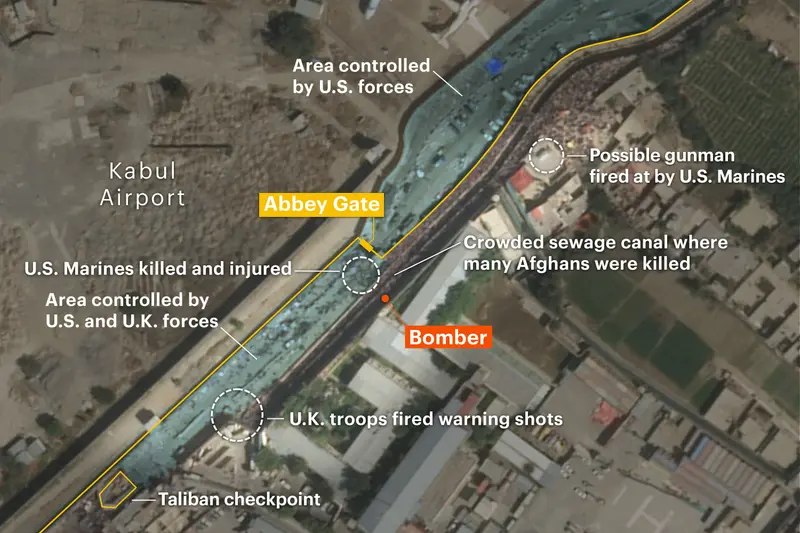

Alongside dozens of U.S. Marines positioned at the gate, U.S. Army soldiers looked on from a tower inside the airport walls. British troops staffed checkpoints and watchtowers to the southwest. And, in an uneasy alliance, Taliban militants worked with allied troops, guarding the perimeter and controlling the access of civilians into the airport.

The Marines positioned a cluster of shipping containers at the end of an entry road to the gate to form what became a Taliban-controlled checkpoint. Past the checkpoint, the area around the gate had natural advantages. The long, narrow path to it was divided in the middle by a sewage ditch, which provided some measure of crowd control. Several surrounding towers offered key vantage points for American and British troops.

But the protections only held up for so long. As the numbers of people grew, more Marines were needed to form a human barrier to hold back the crowd. They were forced into a tight clump, increasing their vulnerability to attack. At the same time, they had to act as de facto immigration officers, examining documents to determine who to allow to pass through the gate into the airport. Soon, the sewage ditch was filled with desperate Afghans, holding up paperwork and pleading with the junior Marines who lined the canal wall.

A video obtained by the military showed the moment of the attack: At 5:36 p.m., a figure dressed in black took a single step out of the crowd and disappeared in a plume of smoke. A Marine in the frame was staggered by the blast wave, which traveled as far as about 50 meters, the senior military officials said.

In the moments after, investigators determined, American and British troops then fired from four positions surrounding Abbey Gate.

Two British troops fired roughly 30 warning shots into the air, the investigation found. One Marine fired four warning shots over the head of what investigators called a “suspicious individual” and said he saw him run away unharmed. Another Marine fired fewer than 30 rounds at an adult male allegedly holding an AK-47, who was positioned on a rooftop to the east.

“What they don’t see is a hostile act,” said a senior official familiar with the investigation. “They don’t see him firing.” Investigators were unable to determine who the man was or what happened to him. The investigation said it was unlikely he shot at Marines, and that if he did, he was most likely a “rogue Taliban member.”

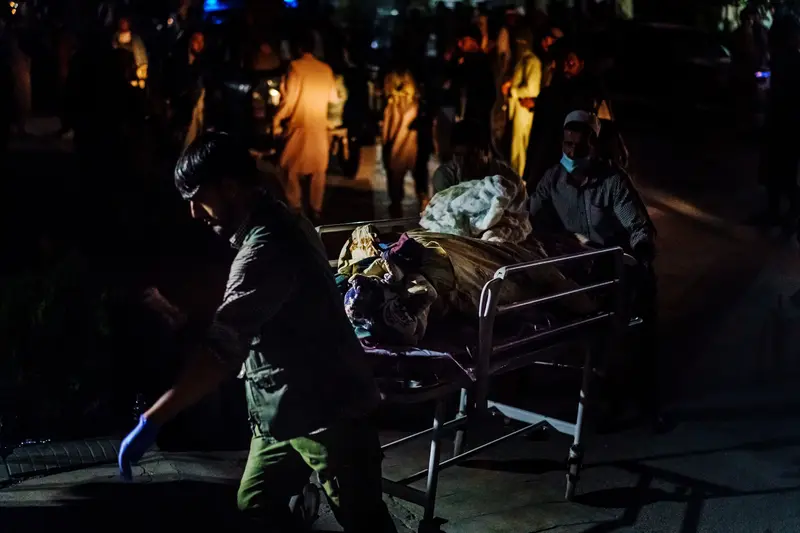

After the gunfire ceased, Marines began to rush casualties — injured and dying Marines and civilians — into the airport for treatment. In the hurried operations that followed, military doctors assessed that many of the injured and dead had been shot. The doctors treated U.S. service members and dozens of Afghan civilians.

After consulting military medical examiners, the investigators determined the doctors were mistaken in their assessment of what they thought were gunshot wounds. None of the doctors recovered bullets from any patients. What the doctors thought were bullet holes were actually caused by ball bearings exploding from the suicide bomber’s device, the investigation concluded. Blast experts interviewed by ProPublica and Alive in Afghanistan said that these metal balls can produce wounds that look extremely similar to those caused by bullets.

