As he walked along the spongy, damp Louisiana marshland, scrutinizing tracks owned by one of the nation’s largest freight railroad companies, Robert Faaborg was not happy. The strips of wood that held the rails in place, called ties, were rotten. The screws that held them together were rusted. It was the sort of decay that could cause 18,000-ton trains to derail.

That evening in January 2014, the government inspector fired off an email to the two Union Pacific managers who had accompanied him on the ground. He wanted them to picture the death and destruction that could unfold if tanker cars filled with highly flammable Bakken crude oil teetered off the rickety tracks and careened toward nearby homes.

“I was a little surprised that a KEY route with such high volumes of hazardous materials had tie conditions like this,” Faaborg wrote. He asked them to think about the neighboring families they saw that day. “I was struck by a little girl’s voice calling out, ‘Daddy,’” the inspector wrote. “The family of that little girl is counting on us to keep her and them safe.”

Johnny Taylor was clear on what had to happen. As Union Pacific’s manager of track maintenance for a southern swath of the state including Baton Rouge, he knew he “owned” the 120-mile network of tracks and would get blamed for anything that went wrong. He also didn’t want anyone to get hurt on his watch.

Faaborg, who worked for the Federal Railroad Administration, which oversees rail safety, had only been able to inspect some of the tracks. He instructed Taylor to look at the rest and write up defects, setting a schedule to make the whole territory comply with federal code. Until these tracks were brought back to standards, trains couldn’t go 60 miles per hour on them, the inspector said; regulations required Taylor to slow them down. With more substantially damaged tracks, Taylor had 30 days to repair them; if he couldn’t, Taylor would have to shut them down.

As an Army veteran, Taylor respected orders and deadlines and the chain of command. But he sat under his own boss within a corporate structure that prized moving its cargo as quickly as possible. Bakken crude was big business, and that year, as oil production outstripped pipeline capacity, there had been significant increase in shipping crude by rail.

Taylor’s boss, who had been with him during the inspection, gave him a conflicting order, Taylor would later recall in a court deposition and in interviews with ProPublica; the words marked the start of the seven worst years of his life:

If you keep reporting these track defects, you will no longer have a job at Union Pacific.

ProPublica this week detailed a dilemma rail workers face across America. As the nation’s rail companies double down on increasing the speed and frequency of trains to grow their profits, managers at all levels must fulfill that vision and decide if keeping the trains moving requires them to neglect repairs, ignore safety issues and fire those who complain.

ProPublica uncovered 111 instances of workers who claimed in federal court that they had been disciplined or fired for reporting safety concerns like failing brakes and damaged tracks.

In at least three cases in recent years, including one filed by Taylor, juries awarded over $1 million to fired workers. The rail companies quietly settled most of the rest.

But rail workers have gotten the message loud and clear, dozens of them told ProPublica: Their bosses make examples of those who speak up — or, worse, work with regulators to force fixes. As a result, workers said they have struggled with whether to risk their jobs to raise safety issues.

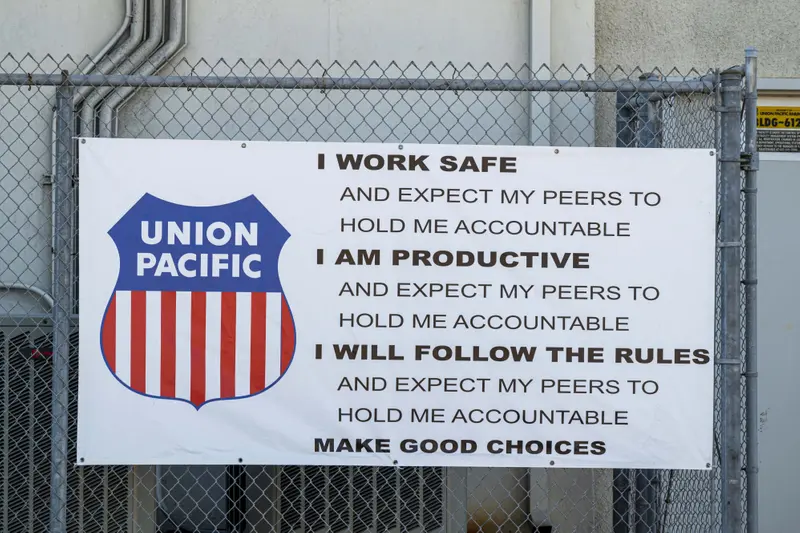

The industry disputes this dynamic. The Association of American Railroads says the rails are safer than they’ve ever been, with accidents on a steady decline. The group attributes this to the care companies take to run safe trains. Union Pacific said safety is its No. 1 priority. “Nothing is more important,” the company said in a written response.

