This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Oregon Public Broadcasting. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

April 2022, early spring Chinook season

Last year’s tribal catch: 1,605,000 lbs (worst spring season in 22 years)

The salmon were late and the nets were empty.

Two weeks had passed since the Yakama Nation opened its ceremonial and subsistence spring fishing season on the Columbia River. Randy Settler and Sam George had spent $400 on gas for their boats, and had just two fish so far to give to their tribe for ceremonies.

This year’s salmon fishing was forecast to be better than last year’s. But it was the slowest start to a season that Settler could remember. It was also his first season without his mother, Mary Goudy-Settler, who died in October 2021.

Settler was sitting in the riverside house that used to be hers, reflecting on all that had been taken from his family, all his parents had done to claw back what they could. They had fought for their right to fish, a right the U.S. government promised to honor more than 150 years ago and then violated generation after generation through laws, policies and flat-out discrimination. He inherited that fight. Now, with climate change threatening the remaining salmon runs, he thinks about the legacy they left for him, the one he’ll pass down to his nephew, George, and to George’s 10-year-old daughter.

“Áwna sɨ́nwit UllaQut’.” His eyes welled up when he introduced himself by the Yakama name his mother gave him.

“But I’ve never claimed that name,” Settler, 67, later said.

The name, UllaQut’, translates to “frog.” It means more than that.

Mary Goudy-Settler and tribal elders bestowed it in a traditional ceremony when her son was 42, the same year he was elected to the governing council of their tribe.

It is a variant on the name of a famous war chief, one that Settler is tied to through his family’s lineage. To carry that name, he said, “you have to be a big deal in Indian Country.”

He has spent a lot of his life trying to live up to it.

June 1855, spring Chinook season

Estimated yearly catch: Over 10,000,000 lbs

Settler’s great-great-great-grandfather was one of the signers of the treaties.