ProPublica and Alive in Afghanistan spoke to six doctors from three different Kabul hospitals about their experience treating civilians in the aftermath of the attack. The doctors remained convinced that they saw wounds from bullets, not only ball bearings. All said they had the experience necessary to make the distinction, having responded to numerous terrorist attacks and firefights in their medical careers.

Their accounts suggest a potential gap in the Pentagon’s inquiry. The investigation concluded there was no evidence that civilians had been shot by anyone. But the investigators never spoke to any of the local, Kabul-based physicians who treated the majority of civilians.

Doctors with Emergency Surgical Centre, a well-regarded, Italian-run facility in Kabul that specializes in the treatment of war victims, said they received 10 people with fatal injuries from gunfire.

Eight were shot in the head or neck, they said. The others were shot in the chest. The doctors said they also treated patients with gunshot wounds.

“It was really a disaster situation,” said Dr. Mir Abdul Azim, a senior surgeon on duty that night who has worked at Emergency for 15 years. Azim did not find any bullets in his patients or the dead. But he said he could tell that the wounds were caused by bullets and not ball bearings from the shape and size of the entry and exit wounds, along with other factors such as the tissue damage he saw.

Dr. Hares Aref, a senior surgeon at Wazir Akbar Khan Hospital, one of Kabul’s largest public hospitals, said he personally operated on three patients with bullet wounds in their legs. “We had patients with bullet injury in this attack, it’s clear,” he said. Aref said that the distinction between ball bearing and bullet wounds is clear to him after witnessing multiple similar mass casualty events in Kabul. “My proof is my experience.”

Dr. Rafi Amiri, a surgeon in charge of the same hospital’s emergency department that night, described a visual inspection of dozens of dead Afghans at the hospital morgue. For many of them, he wrapped their heads in cloth, following an Afghan tradition of preparing bodies for burial. A number of them had what appeared to be gunshot wounds. “Their bodies were intact,” he said. “They only had a bullet wound to the head or the chest.”

In the interview, Amiri repeatedly cautioned that he did not conduct a forensic examination and said he was not interested at the time in determining a cause of death.

Pentagon officials dismissed doctors’ external assessments of wounds as scientifically inconclusive. Only an autopsy “could produce definitive results,” said Capt. Bill Urban, a spokesperson for U.S. Central Command.

Urban also said the ball bearings used in the bombing were almost the same size as bullets used by American troops, adding to the potential for confusion.

Dr. David King, a trauma and combat surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Trauma Center, treated victims of the Boston Marathon bombing, in which terrorists used improvised explosive devices loaded with ball bearings and nails. In an interview, he told Alive in Afghanistan and ProPublica that it was very difficult to distinguish wounds from gunshots versus ball bearings.

“As a generalization, I would say that with a high degree of confidence, looking at the hole alone, you largely, generally cannot tell the difference,” he said.

Michael Cardash, a former deputy head of the Israeli National Police Bomb Disposal Division, has examined bomb attacks for more than 30 years. In an interview, he said that some experienced war zone doctors can distinguish such wounds on sight.

“If he’s a doctor in Kabul, he has probably seen gunshot wounds before,” he said. “I would say, if he is an experienced doctor, he probably knows what he is talking about.”

The military has collected additional evidence that it says disproves allegations of a mass shooting.

The Pentagon investigators conducted interviews with 139 American and British personnel about the incident, according to Urban. “Not a single individual described wanton or reckless shooting post attack,” he said.

While there were “a small number of inconsistencies in the sworn testimony of some of the witnesses interviewed,” Urban said, investigators attributed them to the inexperience of some Marines and the effects of the blast, which left nearby troops disoriented or concussed.

Military officials showed drone footage of the blast site to ProPublica and Alive in Afghanistan reporters. Asked why there was no overhead video of the gate at the time of the blast, the officials said it was because drones were monitoring the airstrip and other “classified threats.” They declined to elaborate. The footage starts three minutes later. The camera bounces between Abbey Gate and other locations around the airport. When it focuses on the gate, no gunfire is clearly visible.

“While this video is not definitive proof that no one was shot during periods of time when the scene was not observed by overhead cameras, they did conclusively demonstrate that the scene of the explosion was not the site of a mass shooting,” Urban said. “Such an incident would have caused panicked fleeing that continued long after the shooting ended and the likes of which were never observed by any video.”

The investigators’ findings are substantially different from the Pentagon’s initial version of events. The day of the bombing, Gen. Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr., the leader of Central Command, said that Islamic State gunmen fired at Marines and the crowd. Three weeks later, Maj. Ben Sutphen, operations officer for the battalion at the gate, appeared on CBS News with his own firsthand account.

“He’s blown off his feet,” Sutphen said of a corporal under his command who was knocked over by the blast. “Shot through the shoulder, immediately recovers his weapon and puts the opposing gunman down.”

Urban said Sutphen’s account was “based upon the events as they were shared with him as opposed to his recollection of the events” and that he later told investigators “he may not have been remembering the event correctly.” Urban also said that people close to a bombing can suffer concussions that impair their recall, and thus can “unconsciously” use secondhand information “to fill in the gaps of their memory.”

Update, Feb. 4, 2022: This story has been updated to include information released in a Pentagon press briefing on Friday.

Alex Mierjeski and Doris Burke of ProPublica contributed research.