But that is belied by news ProPublica reported in September, when the FRA blasted Union Pacific for running unsafe trains out of its largest yard, in North Platte, Nebraska. According to the agency, company managers pressured inspectors to leave the yard because they were slowing down business.

“That’s basically what they were doing to me,” Taylor told ProPublica. “Now they’ve gotten so bold they are telling FRA inspectors, ‘Don’t come out here.’”

Union Pacific told ProPublica that it wants its employees to report safety issues and work with regulators. In its response to a letter the FRA sent, the company said that it is routine to ask inspectors to move to a different part of the yard if they are in an unsafe location or their work is interrupting train service. Union Pacific said it would address the recent concerns raised by the agency. As for Taylor, the company said his “renditions of the facts vary from those of management.”

Taylor’s former boss, director of track maintenance John Begley, declined to be interviewed about Taylor or comment more broadly. Begley was not deposed, nor did he testify at trial. He has since retired.

This story is based on interviews, sworn testimony and court documents including internal emails filed as evidence.

What happened to Taylor captures in rare detail the impossible position of rail workers who are caught between their bosses and their duty to keep the rails safe, as well as the toll this conflict takes on them and their families.

At 43 years old, with a career that spanned the military, the Mississippi Department of Transportation and seven years at Union Pacific, no one had ever threatened to fire or demote Taylor.

His first instinct was to go to Faaborg; he thought that surely the government inspector would protect him. But Faaborg said there was nothing he could do about an employee’s dispute with a supervisor, according to Taylor. (Faaborg didn’t respond to ProPublica’s attempts to contact him, but the FRA confirmed that it can’t stop the type of intimidation Taylor said was happening.)

Taylor read the Federal Railroad Safety Act, the law that governs conduct on the rails. It protected him, at least on paper; managers couldn’t threaten him for trying to address safety problems. But there was no immediate legal remedy if his bosses retaliated unless he sued the railroad or filed a claim with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. It could take years for the agency to decide a case.

Taylor realized he was alone.

“I made up my mind,” Taylor said. “I’m going to write these defects up. It was the right thing.”

He fixed the problems the inspector had noted and kept flagging more for repair. Sometimes, that required slowing down trains or taking tracks out of service. Even though Begley didn’t make good on his alleged threat to fire him, the blowback kept coming, Taylor said.

He felt it in November 2016, when vice president of engineering Greg Workman asked him whether he was “in bed with the FRA,” Taylor recalled in trial testimony. Workman, who is now retired, denied this during litigation and declined to comment when reached by ProPublica.

And he felt it in March 2017, when he took a troublesome stretch of track out of service after trains kept slipping off the rails. Daniel Jaquess, senior terminal manager, came to the yard to berate Taylor. “Why the fuck did you do that?” he asked Taylor, who turned and walked away. “Where the fuck are you going?”

Recognizing his precarious legal situation, Taylor started lodging complaints about the threats he was receiving with Union Pacific’s ethics hotline and the company’s Equal Employment Opportunity office. In response to the encounter with Jaquess, the company counseled the director on his use of strong language, according to court records. Jaquess declined to comment for this story. In a statement to ProPublica, Union Pacific denied it fosters a culture of intimidation. “We encourage employees to raise concerns and engage in respectful dialogue. We do not tolerate any form of retaliation against an employee making a good faith report of a safety concern.”

The impossibility of his job wore away at Taylor. He used to relax after work, playing the blues or soul on his guitar. But he couldn’t find the notes anymore. He tried to shield his wife from his stress, but Erica Taylor, who had loved him since they were teenagers, knew better.

She felt it as he tossed and turned in bed; she heard it as he talked in his sleep. She couldn’t make out what he was saying but knew it was about the railroad.

Taylor was already struggling when two major forces collided in 2017, ratcheting up the pressure from both sides.

