This story was co-published with the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

In the 1990s, Hawaii’s two elder statesmen — U.S. Sens. Daniel Inouye and Daniel Akaka — were at the forefront of efforts to ensure that the U.S. compensated Native Hawaiians for ancestral lands taken from them over the years.

“Dan Inouye believed that a promise made should be a promise kept,” Akaka, a Native Hawaiian, said in 2012 upon the death of his longtime Senate colleague.

But an investigation by the Honolulu Star-Advertiser and ProPublica has found that those same senators voted several times each to support must-pass legislation that included provisions undermining efforts to repay millions of dollars in land debt to Hawaiians. At least six other current and former members of Hawaii’s congressional delegation have supported such legislation one or more times.

Between them, Hawaii’s members of Congress voted for at least six laws authorizing the federal government to sell dozens of excess properties to private parties rather than offering them to a Hawaiian trust established to repatriate the land. In one must-pass military spending bill spanning more than 500 pages, lawmakers slipped in a single sentence that helped a handful of nonprofits to acquire the land. In another, they added language that effectively put the need for military housing ahead of the need for housing Hawaiians.

The circumvention of the landmark 1995 Hawaiian Home Lands Recovery Act, which has not been previously reported, sent the excess lands to a variety of buyers instead: the Catholic Church; the nonprofit operator of a private school; a developer that intends to sell a site to another company with plans to construct hundreds of private-sector homes there.

The transactions mostly involved lands on Oahu, the state’s most populous island, and were executed during a period in which the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, which manages the trust, faced a severe shortage of developable residential land there. About 11,000 Hawaiians are now seeking residential homesteads on Oahu, nearly double what the figure was when the recovery act passed. As the Star-Advertiser and ProPublica reported in December, the trust has only enough land to accommodate less than a third of those homestead-seekers in single-family homes, although it is moving to develop more multi-family housing. Many waitlisters are homeless, and thousands have died without getting a homestead lease.

Even as the federal government was selling excess properties to private buyers, it offered only two parcels to the trust over the past decade, according to the news organizations’ investigation. And one was for a remote mountainside location that DHHL rejected because it determined that the property — a former solar observatory — wasn’t suitable for residential use or to lease for other purposes.

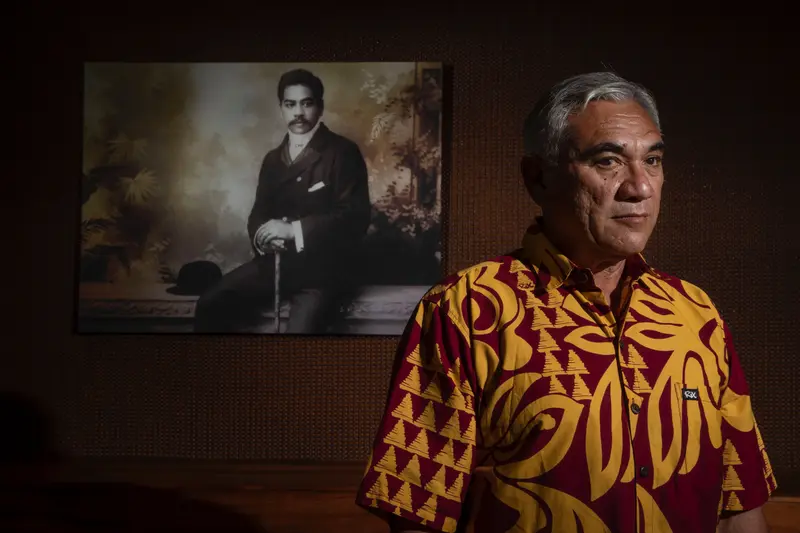

The findings confirmed the suspicions of Mike Kahikina, who said he had a hunch something was amiss during the eight years he served on the Hawaiian Homes Commission, which decides policy for DHHL.