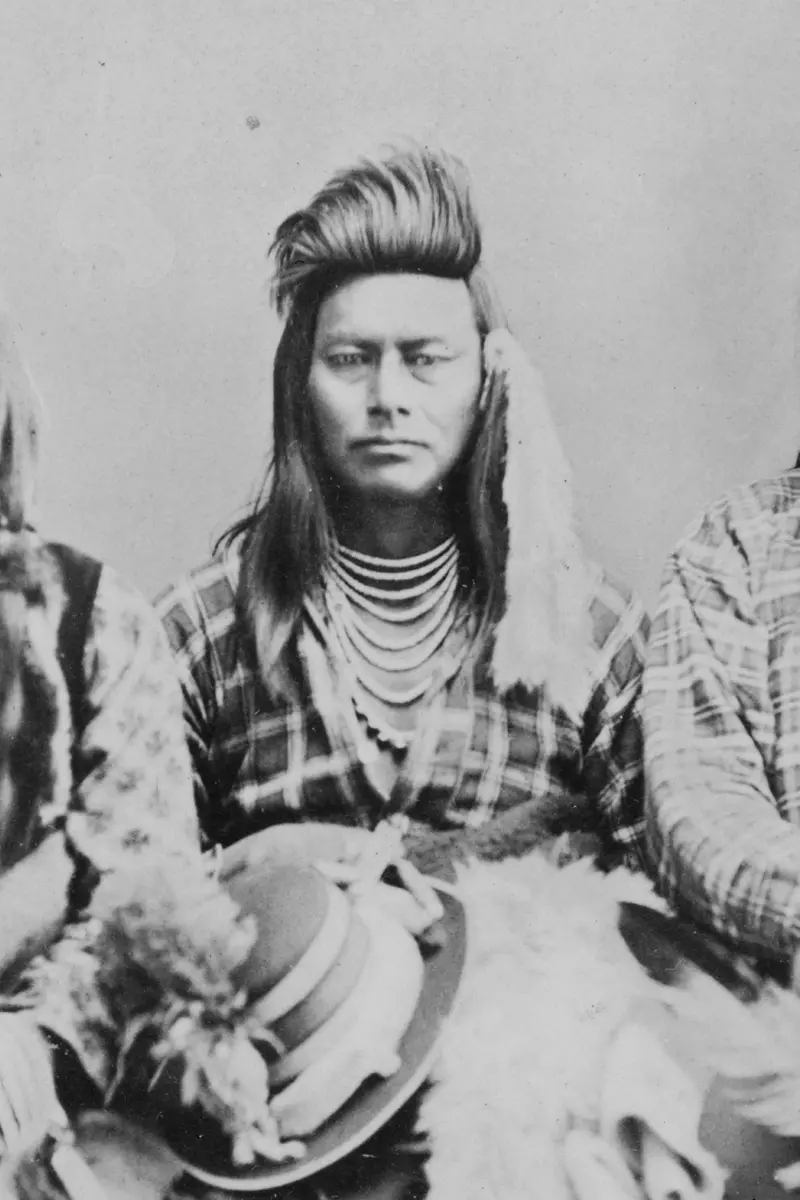

Tuekakas, also known as Old Chief Joseph, chief of the Wallowa band of the Nez Perce, had been an early adopter of Christianity among Native people and an advocate of peace with white settlers. He brought his sons with him to the treaty council: Young Joseph and Ollokot, the original Frog.

But the chief’s faith in that peace was shaken when, a few years after the 1855 treaty, the U.S. government seized nearly all of the tribe’s remaining land. It claimed this was permitted under a new treaty that had been signed by other members of the Nez Perce.

Tuekakas refused to acknowledge the new treaty. He tore up the Bible he’d been given by missionaries, disavowed the government and gave his sons a warning: “When you go into council with a white man, always remember your country,” he told them. “Do not give it away. The white man will cheat you out of your home.”

After their father’s death, Ollokot’s older brother became the tribe’s recognized leader, later to achieve fame as Chief Joseph. Ollokot became a war chief. After their band of the Nez Perce refused to move to a smaller reservation, the U.S. Army hunted them down.

Ollokot led severely outnumbered Nez Perce warriors to many victories in battle, repeatedly fending off U.S. forces that pursued them for more than 1,000 miles as they fled toward safe haven in Canada.

U.S. troops finally overwhelmed the Nez Perce 40 miles from the Canadian border. There, at the Battle of Bear Paw on Sept. 30, 1877, Ollokot was killed.

His brother, the chief, surrendered within the week. The surviving Nez Perce weren’t allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest for another 10 years.

Across the Columbia Basin, tribes had been left with just a sliver of their lands. The treaties still protected their right to fish, but that was not to last.

March 1957, spring Chinook season

Yearly catch at Celilo Falls (pre-dam): 1,894,000 lbs

In the run-up to dam construction, the federal government forced Native people out of fishing villages along the Columbia.

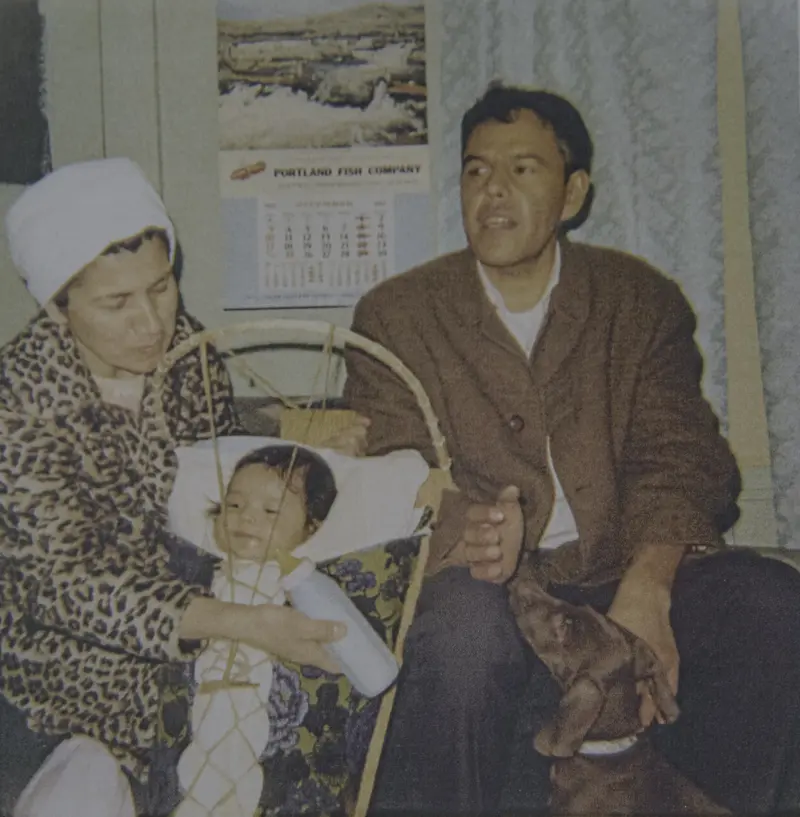

Alvin Settler and Mary Goudy-Settler were relocated to the Yakama’s inland reservation and told to try farming. But they weren’t farmers. They struggled to feed their four children and themselves.