As Bakken production increased, Congress lifted a four-decade ban on exporting crude oil, which started shipping out of Louisiana’s deepwater port in 2017. Competing with other railroads for this uptick in traffic, Union Pacific dispatched new local managers schooled in a business philosophy that was sweeping the industry.

Under precision scheduled railroading, profits soared as companies ran longer and faster trains with quicker turnarounds. The industry’s oil trains, including Union Pacific’s, lengthened, stretching to 100 cars carrying 2.5 million gallons of crude each.

At the same time, Union Pacific was under intense scrutiny about how it handled this cargo. The year before, one of its oil trains derailed outside Mosier, Oregon, spilling 47,000 gallons of crude into the Columbia River Gorge. The tracks there had come loose.

Fed up with Union Pacific’s “failure to maintain tracks to federal standards,” officials at the FRA announced a robust nationwide safety agreement to force it into compliance.

Suddenly regulators started showing up unannounced in Taylor’s region, including a staunch inspector named Nick Roppolo who dropped by weekly. One day, Taylor recalled, the inspector said that if defects weren’t fixed in 30 days, Taylor could face criminal charges under the stricter standards of the safety agreement. Roppolo declined to be interviewed by ProPublica.

As Taylor traversed his vast territory in his company pickup truck, steaming or stressed, he had taken to calling his wife, who would talk to him until he calmed down. But she’d recently had brain surgery to deal with a pituitary tumor and he didn’t want to burden her, so he drove in silence, his mind swimming. Jail? What was this job going to cost him?

Shaking, Taylor pulled over, sat with the engine running and cried.

Taylor noticed how the heavy Bakken crude trains affected the switches, movable rails that shift to guide trains as they transition from one track to another. That fall, two trains derailed in six days at a sequence of antiquated switches.

Taylor, who has degrees in math and engineering, came up with a solution he thought could stop the derailments for good. The switches were too small. The best fix was to replace them with larger ones that could create a softer curve for these longer, heavier trains to navigate.

His local managers didn’t like this plan, which was expensive and would take the tracks out of service for months. Already, Taylor said, one of his new bosses had threatened to take his welding gang after Taylor shut down a mainline track. If Taylor lost control of his crew, it would be harder to fix federal violations within 30 days, which could leave him at fault if the company were fined. Kenneth Stuart, director of track maintenance, denied this in his deposition and said he wanted to use the crew differently. He didn’t respond to ProPublica’s attempts to reach him.

In emails, Taylor and the local managers seemed to be talking past one another. Taylor said he invited them to come see the problem for themselves. Jacob Gilsdorf, general director of engineering for the Southern Division, later testified that he was never asked. Either way, the tracks remained idle. Frustrated by the inaction, Jaquess emailed them all in January 2018, pushing for a plan to get the tracks back: “We have four tracks out of service. … We can’t survive without these tracks. Business is too good.”

Four days later, Taylor restricted train speed on another track for safety reasons. Gilsdorf ordered Taylor to lift the speed restriction, but Taylor refused, thinking of the families who lived less than 500 feet from the defect. Gilsdorf denied this in court testimony and did not respond to ProPublica’s attempt to reach him.

Communications between Taylor, Stuart and Gilsdorf had become tense. One day, Taylor accused them of trying to get him to commit a crime by putting the tracks back in service before they were repaired, according to court records. Another day, he told them he was recording their phone calls and notified them he’d filed an Equal Employment Opportunity complaint, one of many he’d submitted since they came to his subdivision. Stuart claimed Taylor was abruptly hanging up on them, using the catchphrase, “Johnny Out.” Taylor denies this.

Through it all, Taylor was consumed with worry, certain his bosses were working on a way to fire him. He didn’t want his wife to have to go back to work. What would his family do for health insurance? How would he support them? For the first time in his life, Taylor thought about killing himself.

One afternoon that month, January 2018, Taylor and his wife saw railroad bosses in their doorbell camera. They had no idea why the two men were knocking at their front door. Taylor had called in sick that day. He had an appointment with his doctor about his blood pressure, which was spiking from conflicts at work.

When Erica Taylor greeted Stuart and Phillip Hawkins, a family acquaintance who was manager of track projects, she thought Hawkins might be dropping by to see how her husband was doing. But the managers stopped in the foyer.