Kahikina joined the commission in 2011, 16 years after the recovery act was signed. Along with eight other commissioners, his job was to help the department get beneficiaries onto residential, ranching and farming homesteads in a timely way — a task DHHL has struggled with historically. By the time he left in 2019, the federal government’s debt was the same size as when he joined.

Kahikina said he periodically raised questions with DHHL about the land debt, but they were never satisfactorily answered.

The news organizations shared their findings with Kahikina — an Air Force veteran, former state legislator, ordained minister and outreach worker for troubled youth — as he sat outside the West Oahu homestead residence that has been in his family for three generations. With his long salt-and-pepper hair tied back in a bun, Kahikina, who now heads the Association of Hawaiians for Homestead Lands, a statewide nonprofit organization of waitlisters, was stunned as he learned details of the private deals. “You connected the dots for me,” he said, repeating himself to emphasize the point. “It’s like we’re an invisible people.”

The investigation relied on federal, state and county records and revealed nearly 40 deals over the past decade involving about 520 acres, all authorized by special language inserted into at least six bills passed by Congress. Beyond the Catholic Church, the developer and the private school operator, the special legislation also allowed land deals with a veterans association, individual homebuyers, another nonprofit private school operator and several religious organizations.

Had it not been for that legislation, advocates say the recovery act could have allowed some of these same entities to access the land while benefiting DHHL at the same time. That’s because under the recovery act, DHHL is permitted to sell certain properties for fair market value and use the proceeds for homestead development.

The Navy, which had owned the majority of lands involved in the private deals, defended its actions. The special legislation expressed the intent of Congress at the time, and if a new law conflicted with a prior one, the new one applied, according to a spokesperson. “Navy followed the law,” she wrote.

The General Services Administration, which plays a key role in federal land disposal, would not address criticisms about bypassing the recovery act. But in response to a letter from one of Hawaii’s two current U.S. senators, a GSA official acknowledged that congressional actions — a reference to the special legislation — allowed some agencies to bypass the recovery act.

William J. Aila Jr., who now heads DHHL and the Hawaiian Homes Commission, said the congressionally approved workarounds deprived the trust of promising development opportunities. “It’s a conscious effort to go around the spirit of the recovery act,” Aila said in an interview. “Somebody had to consciously propose legislation.”

Aila also said that some of the Oahu parcels that were sold would have been especially appealing to the commission because they were relatively flat and already had roads and utility connections. The high costs of installing such systems have contributed to DHHL’s slow pace in developing homesteads in recent years.

“It wasn’t the department that was deprived,” Aila said. “It was the beneficiaries and the people on the waitlist.”

Inouye and Akaka were widely known as strong advocates for Native Hawaiians and were credited with helping secure passage of major legislation benefiting Hawaii’s indigenous people, including the recovery act and bills related to health care and education. But extensive reporting on the special legislation did not turn up evidence that Inouye, Akaka or other legislators publicly addressed the potential impact on the debt.

For their part, Hawaii’s current U.S. senators vowed to stop the practice of workarounds — even though both voted years earlier for legislation allowing it. They said they hadn’t realized at the time that the trust effectively would be left out the loop.

Beneficiaries also said they didn’t know Congress was shortchanging the trust all these years. Many greeted the news with shock. “My heart’s broken,” said Ian Lee Loy, who lives on a Big Island homestead and served on the commission from 2011 to 2013. “The promises to Native Hawaiians continue to go unfilled while the political machine keeps churning and deals are made.”

More Land Still Owed

The circumvention of the recovery act is only the latest chapter in the struggle by Native Hawaiians to reclaim their lands. The U.S. debt to Hawaiians began accruing in the 1890s, after the U.S.-supported overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. In 1898, when the U.S. annexed the island chain, it took possession of 1.8 million uncompensated acres of former kingdom land.

In 1921, as a form of reparation, Congress adopted the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, creating a trust of 203,000 acres from among those taken. In promoting the act, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole, considered the father of the program, referred to the destitute conditions that many families lived in, particularly those in urban tenements.