Alvin knew The Dalles Dam would mean the destruction of Celilo, and the end of the way he and his family had always fished. He also needed money.

So he went to work building the dam.

“They did it for survival,” Randy said of his father and other relatives who helped build the dam.

Several years after the dam was completed, the Settlers returned to the river, even without Celilo, for the only life they knew: fishing.

They settled in a shanty village called Lone Pine, in the shadow of The Dalles Dam. It was one of 31 treaty fishing access sites the government offered tribes after damming and destroying their usual fishing grounds.

Randy remembers finding spearheads and beadwork in the dirt where he played and thinking about how old they might be.

The government forbade people from building permanent homes on those sites. So, on the banks of the river that had long ago made their families wealthy, the Settlers and their four kids made their home in a corrugated tin shed built for drying salmon.

“If the sun was out, we roasted. When it was cold, we froze,” Randy said.

Throughout Randy’s grade school years, they lived, cooked and slept in that one-room shed with no electricity and no running water.

He remembers showing up dirty to school, where he and the other kids from Lone Pine would be stripped down and showered off in the boiler room.

They drank river water, bathed in river water and lived off what they could catch, eating fish or selling it to afford fruit and potatoes.

“When we had fish, we could eat. When we didn’t have fish, we pretty much starved,” Settler said.

When boat hulls or engines needed repair, the family couldn’t buy food. Randy remembers an $1,800 boat repair bill that prompted him and his older brother, Carl, to learn how to work with fiberglass themselves. The youngest of four siblings, Randy began operating his own boat when he was 9.

His parents, along with fellow fishing families at the river, started getting more assertive about their rights to catch and sell fish, defying the many state regulations meant to limit their ability to do so.

“It was a war for survival,” Settler said.

The Fish Wars, as they are often known in the Northwest, were about to begin.

April 1966, spring Chinook season

Yearly catch: 294,000 lbs

On April 26, 1966, the headline of the morning Oregonian read, “Rifle-Toting Indians Go Fishing.”

Below it was a photo of a Native man, smiling with a 16-pound spring Chinook salmon, while his friend stood guard, one-handing a rifle pointed into the air.

They didn’t have state permits to fish, and they’d been getting harassed by non-Natives at the river and targeted by police. But they didn’t need state permission to fish, they said. They’d had the right since time immemorial, and the treaties said so.

The armed guards, Alvin Settler told the newspaper, seemed to be “the only way we can get justice.”

By the time Randy saw his dad in the paper, he was used to his parents being arrested for fishing. He was about 8 the first time he saw them dragged into a police car, and he cried.

Eventually, he’d get arrested, too.

Sometimes the police would stop by The Dalles Wahtonka High School to see if he was there. If he wasn’t, they knew to search along the river for his family.

More often than not, though, teenage Randy Settler was there in school, frequently asleep during first-period history. He’d spend all night setting nets and the early morning pulling them and trucking the catch over to his mom. When he got to school, he’d slip into the back of the classroom and nod off.

“I didn’t mind sleeping through manifest destiny,” he said.

The Settlers became one of the most aggressive commercial fishing families on the river. Alvin, who’d later become a tribal judge, taught himself the law and began to test the limits of the state’s authority over tribal fishing.

Mary Goudy-Settler and Alvin Settler took such a hard line on treaty rights, and racked up so many fishing violations, that one of the Yakama Nation’s council members tried to distance them from tribal government.

But they were building something.

Goudy-Settler told the Yakama Nation Review at the time that while tribal council was worried they’d jeopardize the tribe’s relationship with the state, “all I could think of was the despair of the Indians.”

July 1978, Summer Chinook/sockeye season

Yearly catch: 1,455,000 lbs

Salmon runs weren’t what they’d been before the dams, but there were still fish to catch, and Goudy-Settler knew how to make the most of it.

With money they’d saved, the Settlers bought property on the river near Stevenson, Washington, about 60 miles east of Portland, Oregon.