Stuart announced that Union Pacific was placing Johnny Taylor on administrative leave. He would not be allowed back in the yard, and he needed to turn over company property.

“Bring us the keys. We need the keys to the truck,” Erica Taylor recalled hearing from Stuart. Johnny Taylor went to get the keys and Stuart hollered after him, telling him to bring the company laptop, cellphone and ID card, too.

Erica Taylor started to cry. She couldn’t believe they were doing this at their home, nor could she separate this kind of treatment from the fact that her husband is Black. Coming to their home to emasculate her husband in front of her felt like the kind of thing that would happen in the Jim Crow era. “Look at how they’re making him feel, like nothing,” she thought. “It broke me that they're trying to break this man in front of me.”

Stuart and Hawkins remember this encounter differently. At trial, Hawkins, who is also Black, recalls tensing up when Johnny Taylor walked up behind him, fearing “something was gonna occur.” Hawkins did not respond to ProPublica’s attempt to reach him. Stuart described Taylor’s behavior as “erratic and intimidating.”

As Taylor handed over the artifacts of his 11 years of employment at Union Pacific, at last he could express his frustration with the way it ran its railroad. “Get out of my house,” he told the men.

He knew this was the first step in firing him despite years of positive evaluations. In his most recent review, the division supervisor wrote: “Thank you is not enough. Your leadership and dedication are a huge part of this service unit’s success.”

His instincts were right. His bosses had started the paperwork, claiming to the personnel office: “Taylor has decided he doesn’t have to do anything his manager or director tells him to do. He claims he is being retaliated against every time someone assigns him a task.”

They soon presented Taylor with a three-month performance improvement plan that described him as “disrespectful and insubordinate” and “argumentative.”

When Taylor refused to sign it, he was fired.

Five days later, he received a $15,000 bonus check, the largest he’d ever earned, for his good performance at Union Pacific, commending his crew’s injury-free days, how he stayed under budget and how he managed traffic on damaged tracks, while noting he needed to have a more positive attitude.

Taylor’s bonus disappeared quickly as he tried for more than a year to find a job. The mailbox was full of notices from bill collectors; and they kept calling, threatening to repossess his boat, an easy-to-afford luxury when he was making more than $100,000 a year. But he wasn’t in the mood for recreation.

“I’ve seen my husband sad before, but I’ve never seen my husband depressed to the point where he’d just sit in the dark,” Erica Taylor recalled. “His demeanor was just like they took that military arch out of his back.”

For months, he wore the same stained sweatpants as he filled out a spreadsheet of more than 100 rejected applications to jobs that ranged from a Texas engineering company to the local Home Depot. His decade of experience maintaining the tracks wasn’t easily transferable. And he had to tell the truth about how he got fired, making companies suspect he was a troublemaker.

Taylor decided he wanted to teach middle school science; it took a year to qualify for a teaching certificate. When he did, his wife knew how to mark that moment. “That particular pair of jogging pants, I ended up throwing them away,” she said.

Taylor filed suit against Union Pacific in December 2018. Last year, a jury agreed with his version of the story. After a short deliberation, it delivered him more than $1 million for wrongful termination; Union Pacific was ordered to pay his attorney’s fees.

Taylor kept his composure until he left the courtroom. Then, he wept. All this time, he’d been made to feel he’d done something wrong. He felt vindicated. “The jury said yes, I was right. I did the right thing.”

The managers who had conflict with Taylor — Jaquess, Stuart and Gilsdorf — remained at Union Pacific.

Officials with the FRA told ProPublica they forwarded Taylor’s claims onto the Department of Transportation’s Office of Inspector General, something the agency says it does when it believes there is potentially something criminal in a case. When ProPublica asked the Office of Inspector General about the referral, it replied with “no comment,” a response it typically gives when a case is still pending. Union Pacific said it was unaware of this development and is reviewing.

Taylor now teaches engineering and robotics. He loves working with his sixth, seventh and eighth graders and takes far less blood pressure medicine.

But he still thinks about the families who live near the tracks and scans the news for derailments. He worries about how Union Pacific is managing his old territory. “I’m very concerned that they’re not doing a good job protecting those tracks,” he said.

Gabriel Sandoval and Dan Schwartz contributed research.