“That is why the race is fast dying out,” he said in advocating for the bill. “These conditions stare the Hawaiian people in the face.”

The new law authorized the government to issue 99-year land leases to people who are at least 50% Hawaiian for $1 annually.

In the decades that followed, the state and federal governments took control of thousands of those acres for public purposes — roads, airports, schools, military uses — again paying little or no compensation.

The recovery act was specifically meant to compensate for over 1,400 acres the U.S. was using without authorization. Under the act, the trust must be notified whenever most federal land in Hawaii is designated “excess,” or unneeded, by a federal agency. That designation triggers a screening process in which other federal agencies are given an opportunity to claim the land. It also triggers a requirement that the Department of Defense or GSA notify the chair of the Hawaiian Homes Commission of a potential acquisition candidate. If no other federal agency claims the land, the trust has the option to acquire the parcel. If that option is exercised, the land value is deducted from the outstanding debt.

The new law kicked off rounds of negotiations about how to settle that debt. Because not all acres are created equal, the two sides focused on land values and eventually signed a landmark agreement to settle all claims: The federal government would transfer to the trust nine properties totaling 960 acres, roughly comparable in value to the 1,400 acres in question. The land was almost all on Oahu and described in news coverage as prime land.

At a 1998 signing ceremony at the Hawaii governor’s residence, the Royal Hawaiian Band entertained a crowd of VIP guests. The newly inked settlement was hailed as a turning point for the trust.

But things haven’t turned out that way. The trust has not received about 70 acres, including 47 that were removed from the settlement. Two other parcels have yet to be transferred because of a variety of environmental or other complications. DHHL staff last year told the commission that the land debt was worth between $24 million and nearly $34 million in 1998 values, which is how the department tracks the debt. That equates to roughly $39 million to $55 million in today’s dollars.

What’s more, some trust beneficiaries — those who are at least half Hawaiian — believe the homesteading program is due more compensation because of the relatively poor quality of the nearly 900 acres it has received thus far. None of that land has been used for residential homesteads, according to DHHL, mostly due to the location or condition of the property or the prohibitive cost of installing infrastructure. The land is largely being used for industrial purposes.

The federal government did offer, last year, an 80-acre site in Ewa Beach, a former tsunami warning center surrounded by residential neighborhoods and a golf course, along the West Oahu coastline. Hundreds of homes could be developed there, and DHHL said it accepts the offer. If, as expected, the acquisition goes through, the federal government still would owe DHHL more than $11 million worth of land in today’s dollars.

When the Department of the Interior, which oversees the trust for the federal government but doesn’t decide which lands are offered to DHHL, was asked why a balance still remained after 25 years, a spokesman in a December statement gave three reasons. The first was that few excess lands have become available since 2000. The second was that the trust declined several offerings because of contamination or other concerns. And the third? The impact of the congressional workarounds.

Making the Workarounds Explicit

Inouye, a decorated Army veteran who lost his right arm during World War II and went on to become a political legend in Hawaii, was a key figure in winning passage of the recovery act.

But the new reporting shows that he also played a critical role in the creation of the workarounds. One key example came in the 2000s, when nonprofit organizations near Pearl Harbor unsuccessfully tried to purchase the lands they had long been leasing from the Navy. They turned to Inouye for help. By the late 2000s, Inouye was one of the most powerful members of Congress, eventually becoming chair of the influential Appropriations Committee and the Senate’s president pro tempore, third in line for succession to the U.S. presidency. The nonprofits had built churches, schools and other facilities on the land, and they told his staff they wanted to remain.

In interviews, the nonprofits said that after they contacted his office, Inouye in 2009 got language added to the annual military spending bill that enabled the organizations to purchase their leased lands from the Navy for fair market value. Two years later, Inouye added language — a single sentence — to a 566-page spending bill, adding a “clarification of land conveyance” to the 2009 law, specifically exempting those land sales from the recovery act, according to his former chief of staff, Jennifer Sabas.