They built a home and a building for processing fish. Goudy-Settler started buying and selling salmon from up and down the river to supplement her family’s catch. Eventually, she became one of the biggest fish dealers on the river.

“Some people called themselves ‘fish hogs,’” said Sam George, who has fished for the Settlers since he was a boy and now helps run the family’s crew. “She was a true fish hog. She wanted it.”

She bought boats for Randy and Carl, and they hauled in as much fish as they could. And the Settlers would put kids like George to work cleaning fish or camping by the river late into the night to watch their nets for thieves.

She saw fish dealing as a way to help the tribe, and pulled in money from restaurants as far away as New York.

The police said she was a major salmon poacher. The state wanted to limit the tribes’ catch to protect salmon. The Settlers contended their share was insignificant compared to all the other threats to salmon.

In the summer of 1978, undercover agents from the Oregon State Police posed as buyers, and prosecutors alleged Goudy-Settler had illegally sold $381,000 worth of salmon caught outside the commercial season.

At home awaiting trial, she would lay on her bed for hours with a legal dictionary, trying to decipher case documents. She’d recently learned to read, with the help of her niece and a pile of Cosmopolitan magazines.

She decided to plead guilty, avoiding a public trial she thought she’d have no chance to win.

She was sentenced to 10 months in an Oregon prison. Inside, people kept asking her about her crime.

“What crime?” she’d ask them, according to a 1982 interview in The Columbian.

She and Alvin divorced during her imprisonment. Mary kept the family’s tribally registered fishing sites. Police kept watching.

In 1983, in the parking lot of an undisclosed Portland hotel, undercover police arrested Goudy-Settler and her sons, Carl and Randy Settler, for allegedly selling more than 600 pounds of illegal salmon.

“This fish should be swimming,” a newspaper account quoted an arresting officer as saying while he held one of the seized salmon.

Goudy-Settler was convicted later that year of selling fish without a state license.

Her appeal sat for nearly a decade after her attorney died. In the meantime, she stopped buying and dealing fish, and her family just sold what they could catch.

Settler lost her appeal in 1992, and she was sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Tribal leaders were outraged. Over the years, appreciation had grown for Mary Goudy-Settler and Alvin Settler, and the river tribes honored them for fighting to secure the right to fish for Randy’s generation and beyond.

When Randy took up the mantle, the fight had changed: It became about making sure there were still fish to catch.

November 1997, end of fall Chinook/coho season

Yearly catch: 814,000 lbs

Randy Settler routinely worked from 7 in the morning until midnight during his days on tribal council.

He’d waited a long time to be on it.

He first ran when he was 25. He didn’t get elected till 1997, when he was 42.

Settler had spent much of his youth — when he wasn’t fishing or getting arrested for it — chasing wins at Native basketball tournaments and the good times that came with them.

But he got serious about the fight for salmon.

“Every time I picked up the phone and had a conversation with him, I wound up with six more things I had to do,” Steve Parker, a longtime biologist for the Yakama Nation, recalled.

Settler was outspoken and unconventional. He recalled leaping onto a table during one meeting to make a point. As a negotiating tactic, he said, he once told a National Marine Fisheries Service official that he’d put an “Indian curse” on him. He cut deals to get the tribe funding, even when it meant working with known enemies of Indian Country, like Sen. Slade Gorton, the Washington Republican who as state attorney general had argued against tribal treaty rights and sovereignty.

“A force of nature,” Charles Hudson, the former government affairs director for the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission, said of Settler.

He fought hard because it was a dire time for salmon.

Many populations had cratered to their lowest levels ever in the 1990s. Tribes began the work of resuscitating salmon runs with habitat improvements and hatcheries they’d specially designed to aid wild fish.

Then, in 2001, a major drought hit the Columbia River Basin, reducing the river’s flow and threatening the survival of young salmon making their way to the ocean. Settler feared the greatest die-off for migrating salmon in his lifetime.

During that drought, he argued publicly with the head of the Bonneville Power Administration, the federal seller of hydroelectric power, over its plans to suspend salmon protections to maximize power production.

That marked just one of many disputes over the federal government’s actions toward salmon and tribes. Settler summed up the tribal position in his testimony before Congress at the time.

Fish runs are in terrible condition, he told them: “The United States is not living up to its commitments in the Treaty of 1855.”

