The very richest Americans win at the tax game no matter which measure you use. ProPublica has published an article, based on a vast trove of never-before-seen IRS information, that reveals the pittance in taxes the ultrawealthy pay compared with their massive wealth accumulation.

But that trove of IRS data also reveals new information on how little the 25 wealthiest Americans pay in taxes by the most conventional measure: income. Not all are able to minimize their income and avoid taxes; some report very substantial sums. But even then, the data — and a new analysis by ProPublica — shows they still pay strikingly low rates.

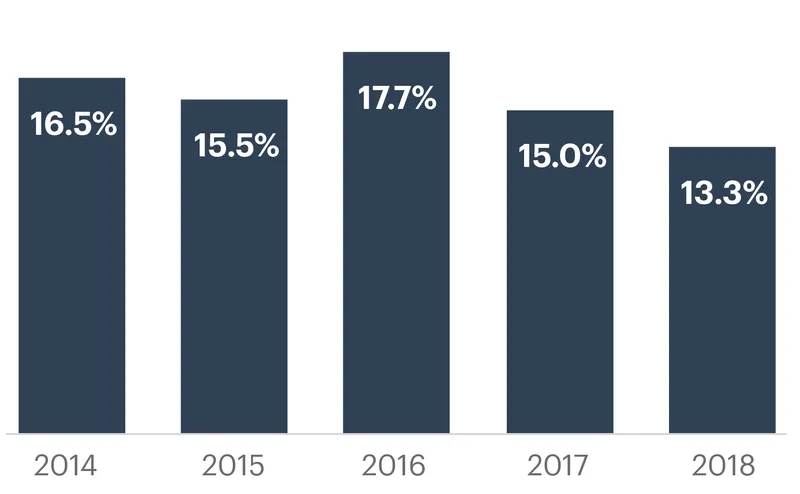

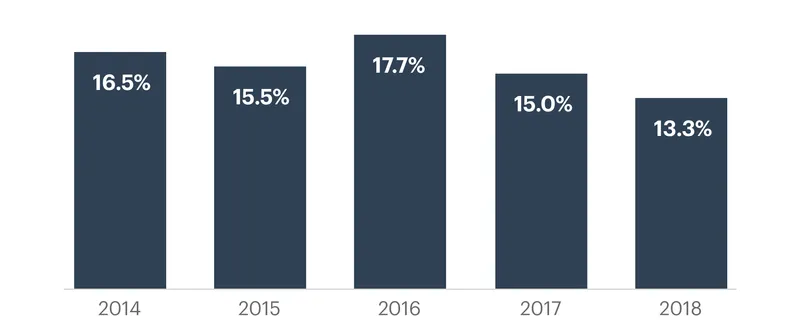

On average, they paid 15.8% in personal federal income taxes between 2014 and 2018. They had $86 billion in adjusted gross income and paid $13.6 billion in income taxes in that period.

That’s lower than the rate a single worker making $45,000 a year might pay if you include Medicare and Social Security taxes.

Even by the Most Conventional Yardstick, the Ultrawealthy Pay Low Income Tax Rates

The top tax bracket is 37%, but the 25 richest Americans paid an average of 15.8% on their reported income from 2014 to 2018.

The federal tax system is designed to be progressive: The more money people make, the higher the tax rate they’re supposed to pay. Today, a married couple pays a tax rate of 10% on their first $19,900 in taxable income (after deductions), stepping up to 37% for everything they make above $628,300.

But those are just the rates on paper. To get a more accurate picture, analysts at the IRS look at what taxes people actually pay. This is known as the “effective tax rate.” If you made $10 million, and paid $2.5 million in taxes, you’d have had an effective rate of 25%.

Looking strictly at income taxes, IRS statistics show that effective tax rates do, in fact, climb with income. In 2018, the latest year for which data is available, those earning between $500,000 and $1 million paid a tax rate twice as high, on average, when compared with taxpayers earning between $100,000 and $200,000. Taxpayers earning between $2 million and $5 million paid 27.5%, the highest of all taxpayers. But, at that point, the climb stops.

From there, rates descend as incomes rise. By the time you reach the most rarefied income grouping whose data is released by the IRS — the top .001% of taxpayers, a collection of 1,400 who each disclosed income over $69 million — the rate has fallen to 23%.

But as ProPublica’s new analysis shows, the top 25 pay even less than that.

How is that possible?

Generally, the wealthy of all stripes keep their tax rates low in multiple ways. Some are simple: They avoid forms of income, like wages, that are taxed at a high rate, 37%, and instead make most of their money via capital gains and dividends from investments, most of which is taxed at 20%. (Among those with the highest annual incomes and the highest capital gains are the managers of elite hedge funds.) Large charitable donations reduce taxable income. Other tax-saving approaches are more arcane: everything from taking deductions for things like interest payments to various credits for business owners.

The top 25 take these strategies and apply them on an epic scale, ProPublica found. The richest also can choose when to take income, matching up their deductions to reduce their bills. Using their vast holdings of stock, they can make large charitable grants. This achieves the twin feat of avoiding any tax on the stock’s growth while getting tax deductions for the full value.

To grasp how low the personal tax burden of the country’s richest Americans is compared with typical wage earners, you also need to count other forms of federal taxes. Social Security and Medicare obligations, which are automatically withheld from paychecks for employees, hardly hit the ultrawealthy at all, because they tend to avoid the forms of income, like salaries, to which the taxes apply. ProPublica found that such taxes had a negligible effect on the total burden of the top 25. If we include them in our calculation above, it would raise the average tax rate of the wealthiest from 15.8% to 16%.

Most workers, however, pay more in Social Security and Medicare levies than in income taxes — though they probably don’t know it. Taxes for these retirement and health programs are administered in a way that makes them almost invisible: Not only are they subtracted automatically each pay period, but the burden is split. Half is taken directly from employees’ pay and the other half is paid by employers.

Take the typical worker we cited above, who had a salary of $45,000 in 2018. With the standard deduction, this worker’s income tax bill would be $3,800, a rate of 8%. But now add payroll taxes. The worker paid a bit more than $3,400 directly over the course of the year; in addition, the worker’s employer paid an equivalent amount as their share of the worker’s Social Security and Medicare taxes. Government agencies and most economists typically count both contributions — a total of nearly $6,900 in this instance — as a tax that is effectively borne by workers since it’s part of the cost of paying their wages. The logic is that employers consider those costs when hiring and would hire fewer people or pay them less because of the tax burden.

All in, our worker paid $10,700 in taxes. Taken as a percentage of the worker’s full compensation (including a typical health plan), this comes out to a rate of 19%.

Yes, that’s higher than the average rate of the richest 25 Americans.