Sabas said in an email that her memory of how the exemption provision came together was fuzzy, but she recalled several lessees had contacted the senator’s office seeking assistance in acquiring the land. Because they had invested so much in those locations over the decades, “he wanted to provide them the opportunity to stay,” Sabas wrote.

At the time, Sabas added, Inouye believed other nearby Navy parcels would become available and DHHL could pursue those if interested. But no such offers were made to the trust, according to GSA and Navy records. The Navy told the Star-Advertiser and ProPublica that all the lands covered by that special legislation were acquired by the nonprofits.

Through the 2009 and 2011 legislation, six churches, a veterans group and a private school operator purchased more than 20 acres from the Navy between 2013 and 2019, generating roughly $9 million for the federal government, according to public records. That money did not go to the trust.

Several of the nonprofits said they were unaware that the land sales had been exempted from the recovery act until they were contacted recently by the Star-Advertiser and ProPublica.

Bishop Robert Fitzpatrick of the Episcopal Diocese of Hawaii, which acquired its nearly 3-acre site in 2016 thanks to the special legislation, said that had the diocese known that the trust and its beneficiaries were left out of the process, the church would have reconsidered the purchase. He noted that the church was founded in Hawaii in the 1860s with the aid of the monarchy. “Respecting Hawaiian sovereignty is a core value for us,” he said.

Hawaii’s former U.S. Rep. Neil Abercrombie, who voted for the 2009 bill authorizing the land sales, didn’t recall the trust issue being raised at all. “It certainly never occurred to me,” said Abercrombie, who vacated his congressional seat in 2010 to begin a four-year term as governor. “I thought we were doing a good deed.”

In addition to the Inouye efforts, one other bill explicitly included a recovery-act exemption. The military spending measure in 2013 authorized the sale of an 11-acre parcel at Navy Hale Keiki School to its nonprofit operator. The exemption language — inserted into the 494-page National Defense Authorization Act — was a copy of what Inouye had put in the 2011 bill, allowing the Navy to convey title to the land before it is “made available for transfer pursuant to the Hawaiian Home Lands Recovery Act.”

Robin Danner, chair of the Sovereign Council of Hawaiian Homestead Associations, the largest statewide organization representing those eligible for the homesteading program, blamed Hawaii’s congressional delegation and DHHL for the lost opportunities. She pointed out that DHHL basically has two main federal laws to monitor and said its failure to flag the circumventions was glaring. “This would not have happened if DHHL had been doing its job,” she said.

Kahikina, the former commissioner, agreed, saying no one from the agency was aggressively monitoring the situation, enabling the private deals to continue under the radar.

Aila, however, pushed back on this point. He said DHHL doesn’t have the staff to monitor all federal legislation, but that it periodically asked GSA about the availability of property. He also pointed out that the recovery act requires the federal government to notify the trust as excess lands become available.

A More Indirect Route

In addition to the two explicit exemptions, several other pieces of special legislation did not mention the recovery act but had the same end result: The federal government transferred excess lands without offering them to the trust.

Many of those acres were in Kalaeloa, part of the region where DHHL has been concentrating development on Oahu in recent years. Close to a dozen other parcels on Maui and the Big Island were in residential neighborhoods. Critics pointed out that the residential quality of the land represented lost opportunities for the trust’s future housing plans.

Two of the laws benefitted Hunt Cos., a Texas-based developer that has done Hawaii projects for more than a quarter of a century. Legislation that Congress passed in 1999 and 2006 authorized the Navy to sell or lease land on Oahu to pay for redevelopment of Ford Island, a historic Navy base in Pearl Harbor.

Hunt issued a brief statement acknowledging the acquisition of Navy properties but declined to respond to criticisms over the deals.