April 2022, spring Chinook season

Yearly catch forecast: 3,050,000 lbs

About an hour east of Portland, the Stanley Rock fish camp is a ramshackle collection of boats, trailers and a fish-cleaning station, easily missed from the interstate.

Randy, his nephew Sam George, and George’s daughter Aiyana make this their home for much of the year because Stanley Rock is near where they are allowed to fish, according to tribal law and custom. It’s just the three of them in camp for the spring season, when they catch fish for the tribe’s ceremonies.

“What about school?” Randy teased Aiyana one day.

She looked to her dad. She had skipped school to be fishing that day, just as Randy had done so many times.

“She’s exercising her treaty right,” her dad said.

Settler wonders what will be left to catch in Aiyana’s lifetime.

“When she gets to my age, if she’s sitting in the same place, will she be able to look out on this river and say, ‘Boy, I want my first salmon’? You know, that’s something that I think about,” Settler said.

Sam George is worried too, knowing the water keeps getting warmer. The 2022 run would eventually pick up, and by recent standards it ended up a good year for spring Chinook. But even in good years now, the runs are too small for the tribe to open up a spring commercial season. George has been lining up other work, helping a developer friend build strip malls.

The day after Aiyana skipped school, Settler and George drifted in with the morning’s catch to find her waiting on the dock.

“Good day today! We caught one fish,” George said to her from the boat. “Pull me in.”

Settler headed up the dock and pulled out his phone to call the Yakama tribal council about how to salvage the poor start to the season. It has been 20 years since he served on the council. He’s spent the intervening time working on salmon policy for the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission and the federal Pacific Salmon Commission.

Settler nursed a cigarette and worked the phone, leaning against a plastic storage bin big enough to hold 1,000 pounds of fish. He watched as George tossed that morning’s salmon into the icy slush, and he and Aiyana took a seat on the tailgate.

“I’m surprised we got a fish!” Aiyana said to her father.

“You’re surprised?” he said. “What do you mean you’re surprised?”

“Because this spring we haven’t got any!” she said. ”Are we gonna eat it?”

“No,” he said, “it’s for the longhouse, baby.”

“Aww,” she moaned.

After a while, Settler rummaged through a fresh food box delivery from a local nonprofit. He pulled out a bright orange vacuum-sealed piece of Alaskan sockeye and walked it over to his nephew. George's mother is Settler's cousin, which makes him a nephew in Native terms. With none of their own catch to eat, Settler was eager to cook the salmon for lunch.

“Look how good that looks,” he said, holding up the packaged filet for them to see. “Wild-caught.”

George smiled and shook his head.

“It’s not Native-caught,” he said.

Aiyana laughed at her dad and kicked her legs out over the tailgate. Her pink boots swung back and forth above a license plate commemorating the Yakama Nation Treaty of 1855.

November 2022, offseason

The Celilo Village longhouse filled up by breakfast. People poured in from around the region for the day’s ceremonies.

They came to memorialize Randy Settler’s mother and to hold a naming ceremony for his nephew, George. It is tradition to hold naming ceremonies during memorials. This reflects the life cycle of the salmon, which return to their home streams to die and give life to the next generation.

The ceremony opened with drumming, songs and dance. Then, one by one, members of the tribe began to rise and share stories about Mary Goudy-Settler. They thanked her for the fight.

They talked of the great struggle to come for salmon in the next generation, and of keeping Mary’s warrior spirit alive.

Randy and his sister, Marcella, called upon members of their tribe to come forward and receive a gift in her honor.

When Aiyana’s turn came, they called her forward and handed her a keepsake shawl, necklace and yarn belt of their mother’s.

George’s naming ceremony followed later that afternoon. He was given the name Tookikun, after one of his ancestors. He, too, called members of his tribe forward to exchange gifts: blankets for some, salmon for others, a captain’s mirror for his Uncle Randy. Tribal elders said they gave George a new name to recognize the larger role he’s grown into as a provider of fish for the tribe. He will continue the work of his Uncle Randy to feed the longhouse, and then he, too, will pass it on.

George had said more than once that he didn’t need a name, that he was happy to sit in the back of the ceremony and watch. But he woke up the next day feeling a little different — a good energy.

He’s excited for Aiyana to feel that.

“We have to find her a name,” George said. “She wants hers, too.”