Alan Murakami, who recently retired as an attorney for the Native Hawaiian Legal Corp., a nonprofit advocacy group, drew on history to criticize the property deals. Given that the Navy never properly owned the Kalaeloa lands, it “had no moral right to treat [them] as a piggy bank,” he said.

Abercrombie, who as a Hawaii congressman and member of the House Armed Services Committee was a key advocate for the 1999 Ford Island legislation, also questioned the Navy’s actions, saying the law was designed to keep all the land in use for military housing. Once the property was placed for sale without maintaining that use, it should have been offered to the trust, Abercrombie added. “It’s crystal clear the Navy had that obligation,” he said.

Asked to respond to the criticisms, the Navy spokesperson said the Ford Island law “speaks for itself.” Quoting from the statute, she noted that it was enacted “for the purpose of developing or facilitating the development of Ford Island.”

“A Slap in the Face”

Just as the workaround deals were picking up momentum, Bode Kalua, 28, a landscaper who is at least half Hawaiian, applied through DHHL for a residential homestead on Oahu. He wanted a place to call home for the family he planned to eventually start. In 2012, DHHL added him to the waitlist, more than 10,000 spaces from the top. Since then, he’s moved up roughly 700 spots, a pace that will keep him waiting for years.

Kalua, now the father of three young kids with a fourth on the way, said the circumventions prolonged the waits for applicants ahead of him. He is renting a home on Oahu’s windward side but, like many other lower-income applicants on the waitlist, he and his family have spent time homeless.

And the private deals were made during a period in which DHHL’s residential awards fell to record lows, hitting single digits in recent years, as the Star-Advertiser and ProPublica reported last year. “It’s even worse than just a broken promise,” Kalua said of the workarounds. “It’s like a slap in the face.”

Sharon Pua Freitas, 55, who applied for an Oahu residential homestead a year after Kalua, shares his disdain.

“It bothers me to my core because that was the land that the United States of America illegally took to begin with,” said Freitas, who is more than 9,000 slots deep on the waitlist and has yet to receive a homestead offer. “Now it’s still in somebody else’s hands.”

Senators Vow Change

Both of Hawaii’s current U.S. senators have voted for legislation to circumvent the recovery act, but they now say they will take steps to ensure the trust isn’t bypassed going forward.

“I won’t defend the circumvention of the recovery act,” Sen. Brian Schatz, chair of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, which deals with Native Hawaiian issues, said in an early March interview. “It’s something that I was just made aware of, and I don’t think it should happen going forward.”

Schatz voted for the 2013 military spending bill that included one of the two explicit recovery act exemptions and allows a sale to the operator of Hale Keiki school near Pearl Harbor. “I will scour every must-pass bill for anything like this to make sure it doesn’t happen again,” he said.

Sen. Mazie Hirono, who voted for the 2011 legislation with the exemption sentence, said she too was unaware of the implications of the measures for DHHL. “It’s clear there’s a gap here that shouldn’t have existed,” she said in an interview.

Prompted by the news organizations’ inquiry, she recently wrote to the heads of the DOD and GSA, the federal agencies required to notify the trust of excess lands, expressing alarm that the state agency wasn’t being properly notified.

A senior Pentagon official wrote back to Hirono, saying his office would review the military’s processes for disposing of property in Hawaii “to ensure each is fully consistent” with the recovery act and the 1998 settlement agreement. He also named a liaison within the department to deal directly with DHHL.

GSA, which did not comment about the news organizations’ findings, told Hirono that the agency would work with the trust to resolve outstanding recovery-act claims — an apparent continuation of the status quo. “As noted in your letter, GSA is aware of specific congressional actions that have also allowed some landholding agencies to bypass the HHLRA to achieve other goals,” Gianelle Rivera, an associate administrator, wrote in her April 19 letter to the senator.

Beneficiaries, lawmakers and others say the best way to prevent the circumvention problem is twofold: Don’t pass legislation allowing that to happen and make sure the federal government notifies DHHL when any excess lands become available.

Agnel Philip contributed reporting.